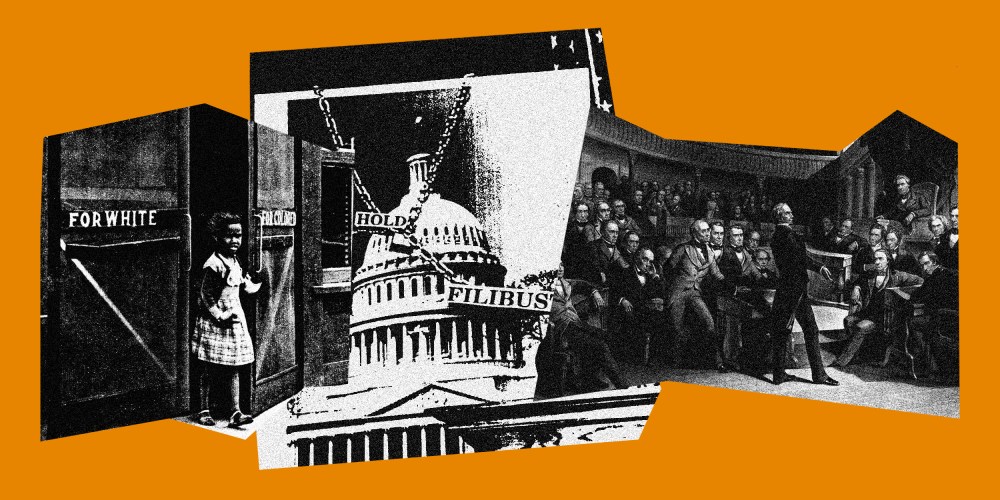

In a recent news conference, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., made a startling observation that quickly went viral. The Senate filibuster, he remarked, “has no racial history at all. None. There’s no dispute among historians about that.”

Then, as now, filibusters were often used to block measures to expand Black rights and political participation.

As a historian, I can tell you that this could not be further from the truth. Even a brief examination of U.S. history reveals that it is impossible to separate the filibuster from the history of racism and white supremacy. Then, as now, filibusters were often used to block measures to expand Black rights and political participation.

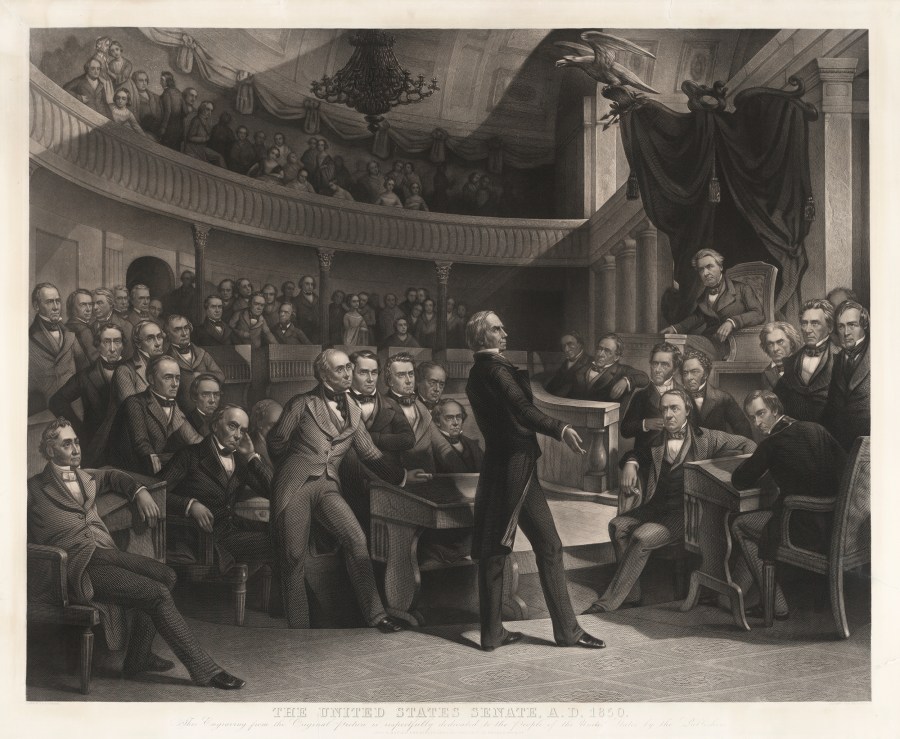

In 1841, during a debate over the formation of a national bank, Sen. Henry Clay proposed a rule to “limit debate.” The idea immediately sparked resistance, some of it from John C. Calhoun, a senator from South Carolina and renowned supporter of slavery.

On the surface, the resistance stemmed from the belief that debates on the Senate floor should never be limited. It was framed as a matter of principle — the right to express oneself for as long as one desired to attempt to delay proceedings and even prevent the passage of legislation. A closer examination, however, reveals that Calhoun and others orchestrated the 1841 filibuster to protect the interests of Southern planters and, by extension, the institution of slavery.

Calhoun, recognized as one of the architects of the modern filibuster, was deeply invested in upholding slavery and protecting the interests of slaveholders. And what he recognized during the 1840s was that he could effectively use the filibuster to obstruct efforts in the Senate that might undermine the South’s vested interest in slavery.

Other senators quickly followed suit. Of the 40 filibusters that took place in the Senate from 1837 to 1917 (when the cloture rule was established), at least 10 directly addressed racial issues. The use of filibusters to block Black political rights significantly expanded during the 20th century, as civil rights activists across the country fought to introduce legislation to empower Black Americans and white senators turned to the filibuster as one method to block their efforts. This continued through a series of coordinated filibusters from the post-World War I era to the advent of the modern civil rights movement.

Frequently, the filibuster was used to block anti-lynching legislation.

And it’s no coincidence that the vast majority of measures blocked in the Senate during that time addressed matters of civil rights. Frequently, the filibuster was used to block anti-lynching legislation, as was done by Sen. Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi, who used it often to strategically prevent any measure meant to end the violent practice. His common use of the filibuster to maintain white supremacy garnered him the title “filibuster king” from The Chicago Defender, a Black-owned newspaper.

Bilbo was known to speak for hours to obstruct any measure that would have granted rights and protections to African Americans. In 1938, for example, he launched a filibuster against a proposed federal anti-lynching bill set forth by the NAACP.

There’s a reason the NAACP repeatedly made ending the filibuster one of its top priorities in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s.

— Kevin M. Kruse (@KevinMKruse) March 25, 2021

They understood how significant a tool it was for white supremacists. pic.twitter.com/1SWRP1tsH4

Bilbo’s use of the filibuster to block federal anti-lynching legislation in 1938 was only one of many during that period; at one point he used the opportunity to argue that African Americans needed to leave the U.S., going so far as to recommend that they relocate to Liberia. Southern senators would go on to use filibusters to defeat anti-lynching bills well into the 1940s.

While the filibuster was widely used for such purposes, Bilbo made a name for himself not only because of his reliance on the practice, but also because of his blatant admission of his motives. He could hardly conceal his disdain for Black people, and his racist ideas were no secret. The filibuster allowed Bilbo to move from words to actions — he could stand in the way of Black progress, and he could do so with the support of like-minded colleagues in the Senate.

In 1943, when activists tried to repeal the use of poll taxes — a well-worn voter suppression tactic that disenfranchised African Americans in his home state of Mississippi — Bilbo pledged to “filibuster this damnable bill for 18 months to kill it.”

Determined to keep poll taxes firmly in place, Bilbo prepared a speech that he was ready to deliver for 18 months — until the end of the Senate session in 1945 — if needed. In the end, the filibuster brought an end to the 1943 anti-poll tax legislation, though it failed before Bilbo could embark on his planned 18-month rant.