I remember when “The Greatest Show on Earth” came to Hunting Park. It really happened. I Googled it. In 1950, the Barnum & Bailey Circus really did come to Philadelphia. It’s in the books.

Better yet, it’s all in my head. I remember the day Dad and Mom took us across from where we lived in that tiny second-floor apartment above the Italian grocery at Hunting Park Avenue and Broad Street. They did it twice: in the afternoon to walk along the gangway and see the lions and tigers in their cages, and that night to the center ring to see all those clowns come climbing out of that little car.

What’s truly wondrous is that Hunting Park is where we and everyone else in the neighborhood hung out. We’d go there on a summer evening to stroll among the old gazebo, the merry-go-round, and the stand where they sold those cartons of orange drink that afterward you could turn into actual cardboard megaphones.

RELATED: Pope Francis holds mass in Philadelphia

All this was in those years our parents forever called “after the war,” as opposed to “before the war.” Or as Dad’s mom, Grandmom-in-Chestnut Hill, would always say when speaking of the distant past, “Oh, that was years and years ago.”

It was a great neighborhood back then. Grandmom and Grandpop Shields, Mom’s parents, lived around the corner from us on 15th Street. Everyone walked everywhere, including to the grand St. Stephen’s Church a few blocks down on Broad Street. To let you know how different things were, you couldn’t miss the big trough at the corner of Hunting Park and Broad where the horses that delivered our milk and collected the trash drank and splashed away.

Yes, that was “years and years ago.” It seems, looking back from 2015, as though that time was a lot closer to the 1800s than it was to today. In fact, it was. Do the math.

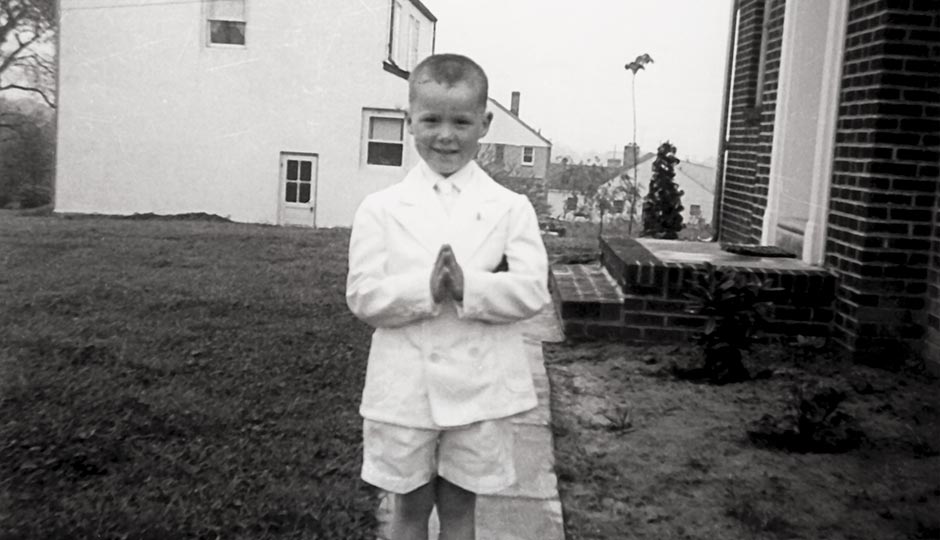

Though I doubt the words would have meant much to me at the time, we lived in a totally Catholic world — Irish Catholic. Mass at St. Stephen’s was definite old-church. You dressed up. Everybody did, especially the adults. Grandpop always put on his three-piece gray suit. It was all in Latin, and the priest stood with his back to us just like it showed in those stages of the Mass in the missal. The altar boys rang the bells more often than they do now. And people came on time. I remember once when Grandpop took us and we were maybe five minutes late. When Mass was over, he sent me and my older brother Herb — we called him Bert back then — home, while he stayed for the entire next Mass. He was like that. It was like that back then.

Ours was a religious family, round-the-clock religious. There were crucifixes in Grandmom and Grandpop’s house, and framed devotions to the Sacred Heart on the dining room wall. Grandmom was always talking about a “novena” that was about to be celebrated. When she got upset at something, she had a standard response: “Jesus, Mary and Joseph!” was both her prayer and her sigh at having kids forever around. One of her daughters, Eleanor, had joined the Sisters of St. Joseph at a young age and was already teaching what we call “special education.” Today, at 92, Eleanor is at St. Joseph Villa in Flourtown. I pray she gets to read this.

Auntie Agnes would also become a nun, but in the years when we were just becoming aware of things, she was going to school up at Mount St. Joseph’s. Her bedroom was in the front of the house on 15th Street. It was the nicest room, catching the sun and filled with her girl stuff, her field hockey stick, her perfectly kept marble-backed copybooks. The room smelled of talcum powder or something else wonderfully girly. I once dreamt of being in that room with the Devil talking to me. I can’t remember what he was saying, only the slow, commanding, menacing voice. It didn’t seem like a dream, not then, not in memory. It seemed real.

RELATED: Pope Francis to immigrants: ‘Never be ashamed of your traditions’

Aunt Agnes was still a teenager back then and therefore the coolest possible person to hang out with. She would take us to movies down on Broad Street and to a malt shop afterward. Her decision to give up a scholarship to Chestnut Hill College so another girl could have it — one who wasn’t becoming a nun — is part of our family story.

As religious as she was, Grandmom was stricken when she learned that a second daughter was heading to the convent: “Wait till your father hears it!” But the funny thing was Grandpop’s acceptance: “Whatever makes you happy,” he told his youngest. Agnes would for many years chair the Chestnut Hill College English department.

As I said, at the rowhouse on 15th Street and in our world near Hunting Park, it was all about the Church. I remember the morning Cardinal Dougherty had his funeral. It was on television the whole morning. The year was 1951. I was five years old. What’s amazing is that the great man had been archbishop of Philadelphia since 1918. It was as if he’d always been the Church’s leader. The treatment by local TV was appropriately reverential. The Mass at Sts. Peter and Paul was like an event at the Vatican. Or it certainly seemed that way at Grandmom’s.

Did I mention we were Irish? Grandmom’s maiden name was Conroy; her mother’s was Quinlan. Call it vanity, but I took great pride when my cousins agreed several years ago that I was “a Quinlan.”

Anyway, there were aspects of our lives that I now definitely connect with the country we all came from. One was what we ate and how we did so. My brother Bert and I would spend many a morning on Grandmom’s porch, watching the horses pull the milk wagon up 15th Street. Bert was the one who noticed how the horses always knew which rowhouses to stop at. The afternoons were just as memorable. We’d sit on the davenport, helping Grandmom make dinner. We’d get started about three, just when the Hunting Park outbound traffic began. Before us were the vegetables Grandmom had gotten for “Daddy’s supper.” Everything was from scratch: no cans, and frozen food hadn’t come along yet. We’d shell the peas, husk the corn, clip the string beans. Grandmom would then take it into the kitchen in the back and boil it all for two to three hours. Okay, I’m exaggerating, but the Irish know what I’m talking about.

Grandpop! Charles Patrick Shields was a character straight from Eugene O’Neill. (For a particular reference, see A Touch of the Poet.) He worked as a supervisor at a plant several subway stops away. He’d head off to work in his peacoat and cap, carrying his lunch bucket and Thermos. He could have been a guy making his way to his job in County Cork.

His true position, the one he kept in his head, was that of a greater man altogether. There’d been money in the family. A couple generations earlier, the Shieldses had owned the local dairy. Even when we were growing up, Grandpop would wear his three-piece suit all day on Sunday as a sign of his better station.

The Depression had been hard across the board. Family legend told how Grandmom pinched pennies and Grandpop walked the nine miles to and from City Hall every day of the week, looking for work. Only years later did I realize he’d been hoping to pick up a patronage job from the old Republican political machine, which dominated Philadelphia for 87 years.

%22Years%20later%2C%20Mom%20would%20ask%20a%20friend%20of%20mine%20during%20a%20wildly%20uphill%20Democratic%20primary%20campaign%20I%20was%20running%20for%20Congress%2C%20%27Do%20you%20think%20he%E2%80%99s%20just%20a%20dreamer%2C%20like%20my%20father%3F%27%20Talk%20about%20growing%20up%20Irish%20Catholic.%22′

Beginning in the early 1950s, all this changed — the city’s and Grandpop’s politics both. He was now a proud Democratic committeeman, leading, he would brag, “the best division in the city.” This was when the neighborhood, and 15th Street itself, began to change, with all those reliable African-American votes arriving under his political watch.

Switching parties was just what a lot of the Irish did back when the Republicans were dying and the Democrats, buoyed by FDR, were coming into their own. It was politics itself that Grandpop loved, and that I loved to talk with him about. He always kept up his personal notion of being a man of a certain distinction. As we grew up and visited, often staying overnight, my brother Bert and I would join him on his long walks through Nicetown and Tioga. After supper, he’d head off with his Phillies cigar lit. On his way home, he’d stop at the newsstand on the corner of Broad and Hunting Park and get the bulldog edition of the Inquirer, then sit reading it under the mantelpiece in the living room. Afterward he’d look up, smile, and repeat those grand words of recognition: “Christopher John.” Honestly, can you beat that?

Years later, Mom would ask a friend of mine during a wildly uphill Democratic primary campaign I was running for Congress, “Do you think he’s just a dreamer, like my father?” Talk about growing up Irish Catholic.

She later broke loose in a bigger way. She married a Protestant.

Dad had grown up in Chestnut Hill. His mom, our Grandmom-in-Chestnut Hill, was an Orangewoman of the first order. She had come to America from Northern Ireland early in the century to work for the rich, and married an English chauffeur who did the same. Tall and strong in bearing, she grandly survived Grandpop’s early death in the 1950s and ran a laundry business out of her house. Her accent and stout character were pure Mrs. Doubtfire.

Mom had her unique way of accounting for the religious difference between the two families — this matter of her engaging in a “mixed marriage.” First, she got Dad to convert, arguing the wrongness of Calvinism (another family story). While Dad was raised Episcopalian — Church of England — Grandmom-in-Chestnut Hill was an upstanding member of the estimable Presbyterian church right there on Germantown Avenue. Somehow we divined that Mom had made a strong, relentless charge against the un-American-ness of predestination, working on Dad’s deep Republican faith in self-reliance.

Dad’s conversion was apparently not enough. Mom still felt the need to account for Grandmom-in-Chestnut Hill. I remember the time it came to a head. As was the custom, Bert and I were staying at Grandmom’s while Dad and Mom were on a week’s vacation. (They always took us on a second one).

“Mom says the reason you’re Presbyterian,” one of us said, “is that there wasn’t a Catholic church when you moved to Chestnut Hill.” Grandmom’s response was brisk, clear and final, rejecting the heresy she’d just heard out of hand: “I’m a Presbyterian,” she said, slow, sure, and generously defiant. “I’ve always been a Presbyterian.”

The wondrous thing is how all this worked together, these separate worlds of grandparents, the rowhouse people in North Philadelphia, the Protestant Irish grandmother in Chestnut Hill, worlds overlapping to love the fortunate five sons — Bruce and Charlie and Jim were soon to come — of Herb and Mary Matthews.

Grandpop called it “God’s country.” It was the acre of property Dad and Mom bought on Southampton Road to be their new world. We’d been cooped up too long in that tiny apartment on Hunting Park. Like other young couples after the war, our parents were making their break for it, in their case to that fine hamlet of Somerton, right next to Bucks County.

There weren’t many Catholics up there. Our neighbors on either side on Southampton Road were Protestant. Our other neighbors were the cows out back and the five farmhouses that surrounded us.

Mom took a certain pride in the fact that we were “among the first 25 families” in what was about to be the new parish of St. Christopher’s. But when we arrived, it was still a mission church up there: St. Edward’s. For school, we had to take a long school-bus ride down to Bustleton, to Maternity of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Maternity was the perfect name for what was coming. Our first grade of baby boomers had a hundred kids in it. It was so big they had to put us in the auditorium.

By third grade, we were headed for the new school up in Somerton, on Proctor Road. Father Purcell, the first pastor, was also the first person I ever met named liked me, Christopher. I assume it’s how the new parish got its name. Certainly, Father had a good deal of power. The school, at his direction, was built entirely on a single floor, much like the motels that were springing up across the country. Concerned about fire, he — or someone — designed all the classrooms to have their own doors opening to the outside.

%22Every%20kid%20knew%20that%20his%20parents%20were%20much%20tougher%20than%20the%20Sisters%20of%20Mercy.%20They%20were%20always%20on%20the%20side%20of%20the%20Sister%2C%20always%20ready%20to%20add%20to%20any%20punishment%20she%20decreed.%22′

A lot happened that year I was in third grade at St. Christopher’s. Part of it was inherited ritual, starting with the teasing among the grades: “First-grade babies, second-grade brats, third-grade angels … ”