A high-level commission formed to address the underlying causes of the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, met Monday for the first time — a week after news that a grand jury would not indict Officer Darren Wilson for the killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed local teen.

The Ferguson Commission’s first formal sit-down reflects a shift in focus, as attention moves away from the legal process involving Wilson and toward addressing the economic, social, and educational issues that the controversy has brought out.

RELATED: Tackling the deeper issues in Ferguson

Monday afternoon’s event, which was open to the public, began with a briefing from Rev. Tommie Pierson, a local pastor, and included a review by Missouri Assistant Attorney General Patricia Churchill of the rules governing the commission.

“More than anything else, the eyes of our region, neighbors friends, families, church members are upon us,” Rev. Starsky Wilson, a co-chair of the panel, told the audience. “Our work will affect their life outcomes first and foremost.”

“We know that solutions can be found,” said the other co-chair, Rich McClure, a former aide to one-time Missouri senator John Ashcroft. “And we can’t expect others to change if we remain the same.”

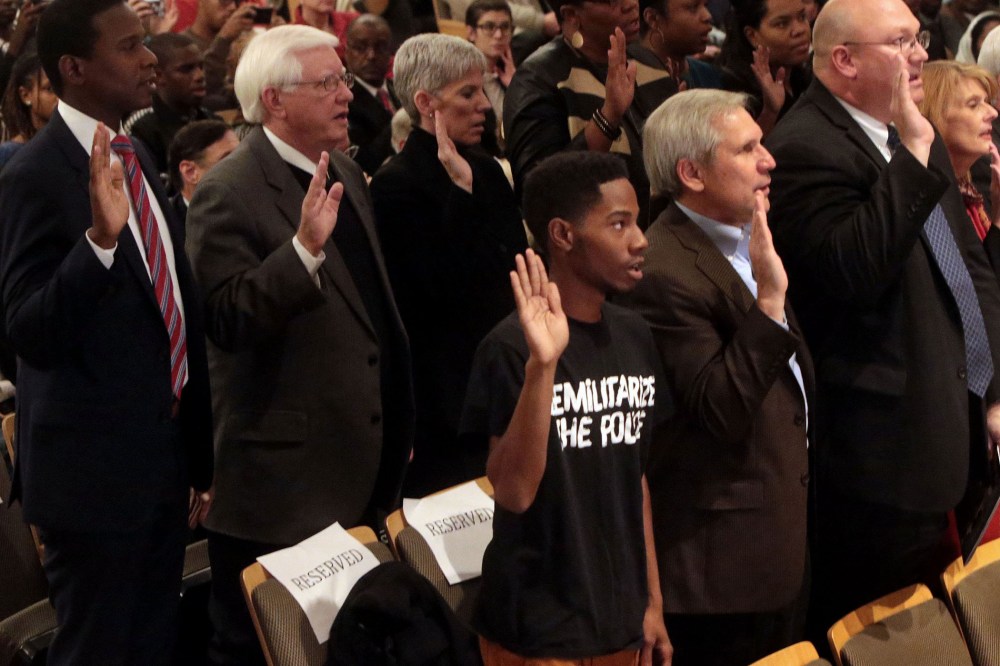

All 16 of the panel’s members — who come from government, academia, law enforcement, business, and even the protest movement — attended. Brittany Packnett, the CEO of St. Louis’s Teach for America office, and Rasheen Aldridge Jr., a youth activist leader, attended portions via phone, since they’re in Washington D.C. for a separate White House meeting on Ferguson, said Allison Collinger, a spokeswoman for the commission.

Both Packnett and Aldridge recorded video statements that were played at the meeting.

“Young people can one day feel like once they walk up and down these streets that they’re not harrassed and that they’re not targeted every single day just stepping outside their community,” Aldridge said. He admitted he was at first “hesitant” to serve on the panel because many young people have been skeptical of state and local leaders’ decisions since the controversy began.

RELATED: In Ferguson, a failure of leadership

Said Packnett: “There is no zip code, no race, no background that should determine any of our outcomes, and so in order to make sure that that happens, I need to play my part and make my contribution.” Other commissioners made in-person statements about why they were serving.

But some members of the public expressed skepticism about the commission in written comments that were submitted later in the meeting.