Hungry students don’t enter the on-campus food pantry at New York’s LaGuardia Community College; instead they sit in an office in the college’s financial services center while a staff member or volunteer runs upstairs to get their food, bringing them unmarked grocery bags to take home.

Little more than an unlabeled office, containing a series of unmarked file cabinets, the pantry goes undetected to most — and that’s the point.

Dr. Michael Baston, the college’s vice president of Student Affairs, says the whole process is designed to be invisible.

“We did this because we feel like it is a stigma reducing strategy,” he said. “Because we want students to feel like whatever the resource they need to sustain themselves, that would be available to them.”

Battling stigma is a challenge for food pantries of all stripes, but the struggle appears to be especially pronounced on college campuses. After all, universities are supposed to be islands of relative privilege. If you can afford to spend thousands of dollars a year on a college education, the thinking goes, you can’t possibly be hungry enough to require emergency food assistance.

Rhondalisa Roberts, a LaGuardia sophomore and food pantry client, has witnessed that stigma firsthand. She says that when she suggested that a hungry classmate of hers visit the pantry, the classmate told her, “Oh, I’m not going to go there. I’m not poor.”

“It’s very, very alarming,” Roberts told msnbc. “Most students have a negative stigma when it comes to receiving help for food. Everybody doesn’t want to receive food or seem needy, even when they are in dire need of resources.”

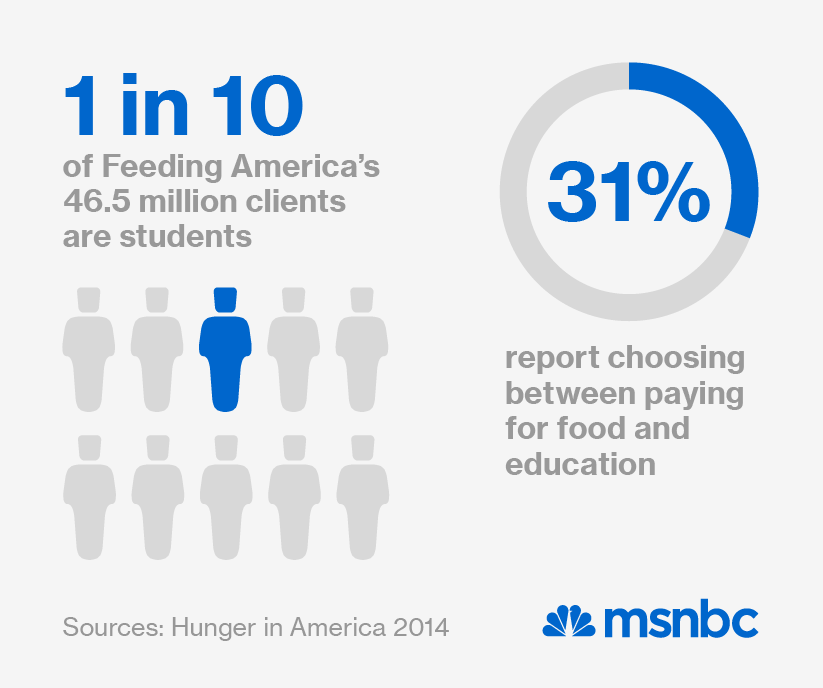

It’s difficult to track just how many college students are in dire need, but new data from the country’s largest emergency food service network suggests that the number is at least in the millions. Feeding America’s 2014 Hunger in America report estimates that roughly 10% of its 46.5 million adult clients are currently students, including about two million people who are attending school full-time. Nearly one-third of those surveyed—30.5%—report that they’ve had to choose between paying for food and covering educational expenses at some point in the last year.

Feeding America, a network of some 46,000 emergency food service agencies in the United States, releases its Hunger in America report once every four years. This latest iteration of the report, which is based on a survey of more than 60,000 Feeding America clients, is the first to include data about college students in need of emergency food services. The new research suggests that America’s chronic hunger emergency has not spared institutes of higher learning.

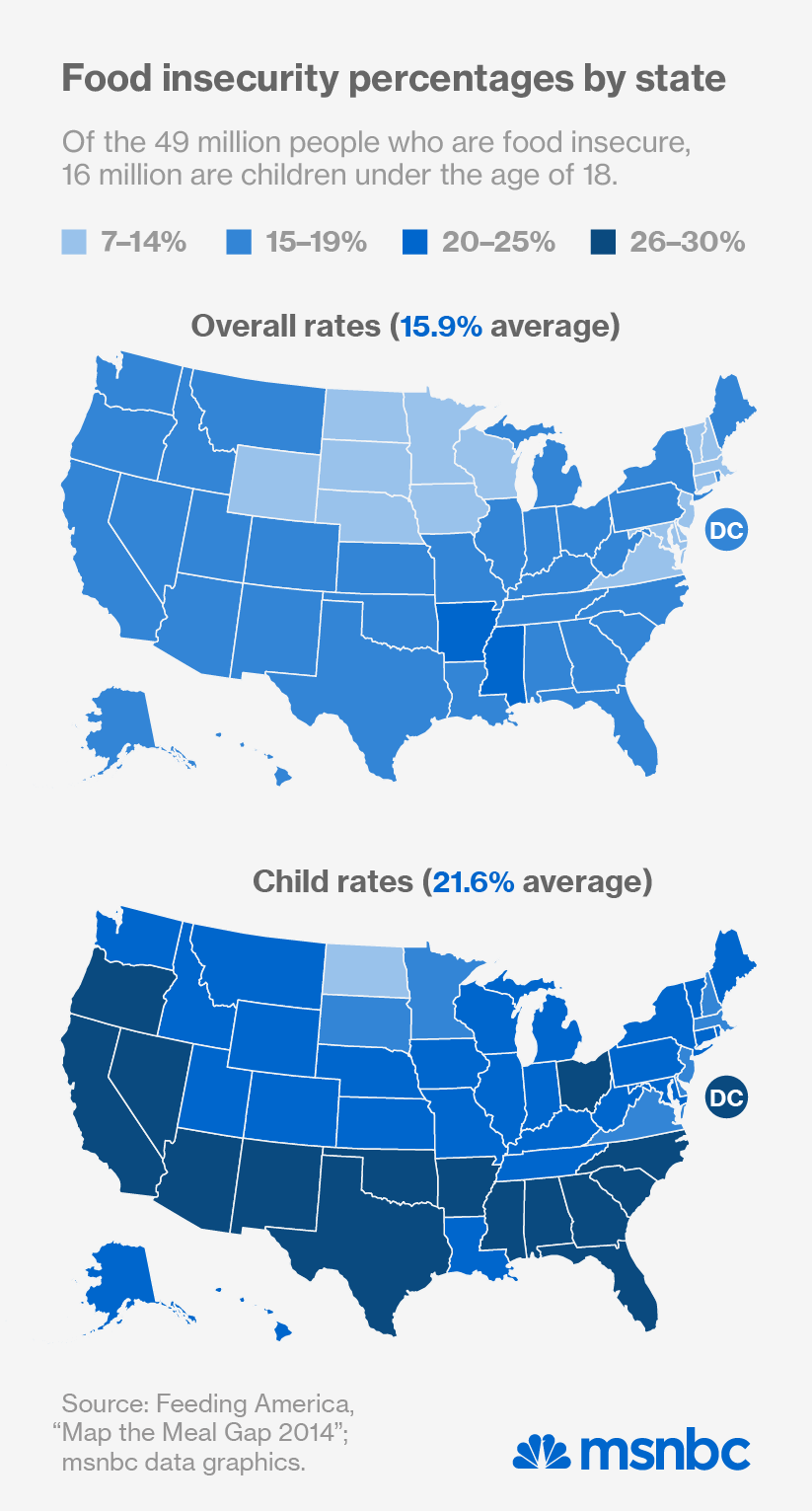

Maybe that should come as no surprise, given that food insecurity—defined by the Department of Agriculture as lack of “access … to enough food for an active, healthy life”—has been rising steadily for years. In part that’s due to the Clinton and Reagan administration’s significant revisions to the welfare state. Yet the situation didn’t become a true crisis until after the 2008 financial collapse, which caused food insecurity to rise by 24% in the space of a single year, according to USDA figures. In response, the federal government approved an emergency transfusion of funds into the food stamp program; but then it began to roll back those additional funds in November 2013, even though food insecurity had never returned to pre-2008 levels. The result was an unprecedented state of permanent emergency for emergency food assistance programs across the country.

As food insecurity rose, it also began to affect households that had never experienced it before. Data published by Feeding America in April suggests that 27% of food insecure people don’t qualify for food stamps because their incomes are too high. And even as food insecurity continued to climb, so did college enrollment rates, in part because college is seen as a stepping stone to economic security.

“Poor people and people who struggle with food insecurity didn’t used to go to college. … If they were going to get education, they were going to get the free part and that’s it,” said Sara Goldrick-Rab, professor of educational policy studies and sociology at the University of Madison-Wisconsin. “But there’s been such a strong cultural push and a strong economic push for college that people with no means are pursuing it.”

As low-income populations have gone to college and food insecurity has risen up to swallow the lower rungs of the middle class, hunger has spread across America’s university campuses like never before. In some places, it’s practically a pandemic: At Western Oregon University, 59% of the student body is food insecure, according to researchers from Oregon State University (OSU). A 2011 survey [PDF] of the City University of New York (CUNY) found that 39.2% of the university system’s quarter of a million undergraduates had experienced food insecurity at some time in the past year.

But it’s not just undergraduates: the number of food insecure graduate students is also growing. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of doctorate-holding food stamp recipients tripled, according to a 2012 Chronicle of Higher Education analysis. The number of food stamp recipients with a master’s degree wasn’t found to have tripled over the same time frame, but it got remarkably close, going from 101,682 to 293,029. At one large research school, Michigan State University (MSU), the on-campus food pantry reports that more than half of its clients are graduate students.

Ying Liu, a doctoral student in chemical engineering and occasional client of the MSU Food Bank, told msnbc that MSU undergraduates are more likely to be able to call on their parents and other sources of financial support when necessary. Graduate students tend to have less of a safety net. At the same time they’re likelier to have dependents of their own, who they often need to support on a meager stipend.

“A lot of students who are married, they have to support their children,” said Liu. “Because their family is dependent on them. For one person it would be fine, but for a three or four-person family it’s pretty high pressure.”

Kristin Sewell, an anthropologist and doctoral student, is currently raising a teenage son while pursuing a five-year fellowship at MSU. Her daughter, who recently turned 20, is in college herself. Sewell told msnbc that her modest fellowship stipend is enough to ensure that she doesn’t access the MSU Food Bank regularly, although she has used it “when things got particularly tight.”

“Like after my first winter here in Michigan, I hadn’t anticipated my heating bills would be as high as they were,” she said. “I knew they would be high, obviously, but I hadn’t planned for $500 electric bills. So then I decided to use the food pantry just to make ends meet.”

Her decision was shaped in part by her own upbringing.