As California continues burning through another historic period of wildfires the news cycle can become jammed with evacuations, environmental fears and involuntary power shutoffs. All this because intense Santa Ana Winds have collided with extremely dry land and power lines which have set many of the fires.

As part of the state’s ongoing effort to combat fires, it’s no secret that prisoners have been working on the front lines of the fight, often as hand units, doing similar work to California’s seasonal wildland firefighters.

California’s Conservation Camp is a rehabilitation and re-entry program in California under the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation where inmates do this kind of firefighting work. It began in 1946 and operates currently in 27 counties in California. It’s billed as a career pipeline that gets prisoners ready for jobs.

“An inmate must volunteer for the fire camp program; no one is involuntarily assigned to work in a fire camp,” Alexandra Powell the Public Information Officer for CA Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said. Participants are required to have “minimum custody” status, the lowest classification of crimes.

CAL FIRE is the organization that trains and deploys the prisoners. Powell says prisoner firefighters receive the same training, education and equipment as California’s seasonal wildland firefighters.

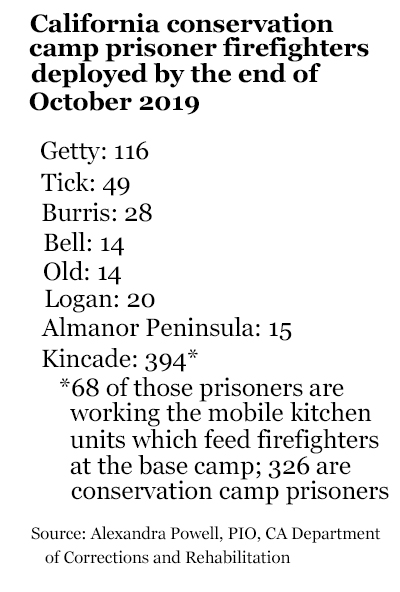

Approximately 2,150 of 3,100 prisoners are currently qualified to be on the front lines of fighting these fires, according to Powell. The CDCR has previously stated that the program saves the state between $90 and $100 million a year in firefighting costs, but currently has no confirmed dollar figure.

Deputy Chief Scott McLean with CAL FIRE communications said the prisoner populations are essential.

“Being able to deal with the prevention side which is extremely important, where the inmates come into play as well. They just don’t fight fire. We have project work that we’re all involved in as far as prevention out there in the wild land area,” McLean said.

While the camps provide training and education for prisoners, there are concerns about whether the opportunity for employment after leaving the program are realistic. Neither CAL FIRE nor the Conservation Camp had complete records of post-program job placement.

Last year, CAL FIRE and CDCR started a post-release training center in Ventura, California that offers more advanced training to help place more prisoners in entry-level firefighter positions, including with CAL FIRE itself. But although CAL FIRE and private municipal firefighting crews do not require EMT licenses, most California firefighting positions are union jobs under California’s Professional Firefighters Union, all of which require an EMT license. As state regulations stand today, inmates have to wait 10 years after their release before being eligible to receive their EMT license and therefore do not qualify for the majority of full time firefighting positions in the state.

“It may sound like that’s exactly what we would want, a pipeline for these former inmates to know that there is a future for them as a firefighter, but the pipeline, there is nothing in the end,” laments California Assemblymember Eloise Reyes.

Reyes has been an advocate for changing the California code restricting inmates from receiving an EMT license. She’s tried, and failed, to pass legislation to amend the rules for multiple years in a row.

“We still have firefighters who fought in the conservation camp and still were not able to get a job as a firefighter,” Reyes said, “They’re all felons, they’ve all been convicted of felonies and [with] that alone, you cannot get an EMT license with a felony conviction.”

The California Professional Firefighters Union is Reye’s biggest opposition in changing the law.

“There may be an issue about trust,” Reyes says. “I think that when we recognize that nearly 8 million Californians have a criminal conviction. When we look at the fact that if 80% of jobs in California require some sort of a license or certificate for clearance and we’re shutting out an entire group of potential workers.”

Carroll Wills, Communications Director for California Professional Firefighters (CPF), says previous attempts at legislation have been unrealistic.