*This post has been updated to reflect Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s declaration Tuesday to take “no action” on any Supreme Court nominee.

Just hours after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia was confirmed, the spotlight was already divided by political posturing on all sides — and that is where public attention has largely remained.

“What is less than zero? The chances of Obama successfully appointing a Supreme Court justice to replace Scalia,” said a spokesman for Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), who sits on the Senate Judiciary Committee. “I plan to fulfill my constitutional responsibilities to nominate a successor in due time,” President Obama said the same day. A little more than a week later, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell pledged that the Senate would not hold a hearing on any nominee President Obama might put forward.

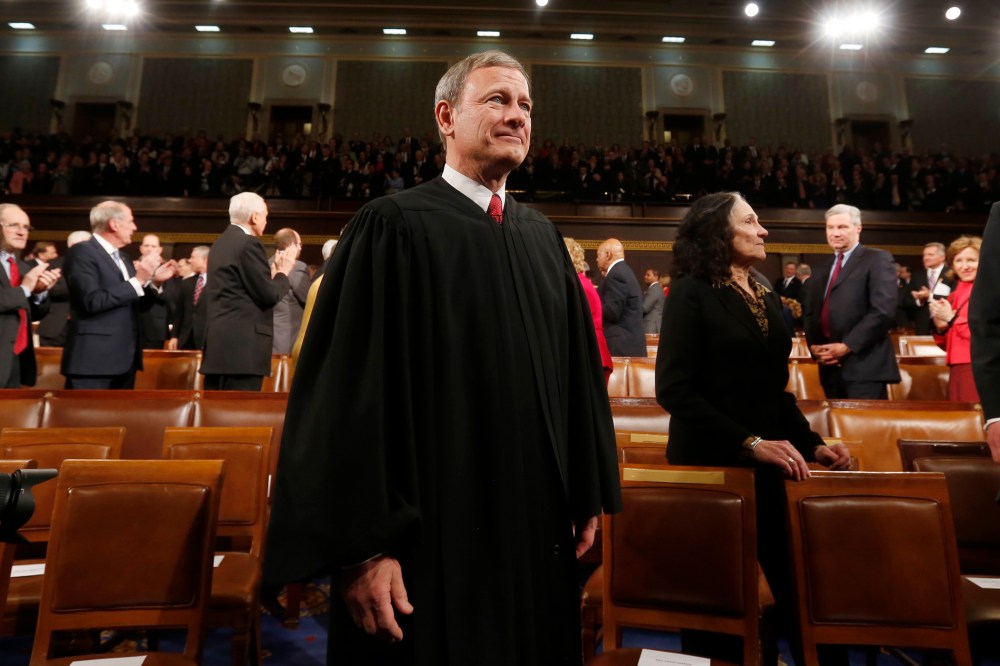

But the person who may have the most to lose in the long run from an enduring Supreme Court vacancy is not the president or Senator McConnell. It is Chief Justice John Roberts. Other than to release his own statement grieving the loss of his colleague, Roberts has been silent on the issue of a new nomination. But it is his court’s legacy that hangs in the balance.

The court’s value — this is the “Roberts Court,” after all — depends on its ability to adjudicate disputes. With the record-setting snarl both in Congress and between the legislative and executive branches, Supreme Court decision-making has become the ultimate tool of power in our democracy. When the court fails to function, so too does our government as a whole.

An empty seat on the court leaves open the possibility for numerous 4-4 ties on crucial national issues ranging from immigration to voting rights to abortion, leaving a series of often contradictory lower court rulings on these matters intact and rendering the Supreme Court less than supreme.

Thus Roberts has an important — and not unprecedented — role to play in ensuring the continued legitimacy of his court. One need only to look to history to understand this responsibility.

In 1937, as President Franklin Roosevelt was trying to pack the court with justices favorable to his New Deal programs, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote a letter to the U.S. Senate stating his objection to the president’s proposal, which would have needed the Senate’s consent. “The present number of justices,” i.e., nine, “is thought to be large enough so far as the prompt, adequate and efficient conduct of the work of the court is concerned,” Hughes wrote, aiding the effort to thwart Roosevelt’s plan.

While it follows that the current roster of eight justices would not be “large enough” to conduct the work of the court, the larger point here is that the understated involvement of a chief justice had broad implications for the direction of the court and might occur in a way that retains the decorum of the office.

Roberts could take a page from Hughes and draft a public statement or letter, maybe reiterating Justice Anthony Kennedy’s 2012 rebuke that the current confirmation process, a political tennis match played out in the press, is “bad for the legal system, [making] the judiciary look politicized when it is not, and it has to stop.”