Andrew Brannan danced a jig in the middle of the road and dared the sheriff’s deputy to open fire.

“Here I am!” he sang out. “Shoot my f– a–!”

Brannan’s arms waved wildly in the air as he jumped from one foot to the other. He had been pulled over along the tree-lined road in a rural Georgia area for speeding at 98 mph. But within minutes, the camera mounted on the deputy’s dashboard showed a routine traffic stop unraveling into a deadly scene.

Laurens County Deputy Sheriff Kyle Dinkheller radioed for backup as Brannan continued with his taunts. The 22-year-old had been nearing the end of his shift when Brennan’s white pickup truck sped by that early evening in January. “Sir, get back now,” the deputy sheriff yelled repeatedly in a near shriek. The fear and desperation in his voice escalated with each new demand. “Get back!” Seconds later, Brannan barreled toward Dinkheller, and then backed away while screaming obscenities.

“I am a god— Vietnam combat veteran,” Brannan shouted as he retreated to his car. He returned with an assault rifle in hand. A gun fight ensued between the two men, killing Dinkheller.

That was 1998, before much was known about symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Before young soldiers served two, three or even four tours in Iraq or Afghanistan. And before the American public came to terms with the brutal impact war can have on a soldier’s mind.

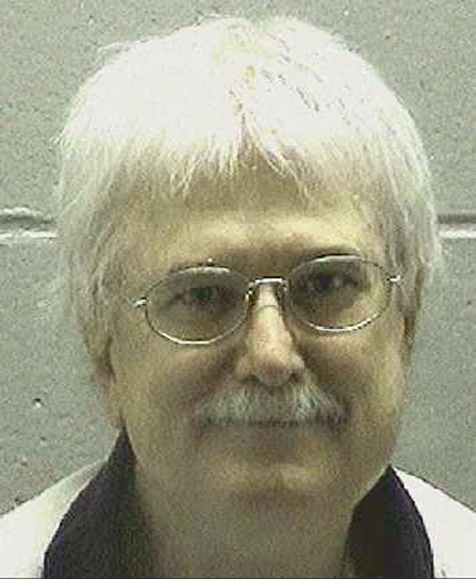

And Tuesday, after spending 14 years on death row, Brannan became the first condemned man to be executed in 2015.

RELATED: Executions in US at 20-year low

In his 2000 trial, Brannan pleaded guilty to murder charges in Dinkheller’s death, for reasons of insanity. A psychologist brought by the defense testified that the episode was likely the result of a flashback to Brannan’s time in combat. But a jury ultimately rejected Brannan’s insanity plea, convicted him and a death sentence was handed down.

Brannan had no criminal history when he opened fire on the side of that Georgia road. The Department of Veterans Affairs had previously declared Brannan as “100% disabled” with PTSD. He suffered from depression and battled with suicidal thoughts. In 1994, a VA psychiatrist diagnosed Brannan with bipolar disorder. According to his attorneys, Brannan had stopped taking his meds five days before the murder.

The U.S. Supreme Court declined without comment to step in the eleventh hour to stay the execution. With his legal efforts to appeal the death sentence almost exhausted, Brannan was executed by lethal injection Tuesday night in Jackson, Georgia. Just a day earlier, Brannan’s legal team tried a last-ditch effort to seek clemency, arguing that the jury back in 2000 was offered an incomplete picture of Brannan’s military service and history of mental illness.