With fundraising totals reaching extraordinary heights, there’s no doubt that both President Obama, Mitt Romney, and their assorted allies will have plenty of resources between now and Election Day.

But it’s worth noting that while neither side will suffer from empty coffers, there’s a clear qualitative difference in the kind of donors that separate one campaign from the other. The Boston Globe had an interesting report on this the other day.

When the head of JPMorgan Chase met with shareholders to answer for a trading loss of more than $2 billion Tuesday, it was against an evolving political backdrop: Donors from big banks are betting on Mitt Romney to defeat President Obama and repeal new restraints on risky, large-scale investments.

“There’s no doubt that there’s been a big diminution of support for the president,” said William M. Daley, Obama’s former chief of staff and a former top JPMorgan Chase executive. “People in the financial services sector are saying, ‘The president has been too tough on us, both in policy and on rhetoric.’ ”

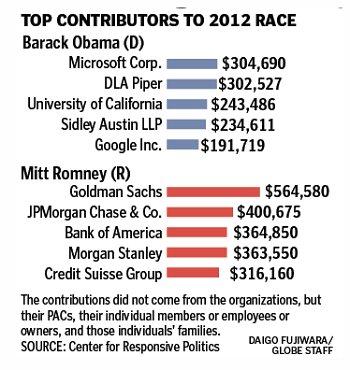

The top five donor groups in Romney’s campaign are individuals and political action committees associated with large financial institutions, led by Wall Street giants Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase, according to information compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan research group that tracks campaign donations.

While in 2008, financial institutions were far more inclined to back the Democrat, those contributions have seen a sharp decline. The most generous contributors to Obama’s re-election campaign include exactly zero Wall Street backers: the top donor groups include individuals and PACs affiliated tech giants (Google and Microsoft), law firms, and academia.

Why does this matter? For one thing, for voters who care about such things, Romney’s overwhelming support from Wall Street could prove to be politically problematic — just four years ago, these financial institutions’ recklessness and mismanagement nearly destroyed the global economy. Wall Street is not at all popular with the American mainstream, so being known as Wall Street’s candidate isn’t exactly a selling point.

For another, these generous contributions do not occur in a vacuum — if Romney’s elected, he’ll pursue a policy agenda intended to make these Wall Street donors very happy.

Indeed, consider what the presumptive Republican nominee said just last week about JPMorgan’s latest bad bets, which cost at least $2 billion: “This was a loss to shareholders and owners of JPMorgan and that’s the way America works. Some people experienced a loss in this case because of a bad decision. By the way, there was someone who made a gain.”

The point of the argument was simple: there’s no need for safeguards or layers of accountability to protect the integrity of the system; it’s better for government to just get out of the way and let his Wall Street supporters do as they please. The market, the argument goes, will work itself out.