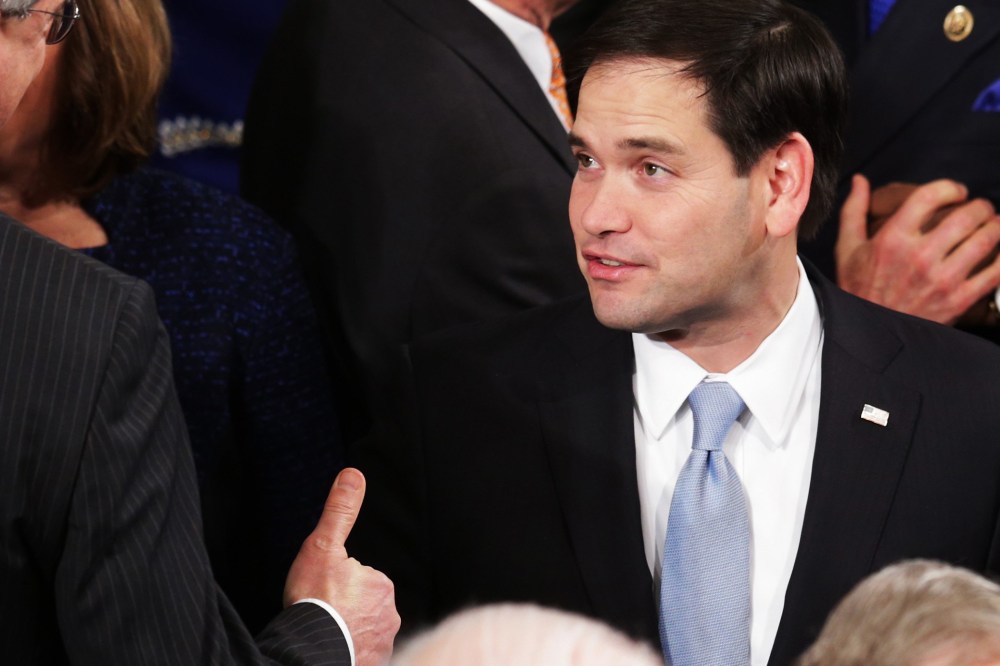

Florida Sen. Marco Rubio says he’s still choosing where to go in 2016: The Senate or the White House. But one thing that definitely won’t be coming with him is his old immigration bill.

“Both of those avenues have their own set of opportunities that are alluring, but ultimately I know I need to make a decision in due time if I want to be able to mount a credible campaign for the presidency — which I believe we can do irrespective of who else is in the race,” Rubio, a Republican, told reporters on Wednesday at a breakfast hosted by the Christian Science Monitor. Rubio reiterated that he will not seek re-election in the Senate if he commits to a presidential run.

Rubio co-authored the bipartisan immigration bill that passed the Senate in 2013, but the move whipped up a backlash from the right and his position in 2016 primary polls has never recovered. These days, he believes that “tactical reality” calls for increasing border security, opening up more immigrants to deportation, and cracking down on employers who hire undocumented workers before moving onto any legislation that would allow undocumented immigrants to stay in America.

“I’ve never believed that somehow we need to do immigration reform in order to win an election,” Rubio said. “On the contrary, I’ve always seen the potential pitfalls politically for someone to get involved in the issue and I’ve experienced it myself.”

%22Ultimately%20I%20know%20I%20need%20to%20make%20a%20decision%20in%20due%20time%20if%20I%20want%20to%20be%20able%20to%20mount%20a%20credible%20campaign%20for%20the%20presidency.%22′

Asked how he might distinguish himself from governors like Scott Walker of Wisconsin or longtime political ally Jeb Bush who served two terms as governor of Florida, Rubio indicated his experience on foreign policy would give him an edge.

“I think for governors that’s going to be a challenge, at least initially, because they don’t deal with foreign policy on a daily basis,” Rubio said.

Rubio’s candidacy, along with Bush’s, would be heavily tied to immigration reform, an issue where both have broken with many in their party to demand a path to legal status for undocumented immigrants.

“I think that most people understand that most of them are going to be here for the rest of their lives,” Rubio said.

The increasingly hardline GOP looks eager to oblige Rubio’s enforcement-first approach. This month, the Republican-controlled House passed legislation to undo a new move by President Obama to protect up to five million undocumented immigrants from deportation, halt a similar 2012 program for DREAMers — immigrants brought to the country as children — and forbid immigration authorities from prioritizing criminals for removal over otherwise law-abiding immigrants. Twenty-six House Republicans broke with their party on the DREAMer portion of the bill, but Rubio said he believed the program, known as DACA, should not accept new applications and eventually expire altogether.

After Romney lost in 2012, thanks in part to disastrous margins with Latino voters in states like Florida, Rubio warned Republicans that voters would not listen to the party “if they think you want to deport their grandmother.” On Wednesday, however, he told reporters he objected to the idea the party’s recent deportation push jeopardized their standing.

“I don’t agree that Hispanics view that position as hostile,” Rubio said. “This notion that somehow Hispanics don’t want the law enforced or law to exist on immigration less than the general population is not true.”