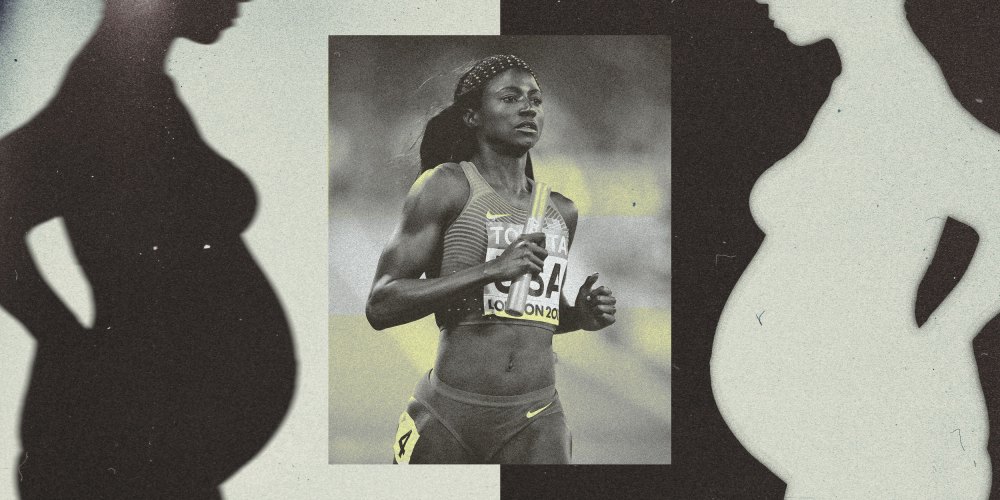

The news last month that 32-year-old sprinter and Olympic medalist Tori Bowie had died was sad enough. This week’s news that Bowie died of complications related to pregnancy adds to the sorrow and brings fresh attention to one of our country’s most awful statistics: The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate of any high-income country, and the problem is only getting worse. The rate of maternal mortality rose from 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2018 to 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2021. Black women like Bowie are disproportionately affected.

The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate of any high-income country, and the problem is only getting worse.

How bad is it? In 2021, Black women died in childbirth 2.6 times more often than white women did. Even when adjusted for social and economic factors, Black women have worse outcomes. The pregnancy-related mortality ratio for a Black woman who’s earned a college degree is nearly twice that of a white woman with less than a high school diploma. It doesn’t matter whether you are rich or poor, educated or not, an OB/GYN like I am or even a world-class athlete. For Black women, the color of your skin can determine whether you and your baby survive pregnancy and childbirth.

Bowie made her mark as a star Olympic sprinter, winning silver in the 100 meters and bronze in the 200 meters at the 2016 Summer Games in Brazil. She was the anchor on the 4×100 team that won gold. She had access to care. Why did she experience the same tragic outcome as so many other Black women? And why have two other women she won gold with had bad childbirth experiences?

Allyson Felix, who posted a picture of the gold medal-winning relay team that Bowie anchored in Rio de Janeiro on Twitter, wrote: “Three of us tried to give birth. Two of us experienced near-death complications. One of us died.” In 2018, Felix delivered her daughter via an emergency C-section because of severe preeclampsia. Tianna Madison has written that she “went into labor at 26 weeks,” went to the hospital with “my medical advance directive AND my will” and was “NOT AT ALL confident that I’d be coming home.”

Why is it that so many Black women have such stories? As an obstetrician and gynecologist and the medical director of my state’s maternal mortality review committee — and also as a Black woman who didn’t always get the best care when I was pregnant — I think the reasons include:

Fear of the health care system. For far too long, the health care system has devalued the voices of Black women. Tennis superstar Serena Williams, who’d had a history of dangerous blood clots in her lungs before she was pregnant, said that she sensed something bad was happening after she had her daughter, Olympia, via an emergency C-section in 2017 but that she had to demand a CAT scan over the objections of the medical staff. That scan found blood clots in her lungs that could have killed her.

When I began feeling abdominal pains at 25 weeks of pregnancy, the doctors didn’t run on me the tests that I would have run on a patient in my office with those symptoms.

When I was away at a medical conference and began feeling abdominal pains at 25 weeks of pregnancy, the doctors didn’t run on me the tests that I would have reflexively run on a patient who appeared in my office with those symptoms. When I returned home, my doctor told me I was in danger of spontaneous preterm birth and immediately put me on medication and bed rest. As I’ve written previously, though I’m an expert in treating pregnant women, when I was before an unfamiliar medical team, I didn’t want to come across as “the angry Black woman,” which meant “I put my son’s life and my own life in danger because of politeness.”

There are numerous examples of Black women’s having their pain and distress ignored. Stories about the indifference from doctors and nurses have left many Black women afraid to interact with the health care system and seek alternative methods for care during pregnancy and birth.

According to a November report from the National Vital Statistics System, there was a 19% increase in the number of home births from 2019 to 2020 and a 13% increase from 2020 to 2021. While the start of the Covid pandemic most likely explains some of that increase, the aversion to giving birth in a hospital wasn’t evenly spread. From 2019 to 2020, the number of home births increased by 21% for white women and by 36% for Black women. From 2020 to 2021, the rate increased by 10% for white women and by 21% for Black women.

These are my teammates. We are Olympic champions. Three of us tried to give birth. Two of us experienced near-death complications. One of us died. We have to, and we will do more. Tori’s death cannot and will not be in vain.https://t.co/cE4o00nP9c

— Allyson Felix (@allysonfelix) June 15, 2023

While the desire for home births is understandable, giving birth at home isn’t always associated with better outcomes. The risk of the baby’s dying is increased twofold, and the risk of neonatal seizures or neurologic dysfunction is threefold. Of course, fear of being disrespected or disregarded by doctors isn’t the only thing that might factor into a woman’s decision to deliver outside the health care system, but after the countless examples of the implicit bias Black women are subjected to in the health care system, it can’t be discounted. According to reports, Bowie, as many of my patients have, had expressed concern about delivering in a hospital.

Authorities who had been asked to conduct a welfare check at Bowie’s Florida home discovered her body May 2. An autopsy from the Orange County Medical Examiner’s Office said she was in active labor when she died of complications that included respiratory distress and eclampsia.