%22First%2C%20the%20probable%20cause%20of%20AIDS%20has%20been%20found%3A%20a%20variant%20of%20a%20known%20human%20cancer%20virus.%20Second%2C%20not%20only%20has%20the%20agent%20been%20identified%2C%20but%20a%20new%20process%20has%20been%20developed%20to%20mass%20produce%20this%20virus.%20Thirdly%2C%20with%20the%20discovery%20of%20both%20the%20virus%20and%20this%20new%20process%2C%20we%20now%20have%20a%20blood%20test%20for%20AIDS.%20With%20a%20blood%20test%2C%20we%20can%20identify%20AIDS%20victims%20with%20essentially%20100%25%20certainty.%22′

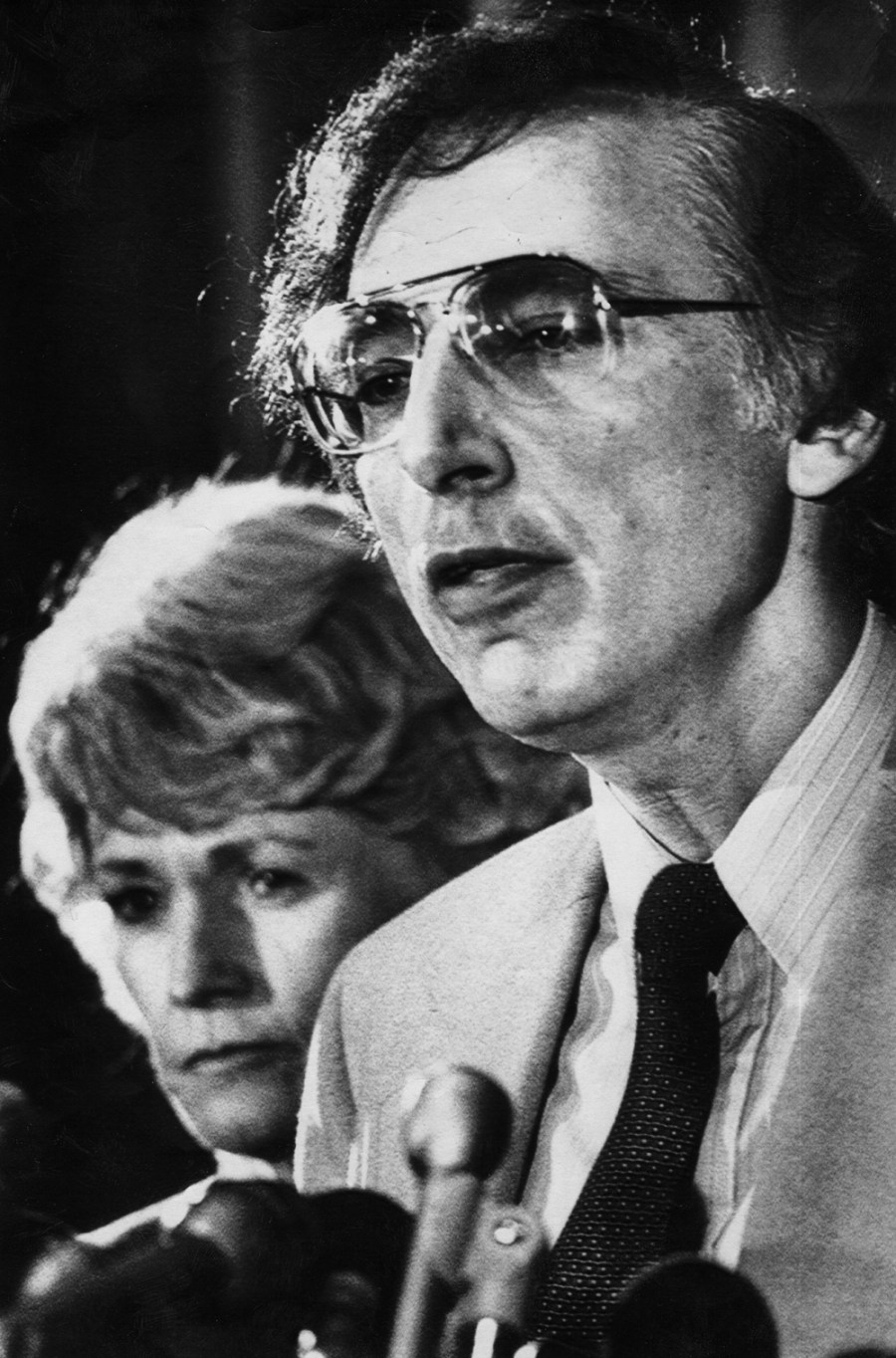

That was Margaret Heckler, President Ronald Reagan’s Health and Human Services Secretary, rocking the world 30 years ago this morning. Her hastily arranged press conference was full of blunders—she jumped the gun by several weeks because of a press leak, claimed U.S. credit for what was partly a French discovery, misidentified the newly discovered virus, and predicted that a vaccine would be ready within two years (we still don’t have one). Yet the announcement had epochal impact. It revealed the source of what would soon become one of the worst plagues in human history, and it sparked scientific and social revolutions that are still playing out today.

Three years earlier, in the spring of 1981, a ghastly new disease had exploded in the gay communities of New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. It eviscerated people’s immune systems, allowing normally harmless pathogens to consume them. Though initially dismissed as a “gay plague,” it had begun killing hemophiliacs and injection drug users, as well as their partners and newborns, and it was spreading worldwide.

PHOTO ESSAY: Treating AIDS around the world

The cause was still a mystery, and ignorance was fueling fear and stigma. San Francisco cops had started wearing masks and gloves to shield them from gay men, and right-wing commentators were shaming the afflicted for their wickedness. “The poor homosexuals,” Pat Buchanan wrote in the New York Post in 1983. “They have declared war on nature and now nature is exacting an awful retribution.”

A 1983 New York Times story captured the growing sense of helplessness. “In many parts of the world,” wrote medical correspondent Lawrence Altman, “there is anxiety, bafflement, a sense that something has to be done—although no one knows what—about this fatal disease whose full name is Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome and whose cause is still unknown.”

By isolating the culpable virus, and developing a reliable test for it, researchers had suddenly cleared a path from superstition to reason. Almost overnight, the discovery helped scientists explain how AIDS spread and how it did not. It enabled rich countries to secure their blood supplies and reduce hospital infections. And though science has yet to produce an effective vaccine, it has made the infection survivable. The first anti-HIV medication, a failed cancer drug called AZT, reached the market in 1986, and by 1996 a three-drug cocktail had turned a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition.

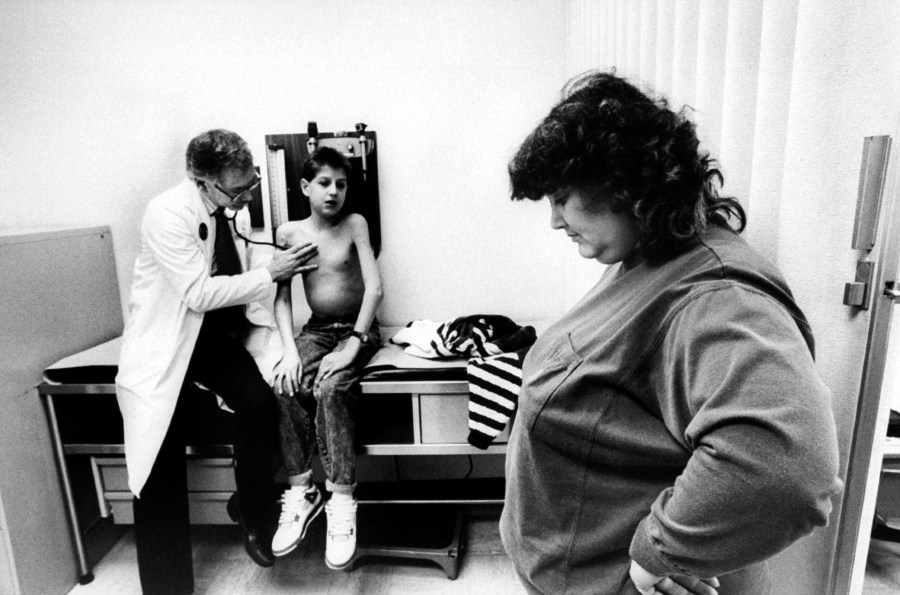

The science advanced swiftly, as researchers elucidated HIV’s structures and survival strategies, but public attitudes evolved slowly. Fear and ignorance reigned for years (the Ryan White saga is but one memorable example). And as science spawned new tools for prevention and treatment, rich countries kept the benefits largely to themselves. Congress and the NIH spent $10 billion a year on the domestic response during the 1990s, while largely ignoring a burgeoning global crisis. From 1996 to 2000, annual AIDS deaths declined by nearly 60% in the United States (from 38,000 to 16,000). Yet the global toll rose by the same proportion during that period, growing from 1 million to 1.6 million a year.