In the historical context, the United States of America is still young. Yet even though we don’t have as long a history as say the Italians, Chinese, or English, we have racked up an impressive list of historically important people. George Washington fought to help form this country while Abraham Lincoln fought to keep it together. Ben Franklin lit up the night sky with his kite and some lightning, while Thomas Edison brightened our homes with his light bulbs.

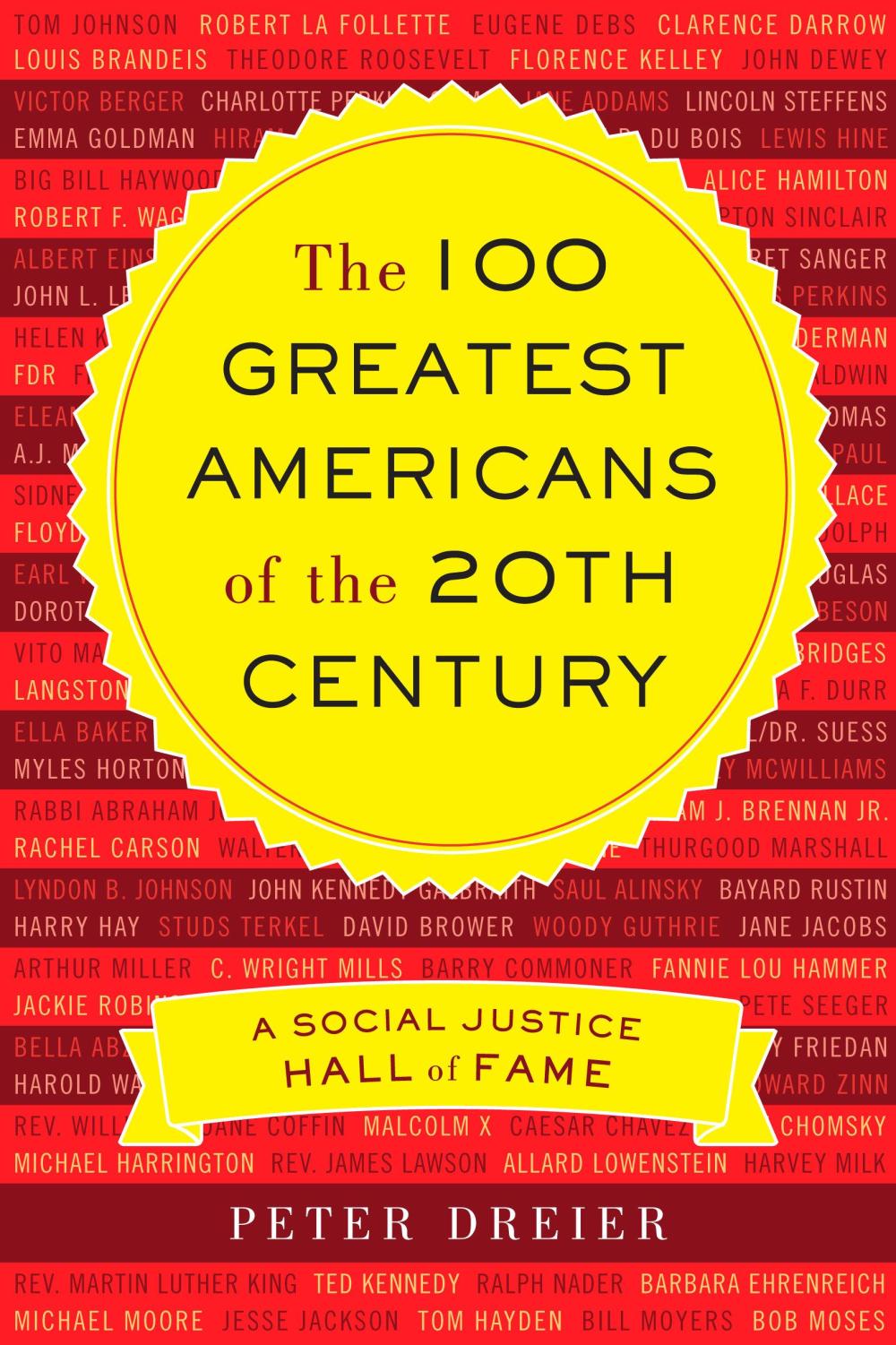

In the new book “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th century” author Peter Dreier takes a look at the people who helped shaped the political, social, and technological landscape of the past century and today. He breaks the individuals on his list up into 3 categories: Activists, Thinkers, and Politicians. “Each generation of Americans faces a different set of economic, political, and social conditions,” says Dreier “Unless we know this history, we will have little understanding of how far we have come, how we got here, and how progress was made by the moral convictions and courage of the greatest Americans.”

Some of the people on Dreier’s list will come as no surprise. Martin Luther King Jr, Albert Einstein, and Jackie Robinson were all leaders in their fields. Yet, some might surprise you, Bruce Springsteen, Michael Moore, and Ted Kennedy, but not his brother John. Take a look at the full list here.

Who do you think should have made the list? Who should have been left off? Find out who the Cyclists are surprised is and isn’t on the list. And from looking back at our history hear Peter Dreier’s take on the current political landscape. As the American philosopher George Santayana said, “Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. “

Check out an excerpt from the book below and be sure to tune in for the full conversation today at 3:40pm.

Excerpted with permission from The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame, by Peter Dreier. Available from Nation Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2012.

Margaret Sanger

(1879–1966)

WHEN FEDERAL agents arrived at Margaret Sanger’s home with a warrant for her arrest in 1914, she calmly ushered the men into her cluttered living room and quietly spent the next three hours explaining why she had mounted a campaign to promote birth con- trol, especially to women of little means. She had been indicted by a grand jury on nine counts of breaking federal laws against distribution of birth control information with her newsletter the Woman Rebel. The

potential prison sentence was forty-five years. By the time Sanger completed her persuasive argument, the agents agreed with her. Nevertheless, they said she had broken the law, and they had no power to rescind the warrant.

Throughout her life, Margaret Sanger ran afoul of the law in her quest to promote women’s health and birth control.

Born Margaret Higgins, she was the sixth of eleven children in a working- class family in Corning, New York. Her father, Michael Higgins, a stonemason, was a freethinking atheist who gave Margaret books about strong women and encouraged her idealism. Her mother, Ann, was a devout Catholic and the strong and loving mainstay of the family. When her mother died from tubercu- losis at age fifty, Sanger had to take care of the family. She always believed her mother’s many pregnancies had contributed to her early death.

Sanger longed to be a physician, but she was unable to pay for medical school. She enrolled in nursing school in White Plains, New York, and as part of her maternity training delivered many babies—unassisted—in at-home births. Some of the women had had several children and were desperate to avoid future pregnancies. Sanger had no idea what to tell them.

Soon after her 1902 marriage to architect and would-be painter William Sanger, she became pregnant, developed tuberculosis, and had a very difficult birth, followed by a lengthy illness and recovery. The young family moved from New York City to the suburbs for Margaret’s health, but two babies and eight years later, Sanger insisted that they return to the city.

In the city the Sangers were part of a left-wing circle that included John Reed, William “Big Bill” Haywood, Lincoln Steffens, and Emma Goldman. Goldman had been smuggling contraceptive devices into the United States from

France since at least 1900 and greatly influenced Sanger’s thinking. Sanger joined the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World, providing support for its strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 and in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1913. Sanger also returned to nursing, working as a visiting nurse and midwife at Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement in the Lower East Side. Again, women repeatedly asked her how to prevent future pregnancies. In those days poor women tried a range of quack medicines and dangerous methods to end pregnancies, including knitting needles. A turning point for Sanger came when one of her patients died from a self-induced abortion. Sanger decided her life’s mission would be fighting for the right of low-income women to control their destinies and improve their health through family planning.

The Sangers went to France, which was then, with regard to contraception, the most progressive nation. After learning as much as she could from the French, she returned to the United States and launched her newsletter the Woman Rebel in 1914, with considerable backing from unions and feminists. As Sanger and her friends sat around her dining room table addressing newsletters, they brain- stormed what to call their emerging movement for reproductive freedom. From that conversation, the term “birth control” was born. Encouraging working-class women to “think for themselves and build up a fighting character,” Sanger wrote that “women cannot be on an equal footing with men until they have full and complete control over their reproductive function.”

Sanger also began writing on women’s issues for the Call, a socialist news- paper. She developed two columns that later became popular books, What Every Mother Should Know (1914) and What Every Girl Should Know (1916). When she covered the topic of venereal disease, she went up against the US postal inspector Anthony Comstock, a one-man army against all things sexual. In 1873 Congress had passed the Comstock Law, which made illegal the delivery or transportation of “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” material and banned contraceptives and infor- mation about contraception from the mails.

Comstock censored her column, the first of many run-ins. He then seized the first few issues of the Woman Rebel from Sanger’s local post office. She got around him by mailing future issues from different post offices. Thousands of women responded to the newsletter, anxious for information on contraception.

Sanger’s next project was an educational pamphlet, Family Limitation, which described clearly and simply what she had learned in France about birth control methods such as the condom, suppositories, and douches. She planned to print

10,000 copies, but there was great demand from labor unions, representing members from Montana copper mines to New England cotton mills. She scraped up enough money to print 100,000. Over the years, 10 million copies would be printed, and the pamphlet was translated into thirteen languages. In the 1920s in Yucatán, Mexico, feminists distributed the pamphlet to every couple requesting a marriage license.

102 MARG ARET SANGER

But before she could distribute Family Limitation in the United States, Sanger had to go to court for the Woman Rebel, whose distribution was the “crime” for which she had received the arrest warrant. With very little time to prepare her de- fense and faced with a judge who seemed hostile to her cause, she made the snap decision to jump bail and flee, alone, to England. While in Europe, she visited a birth control clinic in Holland run by midwives, where she learned about a more effective method of contraception, the diaphragm, or “pessary.”

By the time Sanger returned to the United States, Comstock had died. Her hopes were raised that the laws might not be so vigorously enforced and that she might not have to stand trial. A well-publicized open letter to President Woodrow Wilson, signed by nine prominent British writers, including H. G. Wells, sup- ported Sanger and her work. Newspapers wrote about Sanger’s notoriety, and she gained sympathy when they reported that her five-year-old daughter, Peggy, had died suddenly of pneumonia. In the face of public pressure, the government dropped the case, but the laws remained on the books.

Sanger opened the nation’s first birth control clinic in October 1916 in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, primarily serving immigrant Jewish and Italian women. She, her sister Ethel Byrne (a registered nurse), and Fania Mindell (who helped translate for the immigrant patients) rented a small storefront space and distributed flyers written in English, Yiddish, and Italian advertising the clinic’s services. Sanger smuggled in diaphragms from the Netherlands and tried to re- cruit a physician to properly fit them in her patients, but no doctors were willing to face possible imprisonment. Although doctors were allowed to provide men with condoms as protection against venereal disease, they were not allowed to provide women with contraception.

Instead, Sanger and Byrne provided the services. The first day the clinic opened, they saw 140 women. Women—some from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts— stood in long lines to avail themselves of the clinic’s services. After nine days, the vice squad raided the clinic, and Sanger spent the night in jail. As soon as she was released, she returned to work. Again, the police came, and this time they forced her landlord, a Sanger sympathizer, to evict them.

Following the eviction, Sanger, her sister, and two others were arrested for “cre- ating a public nuisance.” Ethel was the first to be convicted, and she responded to her sentence of thirty days of hard labor by going on a hunger strike. After four days, the judge ordered her to be force-fed; it was the first time this punishment had been used in the American penal system. Headlines around the nation publi- cized her plight. “The whole country seemed to stand still and anxiously watch this lone woman’s fight against an iniquitous law,” wrote a reporter for the Birth Control Review in 1917. Ethel almost died before Sanger was able to secure a par- don from the governor and rescue her.