This column is part of “The State of America,” an msnbc.com series leading up to President Barack Obama’s 2015 State of the Union Address on Tuesday, Jan. 20. This is the state of the issues you care about, as told by organizations promoting social change and other policy experts.

When President Obama turns to the economy in this year’s State of the Union speech, I’m confident you’re going to hear more confidence. The familiar two-step may well become a one-step.

Let me explain. Since he took office, Obama’s discussion of the economy has always had two parts: explain how things are getting better but quickly pivot to how they’re not good enough. We’re moving down the right path, but we’re not out of the woods yet.

That’s been a perfectly reasonable and accurate framing of the issue, of course. The quarter before he took office, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) cratered more than 8%. The first quarter he was president, we lost over two million jobs. Shortly thereafter, due in part to measures he and his team passed and implemented, along with some heavy lifting by the Federal Reserve, the economy was growing again (GDP growth turned positive in the middle of 2009). Employment losses grew smaller and by late 2010 we were adding jobs.

%22Take%20it%20from%20a%20guy%20who%20was%20a%20White%20House%20economist%20back%20then%20%E2%80%94%20people%20really%20don%E2%80%99t%20want%20to%20hear%20about%20how%20%27it%20coulda%20been%20worse.%27%22′

But “getting better” is not “healed.” And take it from a guy who was a White House economist back then — people really don’t want to hear about how “it coulda been worse.”

Obama’s State of the Union addresses have always reflected this duality. It 2010, we heard how the economy’s getting better but it’s still bad; in 2011, it was better for profits and the stock market but not for average folks, in 2012 the economy was getting stronger but not strong enough, and so on.

This year, we may well hear something different. In recent speeches, the president has hedged a lot less on economic conditions. “American resurgence is real. Don’t let anybody tell you otherwise” is how he put it the other day.

I guarantee you, this doesn’t mean President Obama thinks everything’s fine for the broad middle class, as I’m sure we’ll hear on Tuesday night. I believe he meant it when he said a few months ago that the “defining challenge of our time” is “making sure our economy works for every working American.”

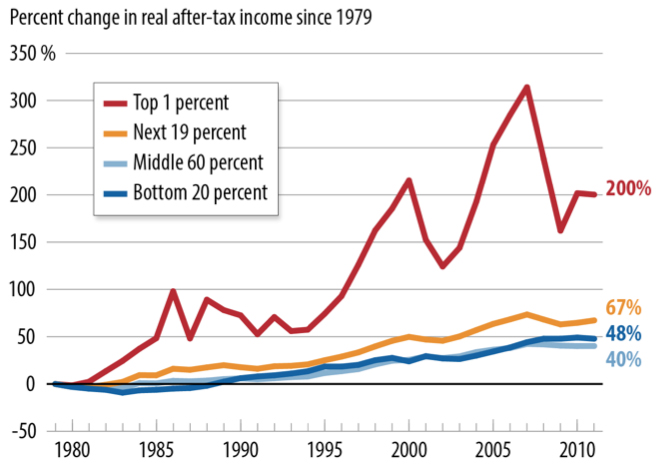

A couple of strong quarters of GDP and job growth can’t fix that. We have a long-term, structural inequality problem, such that we cannot count on overall growth to reliably lift the middle class and the poor. Since the recovery began in mid-2009, real GDP is up 13%, the stock market has doubled in value (again, in real terms), but median household income is flat.

How do we square that fact with claims about an “American resurgence”?

To answer the question, we must distinguish between structural and cyclical. Economies trundle along in two broad frequencies. Shorter-term, cyclical movements yield periods of recession and expansion. Unfortunately, when the expansions mostly reach the top 1%, it’s not easy for the average person to tell the difference. We squirrely economists even had to invent a new term: jobless recoveries, where GDP is growing but employment is not.

But while it took far too long to get there, in no small part due to some bone-headed austere fiscal policies, the president can confidently assert that the U.S. economy is reliably growing. Especially compared to almost every other economy out there, we’re posting solid growth and jobs numbers.

That could change of course, and we’ve still yet to close all the gaps that developed during the Great Recession and initially weak recovery. But in a cyclical sense, the state of the US economy looks good.

That’s the cycle. What’s the structural story? Here we’re talking about long term economic trends that persist throughout the ups and downs of the cycles. And there’s no question that economic inequality is structurally embedded in the U.S. economy. A good way to see that is to look at this graph (above) from an inequality presentation by Ben Spielberg and me. The income of the top 1% takes temporary hits as part of the boom-and-bust cycle, but the trend shows them clearly pulling away from the rest.