Thursday, 5:30 p.m.

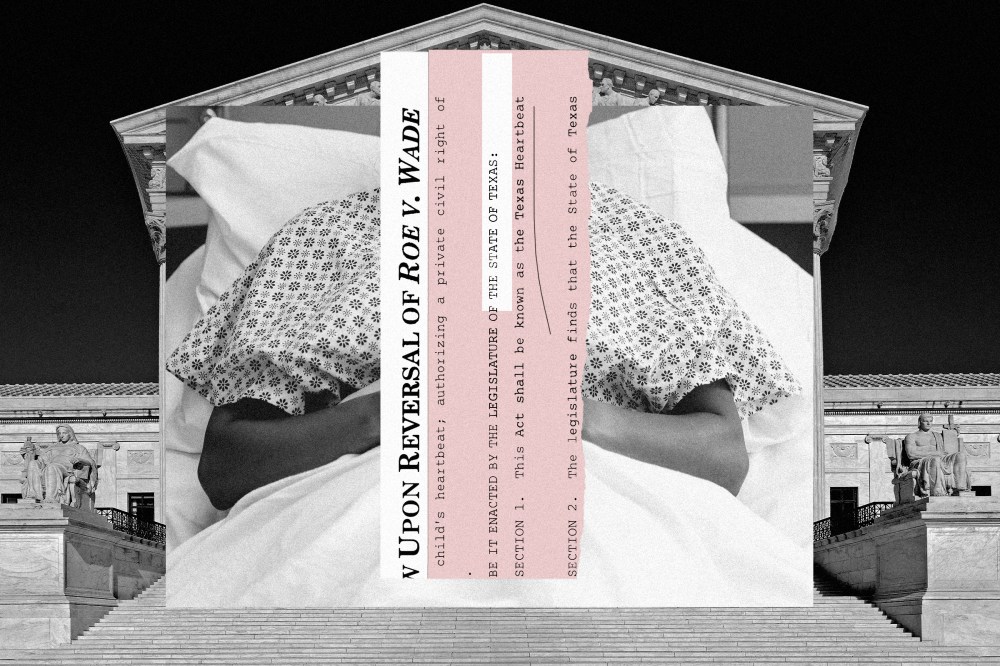

My wife says she doesn’t feel right. She’s almost 13 weeks pregnant with our second child. She is bleeding and has severe abdominal pain. We live in rural Texas, where options are limited.

At the nearest emergency clinic, my wife goes inside alone, while I wait in the truck with our 9-month-old daughter. We learn the fetal heartbeat stopped about a week ago. Unless you’ve been there yourself, it’s impossible to fathom the devastation we feel.

We’re told there’s a high risk of infection if we don’t act fast. We have two options. One is a procedure called “dilation and curettage,” which removes the contents of the uterus. The other is a take-home pill called misoprostol, which causes the pregnancy to be expressed. Both options are the standard of care for people with incomplete miscarriages like my wife’s, and though a D&C is used in some abortions, the procedure is legal in Texas if there’s no fetal cardiac activity detected. Yet the practitioners at the clinic refuse to perform it. Instead, they write her a prescription for misoprostol.

It’s too late for me to go to the pharmacy tonight. At home, my wife tries to sleep, but I’ve never heard her cry like this. She cries all night.

Friday, 7:00 a.m.

I’m first in line when the pharmacy opens, and I grab the small paper bag of misoprostol. It can cause bleeding and cramping while it helps flush the uterus. My wife is a strong Texan woman, but the pain proves almost unbearable.

We call the emergency clinic for guidance. Because my wife is expelling bright-red blood, not brown, the medical staff explains the pill isn’t working.

Though proven effective, misoprostol — like any medication — doesn’t work for everyone. We need another option.

Saturday, 6:00 a.m.

My wife hasn’t slept. She’s still bleeding.

We call the emergency clinic as soon as they open. We learn misoprostol can sometimes take two or three attempts to fully work. They ask us to come back in.

There’s a new doctor this time, an older man. He’s aware of my wife’s incomplete miscarriage and history of care. My wife hears him huffing outside the exam room: “I’m not giving her some pill so she can go home and have an abortion.”

Then he comes in and says he won’t prescribe her the pill “considering the current stance.” He doesn’t mention a D&C. Even the nurse is visibly shocked.

When the doctor finally returns, she deems my wife’s condition ‘not enough of an emergency.’

We call another hospital — farther away, but one we trust. For the third time this weekend, my daughter and I sit in the truck outside a hospital while I clutch my phone, waiting for updates. Inside, my wife has to start the process all over again — new scan, new questions, more poking and prodding — only to reconfirm what we already know.

Then, the strangest thing happens. The medical staff disappears. For hours. When the doctor finally returns, she deems my wife’s condition “not enough of an emergency” to perform a D&C. If we want the procedure, the soonest we can get it is at least a week away.

The staffers know my wife is still bleeding. They know there’s been no fetal heartbeat for over a week. They know the risks of infection and sepsis. But they don’t want to risk criminal prosecution. Because in Texas, they can now face a $100,000 fine or life in prison for inducing anything that could be interpreted as an abortion after six weeks of pregnancy.