It’s no secret that kids are the cigarette industry’s lifeblood. The vast majority of the world’s smokers get addicted before turning 18, and one in four starts before age 10. If tobacco companies relied on mature adults to replace the 6 million customers their products kill each year, the businesses would wither in a generation.

The industry steadfastly denies making any effort to recruit new smokers, claiming that its multi-billion-dollar marketing efforts serve only to inform adult users about “the available product range” and “their preferred product choice.” If the recent profusion of candy-flavored tobacco products hasn’t demolished that assertion, Marlboro’s latest promotional blitz should seal the case.

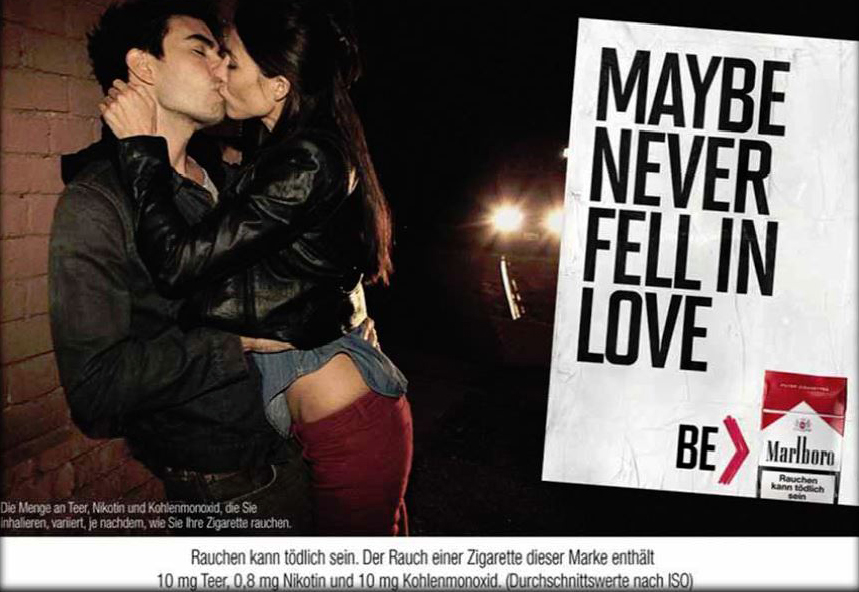

Over the past three years, U.S.-based Phillip Morris International (PMI) has mounted a 50-country campaign to update Marlboro’s image. The iconic Marlboro Man, long dead from lung cancer, has returned in the guise of a romantic, rebellious, thrill-seeking hipster who is everybody’s idol and nobody’s fool. This can be you, the ads assure self-doubting teens, if you take this life-changing pledge: “NEVER SAY MAYBE. BE MARLBORO.”

The campaign has focused largely on low- and middle-income countries, where tobacco sales are burgeoning even as they decline in the United States. The rollout started in Germany, but authorities in Munich stopped it in 2012 after finding that the campaign “specifically targets risk-taking, rebellious youths” and appeals to children as young as 14. While fighting that ruling, PMI has aggressively expanded the campaign in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia, targeting such tobacco-ravaged countries as China, Indonesia and the Philippines.

“Cigarettes should be marketed to adults only, and we take steps that go above and beyond the requirements of the law to ensure that our marketing is directed toward adults,” the company told msnbc. “For example, in Germany, the Marlboro campaign features models that are at least 30 years old. None of our marketing uses cartoons or youth-oriented celebrities.”

Cartoons worked wonders for R.J. Reynolds back in the late 1980s, when a dashing dromedary named Joe Camel served as that brand’s Marlboro Man. Joe shot pool, rode a Harley and jammed on his sax as hot girls eyed him admiringly. In a 1991 study, researchers at the Medical College of Georgia found that nine out of 10 six-year-olds could match the character with Camel cigarettes—nearly the same proportion that could pair Mickey Mouse with the Disney Channel—and the company was shamed into retiring him.

PMI has wisely skipped that ploy, but the campaign’s characters won’t strike you immediately as mature adult smokers evaluating the “available product range.” They wear ripped jeans, skimpy T shirts and funky hats. They play guitars or spin vinyl disks in underground clubs. They kiss passionately on dark, urban side streets. Or they soar above rugged mountain terrain on snow boards and dirt bikes. And unlike comparison shoppers, they never say maybe. “Maybe never wrote a song,” the campaign’s taglines proclaim. “Maybe never fell in love. A maybe never reached the top.” Worse yet, for a vulnerable adolescent, “A maybe is not invited.”

Though PMI denies these are youth-oriented appeals, the company’s own records show it has spent decades courting adolescents. “Because teenagers are uniquely vulnerable to marketing,” a group of seven anti-tobacco groups charges in a recent monograph on the Maybe campaign, “the tobacco industry has spent billions of dollars developing marketing tactics that hook teens and addict them for life.”