Democrats in tight races have found a new villain this election cycle: student debt.

“It totally limits your options of what you can do,” said one student in an ad from Kentucky U.S. Senate candidate Alison Lundergan Grimes, who accuses Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of having “turned his back on the students” for blocking Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s student loan refinancing bill.

“New Hampshire students leave college with an average of $33,000 in debt—it can slow them down for years,” said Sen. Jeanne Shaheen in another campaign ad supporting Warren’s bill.

“It’s supposed to mean the sky’s the limit. But for this generation, attending college too often results in skyrocketing debt,” said Hawaii’s Sen. Brian Schatz, in the weeks before a tight Democratic primary.

With student loans topping a record $1 trillion last year, Democrats also argue is that skyrocketing debt is not only hurting individual borrowers but the entire economy along with it. “And by the way, this is one of the biggest things hurting the housing market. When a family — age 32, 31 — has all these student loans, they’re not going to buy a mortgage,” Sen. Chuck Schumer said at a May hearing.

“Wisconsin students have everything it takes to compete for the jobs of the future, but we need to be doing everything we can to reduce the financial burden that they graduate with,” said Mary Burke, the Democratic candidate challenging Gov. Scott Walker, who’s put student loan reform at the heart of her jobs plan. “More money in the pockets of Wisconsin’s students and families also means more money being spent in Wisconsin’s economy.”

But the long-term economic impact of rising student loans is more complex and ambiguous than the political rhetoric suggests—and the Obama administration has acknowledged as much as well.

A college degree still pays major dividends to both individuals and the economy as a whole. “A four-year degree yields approximately $570,000 more in lifetime earnings than a high school diploma alone, while a two-year degree yields $170,000 more,” Deputy Treasury Sarah Bloom Raskin said this week, according to prepared remarks.

While noting that student debt has “become a serious burden for far too many borrowers, Raskin argues that “student loan debt is not inherently bad, until it becomes too costly to propel people to a place they could not reach without it; until the investment cannot pay off at both the individual and societal level.”

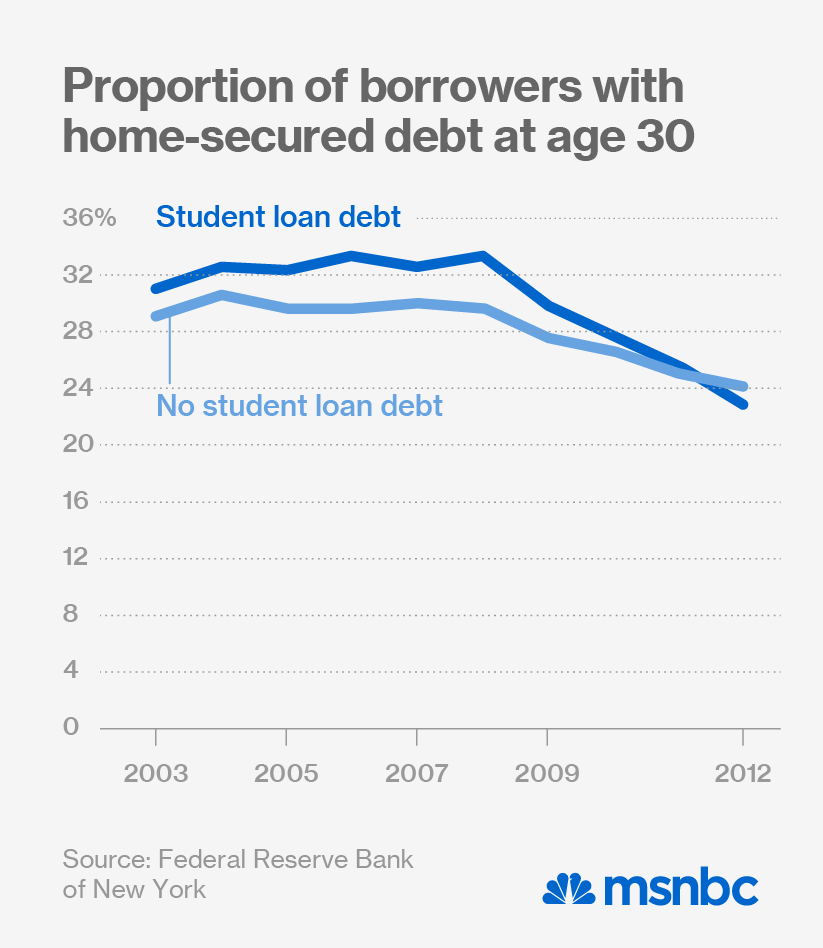

The returns on such investment have been slower to come by since the housing bust. Young people with student debt actually used to be more likely to buy homes, as they were likely to be more highly educated and in higher paying jobs. In recent years, the opposite has held true: “Now, for the first time in at least ten years, 30-year-olds with no history of student loans are more likely to have home-secured debt than those with a history of student loans,” the New York Federal Reserve bank said in a 2013 study. A similar trend holds true for auto loans.

That said, it’s unclear how strongly these developments are due to student debt, and how much is due to a weak labor market that’s preventing young people from benefiting from their investments in their education. Student debt “has some effect on the economy but it’s outweighed by other factors—the job market and stagnant wages are far more important for the economic growth and the housing market,” says Cristian DeRitis, senior director of Moody’s Analytics.

The total number of student borrowers has grown in recent years, along with the outstanding debt load per borrower, which increased from $21,000 in 2007 to $25,000 in 2012, according to the New York Fed. But the outlook has begun to improve as the economy has turned around as well. “Total federal originations have fallen since their 2012 peak and originations per borrower have fallen since 2010,” said Treasury’s Raskin notes. “If these trends continue as the recovery strengthens further, they may noticeably slow the growth of outstanding student loan debt.”

Not all the headline-grabbing stories on student debt take other economic and social factors into account. A new study from John Burns Real Estate Consulting estimates that student debt will prevent more than 400,000 home purchases from happening in 2014. But the study doesn’t account for the other factors that are likely to be keeping young potential homeowners out of the market, including the weak job market and an average marrying age that continues to creep higher.

In fact, the rising delay in marriage and having kids “end up explaining the entire decline in homeownership,” says Jed Kolko, chief economist for Trulia, a housing research and real estate site. “Young adults are equally likely to own a home as young adults twenty years ago with the same demographic.”