Kevin Williamson covers some well-traveled ground this week, making the case that, despite popular political “myth,” it’s the Republican Party that’s the “party of civil rights.

That Republicans have let Democrats get away with this mountebankery is a symptom of their political fecklessness, and in letting them get away with it the GOP has allowed itself to be cut off rhetorically from a pantheon of Republican political heroes, from Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to Susan B. Anthony, who represent an expression of conservative ideals as true and relevant today as it was in the 19th century.

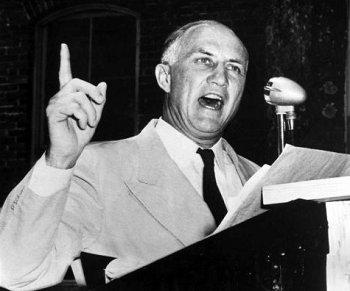

Perhaps even worse, the Democrats have been allowed to rhetorically bury their Bull Connors, their longstanding affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan, and their pitiless opposition to practically every major piece of civil-rights legislation for a century.

The right brings this up from time to time, sometimes as a defensive reaction when Republicans are feeling vulnerable on civil rights, but usually as a way of trying to convince African-American voters to ignore the last several decades and break from the Democratic coalition.

But the historical record doesn’t do the GOP any favors.

The Democratic Party, in the first half of the 20th century, was home to two broad, competing constituencies — southern whites with abhorrent views on race, and white progressives and African Americans in the north, who sought to advance the cause of civil rights. The party struggled with this conflict for years, before ultimately siding with an inclusive, liberal agenda.

As the party shifted, the Democratic mainstream embraced its new role. Republicans, meanwhile, also changed. In the wake of Democratic President Lyndon Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act, the Republican Party welcomed the white supremacists who no longer felt comfortable in the Democratic Party. Indeed, in 1964, Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater boasted of his opposition to the Civil Rights Act, and made it part of his platform. It was right around this time when figures like Jesse Helms and Strom Thurmond made the transition — leaving the progressive, diverse, tolerant Democratic Party for the GOP.

In the years that followed, Democrats embraced their role as the party of inclusion and civil rights. Republicans, meanwhile, became the party of the “Southern Strategy,” opposition to affirmative action, campaigns based on race-baiting, vote-caging, discriminatory voter-ID laws, and politicians like Helms and Thurmond.

Williamson’s piece emphasizes Democratic votes from mid-19th century. His observations aren’t wrong — Democrats were, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War — on the wrong side.