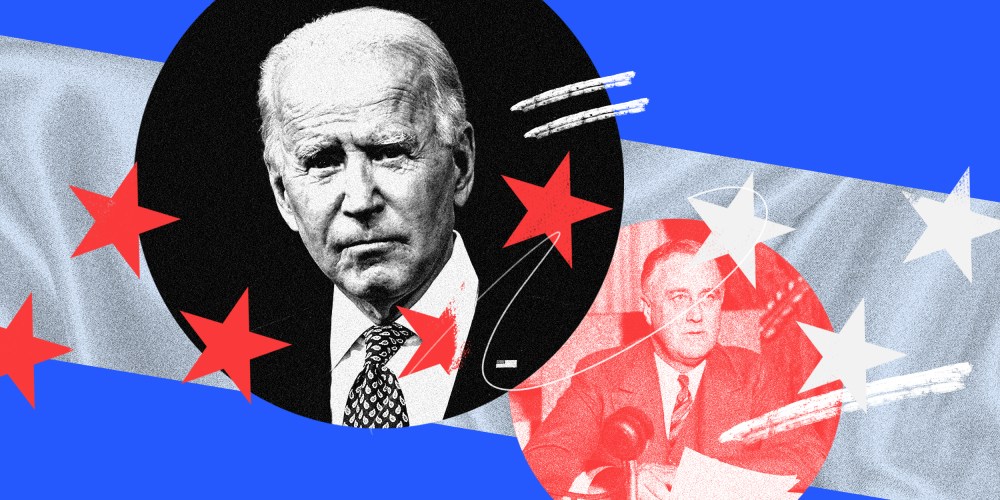

Ahead of President Joe Biden’s 100-day mark, the FDR comparisons abound. Jonathan Alter, author of a book on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s own first hundred days, called Biden “FDR’s heir” in a New York Times op-ed. David Gergen, former adviser to Republican and Democratic presidents alike, said the 46th president “bears some important similarities” to the 32nd. During the election campaign, Biden’s aides even told New York magazine their candidate was planning an “FDR-size presidency.”

But that’s not the whole picture. Even Gergen conceded that “Biden is no Roosevelt” — not yet, at least. Whether he actually lives up to that mantle will depend not just on how well Biden leads but on how well he listens to the voices urging him toward a more progressive future.

Just by the numbers, Biden hasn’t matched FDR’s opening intensity. Roosevelt pushed 15 major bills through Congress in a frenzy of activity between March and June 1933. Since January, Biden has passed, well, one. Don’t get me wrong: The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan is the most ambitious and progressive legislation of my lifetime. Who would have imagined Biden would try to emulate Roosevelt or Lyndon B. Johnson in his first three months?

More important than the quantity of bills passed, though, is the quality. Both of those Democratic presidents delivered lasting institutional change — think Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid. Biden has yet to be able to say the same.

So let’s look beyond the first 100 days. Biden could still emulate FDR in another crucial way. It is said that a group of civil rights activists and labor leaders, including A. Philip Randolph, once met with Roosevelt prior to the start of World War II to insist he use the power of the presidency to take action against discrimination in the workplace. “You’ve convinced me,” FDR responded, having listened to them lay out their demands. “Now go out and make me do it.”

The story is almost certainly apocryphal (though, to be fair, singer Harry Belafonte claimed to have heard a version of it from Eleanor Roosevelt herself.) True or not, the point of the story is clear: Politicians inside the system need allies outside of it; outsiders willing to publicly pressure them and, on occasion, provide cover for bold, outside-the-box moves. To quote essayist Ta-Nehisi Coates: “Politicians respond to only one thing — power. This is not the flaw of democracy, it’s the entire point. It’s the job of activists to generate, and apply, enough pressure on the system to affect change.”

Some on the left have argued the story of FDR’s response to Randolph has been misinterpreted because “politicians, as a rule, do not like being pressured by movements they cannot control and often lash out at those who demand that they take more principled or politically risky stands,” as Dissent put it.

This was definitely how Biden behaved, at times, during the Democratic primaries. He never pretended to be at the head of a transformational movement, a la his former boss, Barack Obama. He didn’t enter office backed by a loyal cult, as his predecessor, Donald Trump, did.

Yet he and his administration have spent these first 100 days embracing the progressive wing of his party, along with labor unions, youth groups, climate campaigners and sundry activists. “Progressives say they’re being included, heard and respected by the Biden White House,” Politico reported in February.

Compare and contrast this outreach with the Obama era, in which White House press secretary Robert Gibbs dismissed people on the “professional left” who “ought to be drug-tested,” and White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel denounced liberal activists as “f—ing retarded.”

Biden, on the other hand, proudly invoked Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ support for the American Rescue Plan in the immediate aftermath of its passage through the Senate. His chief of staff, Ronald Klain, has been dubbed the “left whisperer,” having become “a point of rapid response for many on the left who are angling to get within earshot of the president,” The Daily Beast wrote.

Real access has been matched by real impact. Does anyone really believe the Biden who launched his presidential campaign in 2019 looking for a “middle ground” on climate issues would have committed to cutting U.S. carbon emissions in half by 2030 without pressure from groups like the Sunrise Movement?

During the Democratic primaries, the youth-led environmental group gave Biden’s climate plan an “F.” Since Biden’s inauguration, however, the group has been pushing at an open door in the White House. “I feel like we’re getting a little bit spoiled for future presidents,” Varshini Prakash, the movement’s co-founder, told the Washington Post in April. “I think it’s pretty wild that there’s a [White House] chief of staff who you can email who actually gets back to you.”

Outside pressure works in myriad ways. Not only have activists pushed the centrist Biden toward more progressive goals on everything from the climate to infrastructure, they have also forced the administration to change course on certain issues, often reversing bad decisions or policies in the process.

On March 7, White House communications director Kate Bedingfield told CNN the president’s “preference is not to end the filibuster. He wants to work with Republicans, to work with independents.” One week later, Klain told me Biden “believes if we could leave the filibuster in place, that’s what he prefers.”

The Biden administration has proved itself to be open to outside pressure and willing to do, or at least seem to be doing, the right thing.

Yet just two days after that, with a growing chorus of voices in Congress as well as progressive activists in groups like Indivisible demanding action on the filibuster, Biden himself was telling ABC News he was actually in favor of reform and suggesting the re-introduction of the so-called talking filibuster: “That’s what it was supposed to be.”