When the votes are tallied in Virginia’s race for governor on Tuesday, over 300,000 citizens will be missing from the voting rolls — including 20% of the state’s black population. The reason is not low turnout or voter ID, but a growing and often invisible barrier to voting that is upending elections around the country.

Over 5 million Americans are barred from voting because they have criminal records, according to a report this year from the Sentencing Project.

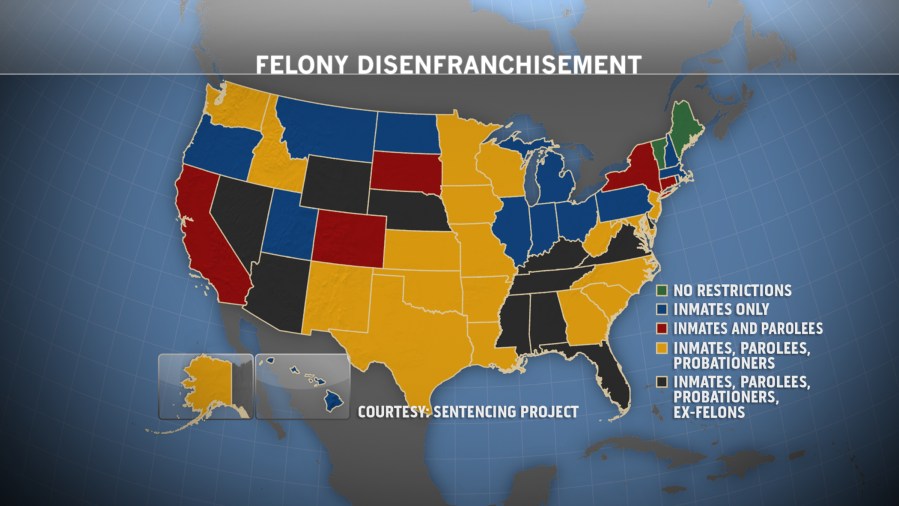

The crackdown on ballot access is so intense, a majority of states actually bar former convicts from voting even after they are released from prison.

If voting rights were restored to those former inmates, about 4.3 million more Americans would be able to vote. That is over three times margin of victory in the last House midterm elections.

“You have this chunk of voters that’s not there,” explains NBC News political director Chuck Todd. “When you see the decisions that have been made on this issue — and a lot of voting access issues — it’s clear that political partisans are operating on what’s best for their own party’s cause, period,” says Todd.

Researchers have found that restrictions on voting by ex-felons “tend to take more votes” from Democrats – and that universal suffrage could change the outcome in Senate and presidential elections.

Focusing only on the electoral impact, however, can distract from the fundamental rights at stake.

“If you care about this issue – and you believe this issue of felony rights is about full restoration of rights after you’ve paid your penalty to society,” says Todd, “then [put aside] these studies. Who cares the political impact – it shouldn’t matter.”

Some politicians are coming around to that view as well, criticizing the crackdown on voting rights regardless of the potential effect on their party.

The color line

“If I told you that one out of three African-American males is forbidden by law from voting, you might think I was talking about Jim Crow 50 years ago,” said Sen. Rand Paul at a Senate hearing last month. “Yet today,” Paul lamented, “a third of African-American males are still prevented from voting because of the War on Drugs.”

Likening today’s felony voting laws to the racist oppression of the former confederacy is an especially resonant criticism from Paul, a Kentucky Republican and popular Tea Party figure. It also echoes a concern of many scholars and civil rights advocates – that these policies reflect a drive to incarcerate and politically marginalize black Americans.

“The states that have the harshest policies just happen to be those states with legacies of slavery, segregation, discrimination, voter suppression and the denial of the right to vote,” National Urban League President Marc Morial told MSNBC.

Law professor Michelle Alexander presses a similar point in her bestselling 2010 book, The New Jim Crow. While the nature of “racial exclusion” in American law has visibly changed, she suggests its “outcome has remained largely the same.” A large percentage of “black men in the United States are legally barred from voting today,” she writes, “just as they have been throughout most of American history.”

That is especially true in the South — laws in just six southern states serve to disenfranchise over half of the ex-felons barred from voting across the country.

Alexander cites such restrictions as part of a spike in putatively “colorblind” policies that function to criminalize, segregate and effectively disappear many minorities. “Today it is perfectly legal to discriminate against criminals,” she stresses, “in nearly all the ways that it was once legal to discriminate against African Americans.”

It is also relatively easy, since convicts are not politically popular to advocate for, and, thanks to felony disenfranchisement, are largely barred from politically advocating for themselves.

Jean Chung, a researcher at the Sentencing Project, found that Black Americans over 18 years old are disenfranchised at “a rate more than four times greater than the rest of the adult population.”

Restricting felony voting naturally perpetuates racial disparities at earlier steps in the criminal justice process, from presuming the guilt of blacks by disproportionately profiling and policing them, to punishing black drug defendants more harshly than white defendants.

It also reflects the explosion in the number of Americans incarcerated during the war on drugs. Over the 30 years since drug punishments were increased in the 1970s, the prison population more than quadrupled – with the U.S. besting Russia and China for the highest incarceration rate in the world. In 1976, felony disenfranchisement laws barred about 1.2 million Americans from voting – a sliver of the 5.5 million barred from voting today.

For the first time in a generation, the prison population began declining in 2010, reflecting a gradual shift away from harsh incarceration policies.

While that shift does not automatically restore the rights of any Americans who have already been to prison, the backlash to the war on drugs is nudging the politics of the issue.