Tasha Kaminsky, a director of development at a non-profit organization in St. Louis, would love to have children. In many ways, the timing could not be better. Kaminsky, 33, is happily married, has a stable job and owns a home. Standing in the way, however, is one major obstacle: her student loan debt.

It’s been 10 years since Kaminsky took out a $75,000 federal loan for graduate school, and she has never missed a payment. Before the pandemic-era pause on federal loan repayments took effect in March 2020, between $250 to $500 of her salary went towards paying off her debt every month. After a decade of payments, Tasha still owes $107,411.

“I genuinely think I will just die in debt,” Kaminsky told Know Your Value.

While President Joe Biden considers taking action to forgive some federal student loans, the federal moratorium on student loan payments is set to expire in August. Once it does, affording child care – an average $10,041 per year in Missouri – in addition to Kaminsky’s student loan debt has made the idea of starting a family even more daunting. “We can either continue to live comfortably, or we can live on a shoestring budget because of the student loans,” she said.

Kaminsky is far from alone. Nadia Yusuf, a 28-year-old attorney in New York City, said she would move to a job with a better work-life balance for less pay were it not for her student loans. Another New York attorney, Tochi (who declined to publicly share her full name out of concern of offending her employer), said she would pursue a career in domestic violence law if her loans were less expensive.

“How am I supposed to accumulate wealth for myself to venture out on my own or do something different?” Yusuf wondered.

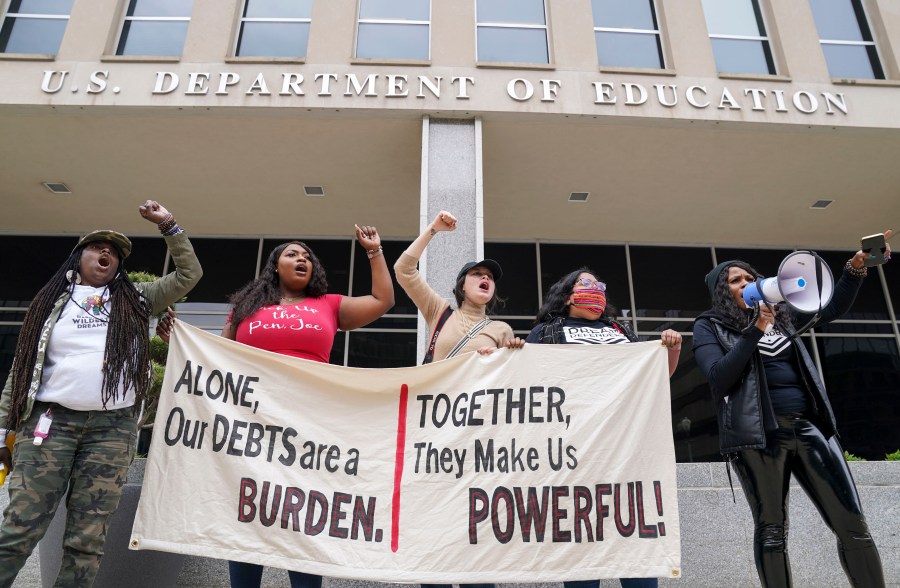

Of the 45 million Americans owing a total of $1.7 trillion in federal and private student loans, two-thirds are women. Women of color are particularly hard hit, a situation exacerbated by a racialized and gendered wage gap.

According to a recent CNBC and Momentive survey, Black and Hispanic women are twice as likely as their male counterparts to have student debt.

And, the racial gap in student loan debt has grown over the last 20 years. Between 2000 and 2018, the median student debt for white borrowers went from $12,000 to $23,000. For Black borrowers, it has gone up from $7,000 to $30,000, according to an analysis from the Roosevelt Institute. Black women, on average, owe $41,466.

“Student loan debt for many is now untenable,” said Dr. Nicole Smith, chief economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “Are student loans an investment in human capital? Absolutely. But should we pay for this investment 10, 20, even 30 years after graduation?”

She added that for many Black women, trying to pay off student loans is “like running against the wind.”

That’s exactly how Joella Jones, a 33-year-old litigation attorney, feels. Jones said she would be able to save enough money to buy a house were it not for her student loans.

Growing up in Denver, Colorado, Jones, never imagined earning as much money as she currently does now in New York City. Her father and uncle grew up in poverty and became the first in their family to attend college. After earning his doctoral degree, her father became a professor at the University of Denver — serving as a beacon of the kind of mobility made possible by higher education.

So, when Jones graduated from Columbia Law School and started at a high-paying firm last year, she felt like she’d struck gold. But the reality of repaying her student loans soon kicked in. Jones currently owes $363,066 in federal loans for her law, master’s, and undergraduate degrees. Not to mention, she and her husband have another mouth to feed with the birth of their baby boy, Abraham, in April of last year.

They hoped to purchase a house so Abraham could have more space than their current one-bedroom apartment. But when the pause on loan payments ends this summer, Jones anticipated having to contribute $3,000 a month towards her loans, pulling her dream of buying a home further away.

“It feels really crushing,” Jones said.

Many mothers with student loan debt face the same dilemma. According to a study by the American Association of University Women, women spend an average $920 per month on housing, $396 on car loans or leases, and $307 on student loans. For the 16 percent who are mothers, an additional $520 goes towards childcare every month – leaving them with a monthly deficit of $372.

Dr. Richelle Brooks, a K-12 principal and founder of ReTHINK It, an organization dedicated to addressing systemic racism in education, also feels this deficit.

Once the pause on loan payments ends in a few months, Dr. Brooks will need to contribute $598 a month towards her $240,000 student debt through an income-repayment plan. As a single mother of two, she does not see this as an option. “I am in the hole each month. Where is that $598 going to come from?” she said.

As the co-founder of the Los Angeles chapter of The Debt Collective, a national union of debtors, Dr. Brooks advocates for full student loan cancellation as a means for economic justice. “I’d even go so far as to say that indebtedness is Jim Crow 2.0,” she said.