Once we brush past shallow rhetoric about “negotiations,” the Republican line on the debt ceiling boils down to this: other presidents have paid a ransom to avoid catastrophic economic consequences, so President Obama should, too.

The talking point — which GOP pollsters hadn’t formulated during the Republicans’ first debt-ceiling crisis in 2011 — may even sound fairly reasonable, at least at first blush, for those who don’t know better. It also makes it seem as if GOP lawmakers are doing something routine when they threaten to hurt Americans on purpose. If it’s happened before, the argument goes, then folks like me are wrong to use words like “unprecedented.”

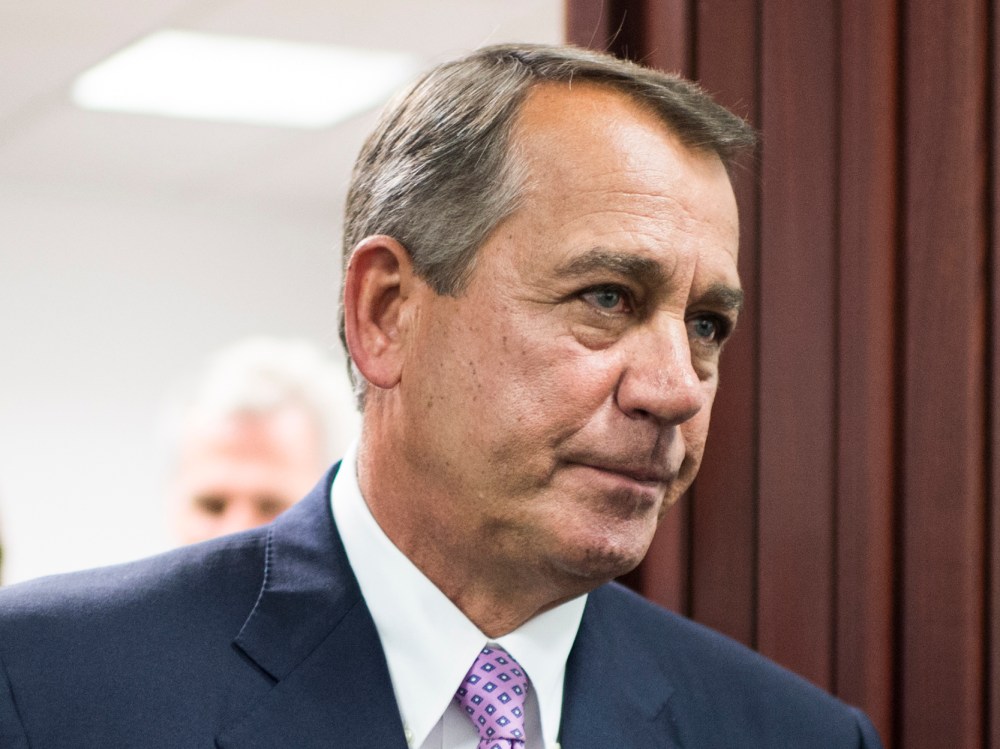

Here was House Speaker John Boehner’s (R-Ohio) pitch yesterday:

“Listen, the debt limit is right around the corner. The president is saying, ‘I won’t negotiate. I won’t have a conversation.’ Even though, President Reagan negotiated with Democrats who controlled the Congress back then. Even though President George Herbert Walker Bush had a conversation about raising the debt limit. During the Clinton administration, there were three fights over the debt limit. You and I participated in several of those. And even President Obama himself in 2011, went through a negotiation.

“Now, he’s saying., ‘No. I’m not going to do this.’ I’m going to tell you what, George. The nation’s credit is at risk because of the administration’s refusal to sit down and have a conversation.”

This has quickly become the key arrow in the GOP’s quiver, serving as the basis for weekly addresses, op-eds, and countless media interviews. The ubiquitous argument has two main prongs: (1) other presidents have negotiated over the debt ceiling; and (2) debt-ceiling negotiations routinely lead to debt-reduction agreements.

Not surprisingly, the argument is wildly misleading, but given the severity of the crisis and the talking point’s importance to Republicans, it’s probably worth considering in detail.

First, a little common sense is in order. The right would have us believe that debt-ceiling increases and debt-reduction agreements simply go together — they’re the chocolate and peanut butter of U.S. fiscal policy. But even casual observers might notice an obvious flaw: the debt ceiling has been raised about 90 times over eight decades, and there haven’t been 90 debt-reduction agreements over that period. So just on a surface level, we know there’s a serious flaw in the argument.

Second, and more important, are the details Republicans choose to overlook. For example, since President Reagan, Congress has approved 45 debt-ceiling increases. How many of them were tied to budget deals? Seven. In other words, over the last several decades, 38 out of 45 debt-ceiling increases were not part of debt-reduction agreements (or any other policymaking measures).

Indeed, we should highlight an inconvenient detail: many leading Republican members of Congress, including a cast of characters that includes John Boehner, Eric Cantor, and Mitch McConnell, have each voted for clean debt-ceiling increases unrelated to budget deals.