New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio took office this year with a mandate to rewrite what he called a ‘tale of two cities’ left by his billionaire predecessor, Mike Bloomberg. Among other things, he promised to curb the expansion of charter schools— privately run public schools that Bloomberg and big-money Wall Street donors have championed.

But just 11 weeks into de Blasio’s mayoralty, a series of public relations missteps and what some see as political miscalculation around charters have not only pitted him against his friend and mentor, Democrat Gov. Andrew Cuomo, but also against throngs of parents from the communities of color the mayor promised to uplift.

National Democrats had all but anointed de Blasio the prince of a new era of progressive politics, and are watching to see if his broader blueprint for America’s largest city could be successful and replicated across the country.

But as de Blasio pushes forward and absorbs the bruising of scrap-it-out New York politics over his education policy, the question remains: what’s at stake for the national progressive movement? And will the charter school debate, rife with the sticky politics of race and class, be the undoing of New York City’s grand progressive experiment?

“This isn’t just a New York City story or a regional story. This really is a national fight that’s going on between a growing progressive wing of the party and corporate Democrats of the party,” said Mike Lux, president of American Family Voices, a national advocacy group.

Lux called de Blasio’s election a “huge plus” for the national progressive community, who are keeping a close eye on the charter school controversy.

“The issue itself is reverberating around the country,” Lux said. “Do we want true public education and the resources to be invested in making public school better or do we want to siphon it off to the next hedge fund guy who wants to open a new charter school?”

At issue is de Blasio’s decision not to allow some charter schools to co-locate with traditional public schools in city-owned buildings. Both friends and foes have filed lawsuits, the former claiming the mayor is taking opportunity away from poor minority charter school students and the latter claiming he didn’t go far enough to stop the expansion of charters.

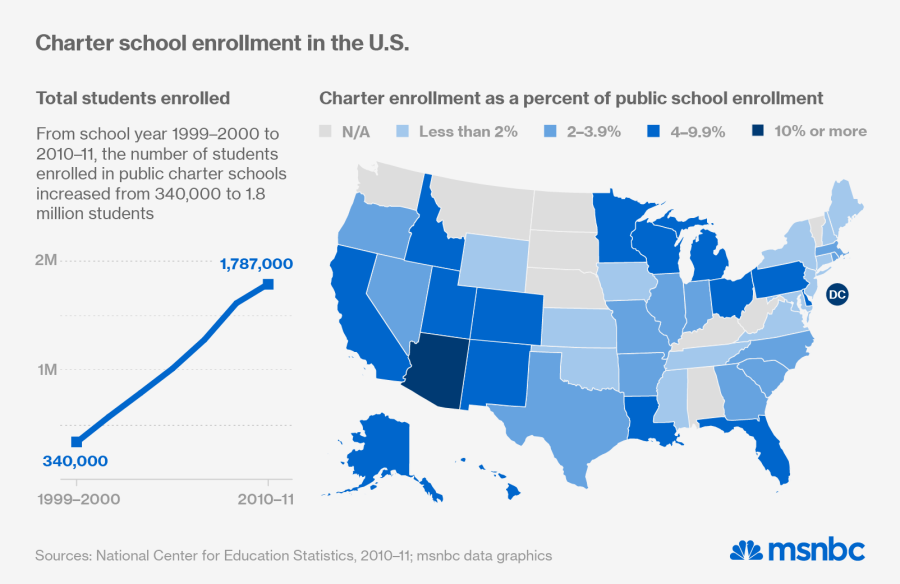

Charters had flourished for the better part of a decade under the Bloomberg administration, which offered the schools unprecedented access to city-owned buildings, including rent-free space.

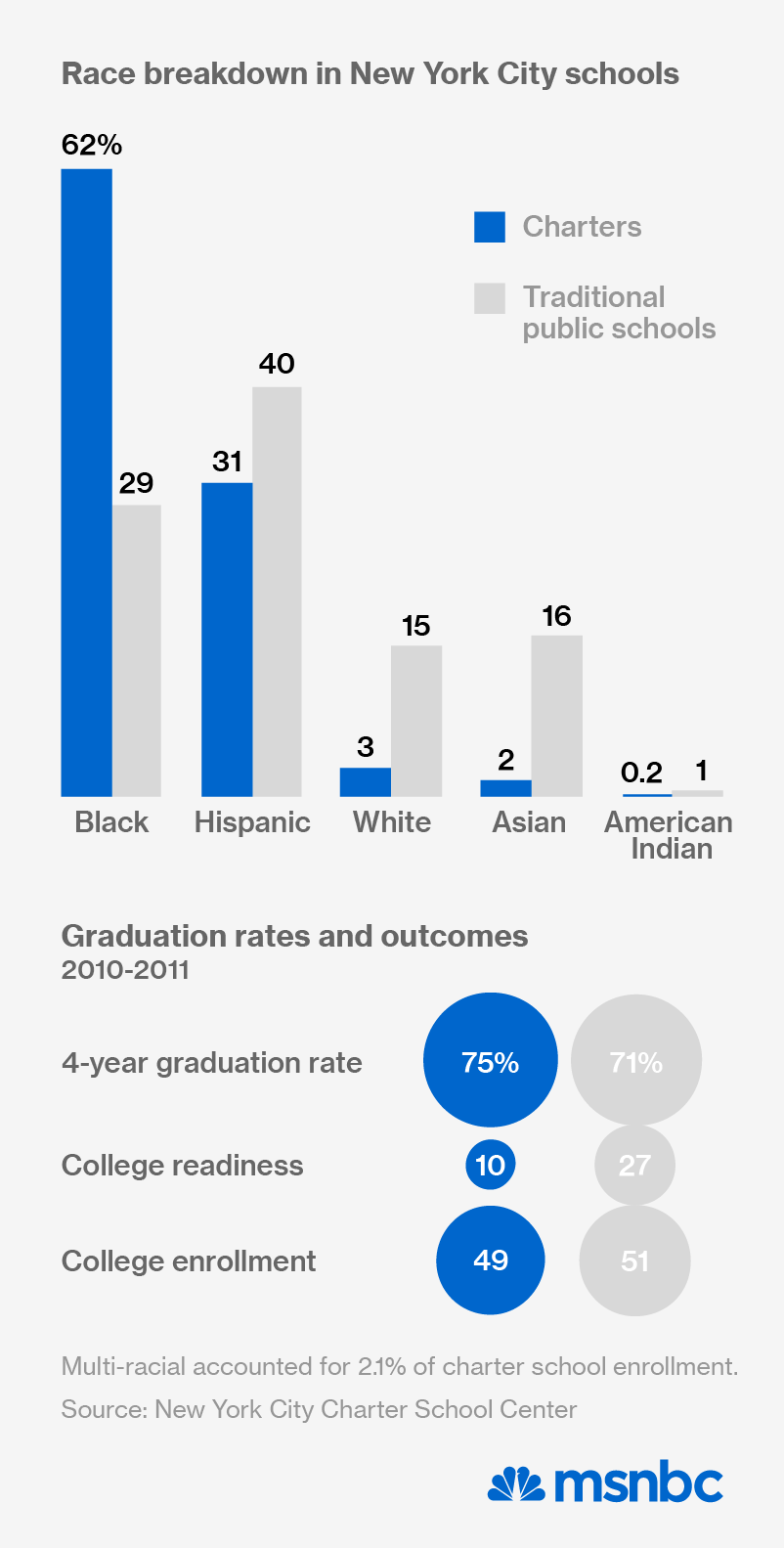

Targeting charter schools, which educate about seven percent of the city’s 1.1 million public school students, seemed a practical and prudent political move. By aligning himself with the mostly black and Latino public school families and teachers unions who’d long complained that resources were being diverted from neighborhood schools to charters, de Blasio sought to bolster the populist cred that swept him into office.

Instead, de Blasio has sparked a firestorm by choosing to stop three of eight charters run by a political nemesis from opening in public school buildings, overruling a decision made in the waning days of the Bloomberg administration. Co-locating the schools, de Blasio said, would in one case displace special education students and in the two others would’ve housed elementary and high school students under one roof.

Despite allowing the vast majority of the charter schools approved by his predecessor— 36 of 45— to open as planned, the negative reaction to de Blasio’s decision was swift and well-organized.

Thousands of mostly black and Latino students and their parents have rallied in support of charters. Millions of dollars have been spent on TV ads attacking the mayor. And Cuomo came out publicly in support of the mayor’s chief rival in the debate, Eva Moskowitz, a former New York City councilwoman who runs the Harlem and Bronx-based Success Academies, the city’s largest and most successful network of charter schools. The vast majority of her students are black and Latino.

In one television spot, a narrator says de Blasio is taking away “the hopes and dreams” of students, as a collage of smiling black and brown children in school uniforms fades from the screen.

“Mayor de Blasio, don’t take away our children’s future,” the ad continues.

The uproar hit an apex when de Blasio and Cuomo appeared at dueling rallies in Albany, the state capital. Cuomo, a self-styled centrist running for re-election this year, joined Moskowitz at the pro-charter rally, sending a not-so-coded message to de Blasio, who was headlining a much smaller rally down the street.

“You are not alone,” Cuomo boomed. “We will save charter schools.”

During his campaign, de Blasio said that Moskowitz and her schools have had a “destructive impact” on public education and that it’s time for her to “stop having the run of the place.”

“It wouldn’t happen if she didn’t have a lot of money and power and political privilege behind her and if Department of Education didn’t say ‘yes ma’am’ every single time and that’s going to end when I’m mayor,” de Blasio said.

Charter schools have been both praised for offering parents additional educational choices, and decried as an instrument of conservatives and the anti-union set to try to break the back of teachers unions. Democrats have long had a stronghold on union support, and the growth of non-union charter schools has slowly pried at that grip.

“This is one more time where the charter movement has been hijacked by some conservatives who want it to be a competitive system and who want to help some kids at the expense of others,” said Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers. “Our goal is to help all kids.”

Moskowitz has filed a lawsuit against De Blasio, claiming that the civil rights of her students who were enrolled in the three charter schools barred from locating in public schools, have been violated.

The war of words (and policy) over charter schools has proven a thorny issue for de Blasio, in a city where the majority of public school students are black and Latino and where families have fought desperately for access to quality education. New York City, in particular Harlem and the Bronx, is ground zero in the broader fight over charter schools and is the national exception in terms of academic performance.

Across the country most charter schools perform no better or worse than their traditional public school counterparts. But in New York City, charter schools typically perform at or above the same level of neighborhood schools.

Jeffrey Henig, chairman of the Department of Education Policy and Social Analysis at Columbia University, said it’s too early to say whether the hits de Blasio has taken in recent days is a signal of anything other than politics as usual.

“It’s inevitable that he’s going to lose some of the aura of being sort of the new national progressive leader. You can’t come in and run a big complicated city like New York and not have to make some comprise over time and negotiate,” Henig said. “That initial high was destined for some come down no matter what.”