As the surge in monkeypox and another Covid-19 variant continue to dominate headlines, another public health threat quietly looms – one that particularly affects women as they age and has worsened considerably during the pandemic – loneliness.

Yes, that’s right. Loneliness is becoming a public health emergency, so much so that countries like Japan and the United Kingdom have appointed Ministries of Loneliness to tackle the problem in recent years.

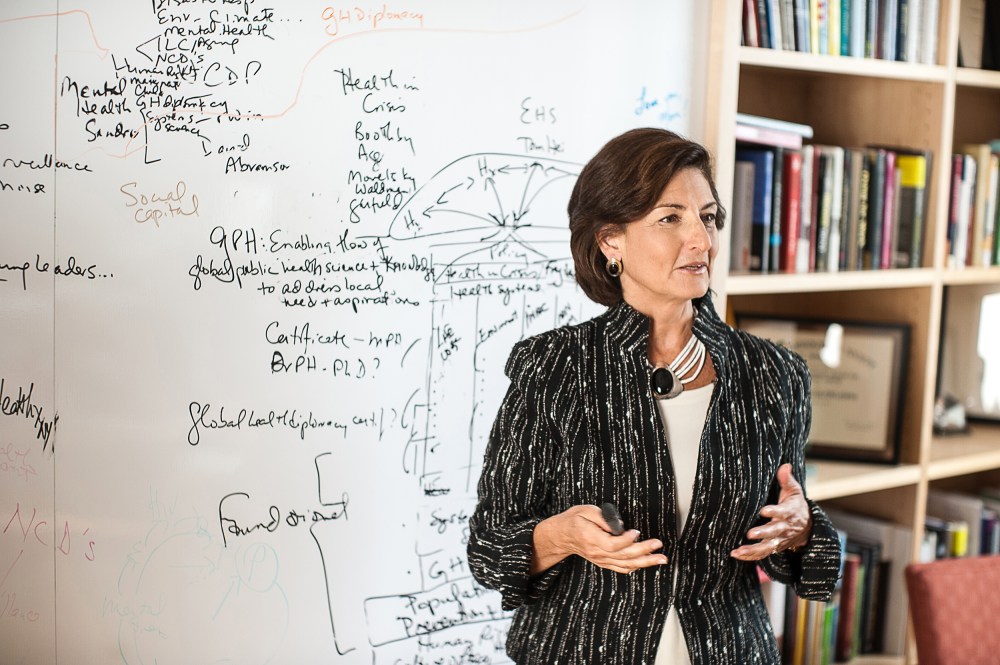

As a medical doctor and public health expert who has spent decades as a geriatrician caring for older adults, and a scientist studying the factors that create health and wellbeing in aging women versus men, we need to pay attention.

By 2035, older adults (65 and up) will outnumber children for the first time in U.S. history, which means that we will have a larger generation of older women than ever before. This seismic demographic shift will create a new cohort of women who will be uniquely vulnerable to loneliness and its health hazards.

While perceptions of loneliness may vary – home alone on a Saturday night, holidays without social activities, empty nests and widowhood – ample evidence shows that loneliness and social isolation are, in fact, public health emergencies with profound and deadly consequences to our bodies and our society.

Clinically, loneliness is defined as a subjective feeling of pain due to unmet needs for meaningful, satisfying connections to other people, creating a distressing gap between actual and desired relationships.

Social isolation is a measure of social interactions and being physically separated from other people, as many of us experienced during the pandemic.

Chronic loneliness and isolation, independent of each other, can harm both mental and physical health, contributing to conditions such as obesity, inactivity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, anxiety and poor sleep, which increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke, especially for older women.

According to a recent study led by researchers at the University of California-San Diego, postmenopausal women who reported high levels of social isolation and loneliness had a nearly 30 percent increased risk for heart disease compared to women who reported low levels of social isolation and loneliness.

The National Academy of Medicine’s “Global Roadmap for Healthy Longevity,” a new commission I co-chaired, examined the worldwide implications of loneliness and called for large-scale approaches across all sectors. This epidemic is global and growing, with women 65 and older experiencing increased isolation and a more acute sense of relational loneliness – the lack of quality friendships and family connections – than their male counterparts.

While all older adults are at an increased risk of both conditions as their social networks shrink – whether it’s due to loss of family and friends, or not being near them, having no children, being single, divorced, retired, or having fewer activities related to daily living – evidence shows that women will suffer the most severe consequences.

For one, they live longer than men and are less likely to have a partner. That’s compounded by the shrinking of their social network, a greater likelihood of living alone for more years, and a greater risk of poverty in old age, compared to men.