SANFORD, Fla. — Police Chief Cecil Smith drew a mix of high-fives and heckles as he walked down the main thoroughfare of Goldsboro, a historic black neighborhood at the heart of this Florida town.

Passersby honked as he strode passed shuttered storefronts and dive bars. Eyes rolled as he made his way by a barbecue joint and a tattered old pool hall. Older women offered smiles while much younger ones turned away.

“I’m praying for you!” one woman yelled out.

Smith took the job as top cop just over two months ago after the previous chief was ousted in the fallout over the killing of Trayvon Martin. Smith, who is black, has made a habit of patronizing 13th Street, which runs through Goldsboro’s core.

“If you have an issue,” he urged residents and shopkeepers, “pick up the phone and call me.”

Smith’s good-will tour down one of the toughest streets in town is meant to allay long-simmering tensions felt between the black community and the police department, whose gleaming $20 million headquarters built in 2010, is located at the top of largely impoverished 13th Street.

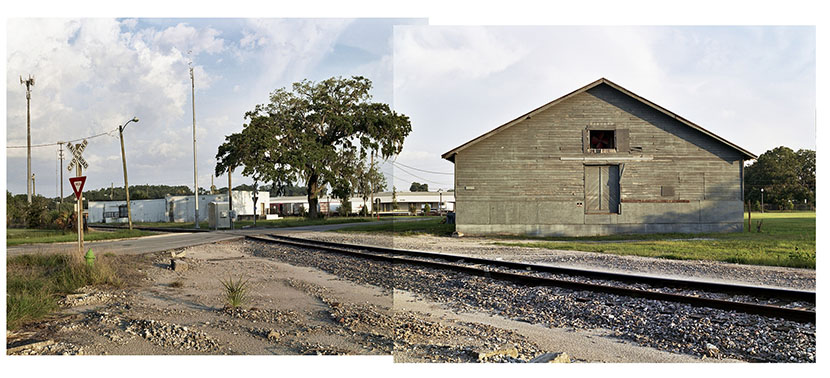

The boulevard is a crumbling shell lined with shuttered storefronts and dimly lit mom-and-pop shops with sparsely stocked shelves. At night, gunfire is common, neighbors say. And the police routinely sweep through to disperse the crowds of young people that pool on street corners and in vacant lots.

It is along this road, the once bustling main drag of what a century ago had been one of the first African -American incorporated towns in Florida, where tensions brewed and then spilled over after Martin’s killing.

And it is here where Sanford’s black community will wait together for the verdict.

Police initially declined to arrest George Zimmerman who claimed he shot the teen in self-defense. Zimmerman is on trial in Sanford for second degree murder and has pleaded not guilty.

Prosecutors say that Zimmerman profiled, followed and then killed Martin on Feb. 26, 2012, as Martin made his way through the neighborhood where his father’s girlfriend lived.

The shooting did not take place in Goldsboro but in a gated community a few miles away. Still, it highlighted a broad gulf between law enforcement and black residents that has widened through the years.

Martin’s killing and the lack of an immediate arrest conjured up memories for Goldsboro of a shooting that took place two years earlier.

In that case, police shot and killed Eugene Scott, a black resident who had been jailed for armed robbery and was a fugitive on other charges. The shooting took place in a grocery store parking lot while police were attempting to arrest him. Scott was shot in the back. The officer who opened fire said he did so after Scott tried to run over his partner. The officer was cleared by law enforcement officials of wrong doing, but many in the black community remained unsatisfied with the findings.

Along 13th Street, residents are following Zimmerman’s trial closely from local bars and over games of dominoes. Some say that what hinges on the outcome of the case is what blacks here have been owed far too long— justice.

“People are trying to use this case to move us forward,” said Pastor Valarie Houston, whose church is on the corner of Olive Avenue and 13th Street. “For this community,” she said, the trial brings “an opportunity for a spiritual awakening as well as a sense of hope and empowerment.”

A hard pill to swallow

On most afternoons, older men take refuge from the biting sun under the palm and willow trees where South Pomegranate Ave. meets W. 13th Street. Many of them spent years laboring in the region’s citrus groves and celery fields but now commune over cold beer and boisterous games of dominoes.

Their leisure time is equal parts fellowship and an informal people’s court where they pass judgment on everyone from local politicians to neighborhood ne’er-do-wells. They trade stories of run-ins with white supervisors and the police.

More recently the often raucous deliberations have been about Zimmerman’s trial.

“I’ll tell you this much. If he’s found innocent there’s going to be an uprising,” said Cecil Nelson. “There’s going to be trouble.”

The collective of men let out a chorus of mm-hmms above the clack-clack of dominoes hitting tabletops.

“I had a 17-year-old son when that boy was killed,” Horace Cain chimed in. “Suppose that was my son. It’s a hard pill to swallow. George Zimmerman is living. Trayvon is dead. That boy’s daddy can’t hug him or touch him.”

Nelson, Cain and most of the others here remember childhoods with segregated public spaces. Most said they still don’t feel comfortable going downtown, where nearly all of the businesses are white-owned and patronized by white residents.

The history of racial strife runs deep in Sanford, founded in 1870 by Henry Shelton Sanford, an American diplomat who served in the Congo. He later argued that the country would be better off if blacks were returned to Africa, according to historian Adam Hochschild in his seminal work, King Leopold’s Ghost.

In 1946 Sanford’s police chief famously forced Jackie Robinson out of a minor-league baseball game, refusing to let him integrate the exhibition. “The Robinsons were run out of Sanford, Fla., with threats of violence,” Robinson’s daughter, Sharon Robinson, later wrote. In 1997 the city apologized for its treatment of Robinson.

During the Civil Rights era, city leaders cemented over Sanford’s lone public pool rather than allow black children to swim in it. While that time has long passed, the town remains largely segregated with the majority of blacks living in neighborhoods such as Goldsboro. About 30% of the city’s 54,000 residents are black and 57% are white, according to the latest Census.

Much of Sanford is the stuff of post cards, with red-bricked streets downtown and a picturesque waterfront. Crooked oak and willow trees hunch over lazy roads. Further away from downtown are the fruits of Sanford’s more recent sprawl, with newer developments similar to the gated community where Martin was killed.

While the city has pumped millions into new projects and redeveloping its waterfront, there’s been little investment in Goldsboro. Many of the streets don’t have sidewalks, the sewer system is in disrepair and the closure of several public housing complexes has left acres of land pocked with shuttered cinderblock apartments and many residents displaced.

“I don’t see how we as leaders could talk about developing Sanford to its fullest potential if you don’t address the needs in the depressed areas,” Velma Williams, the city’s lone black commissioner, told msnbc.

It’s rough out there

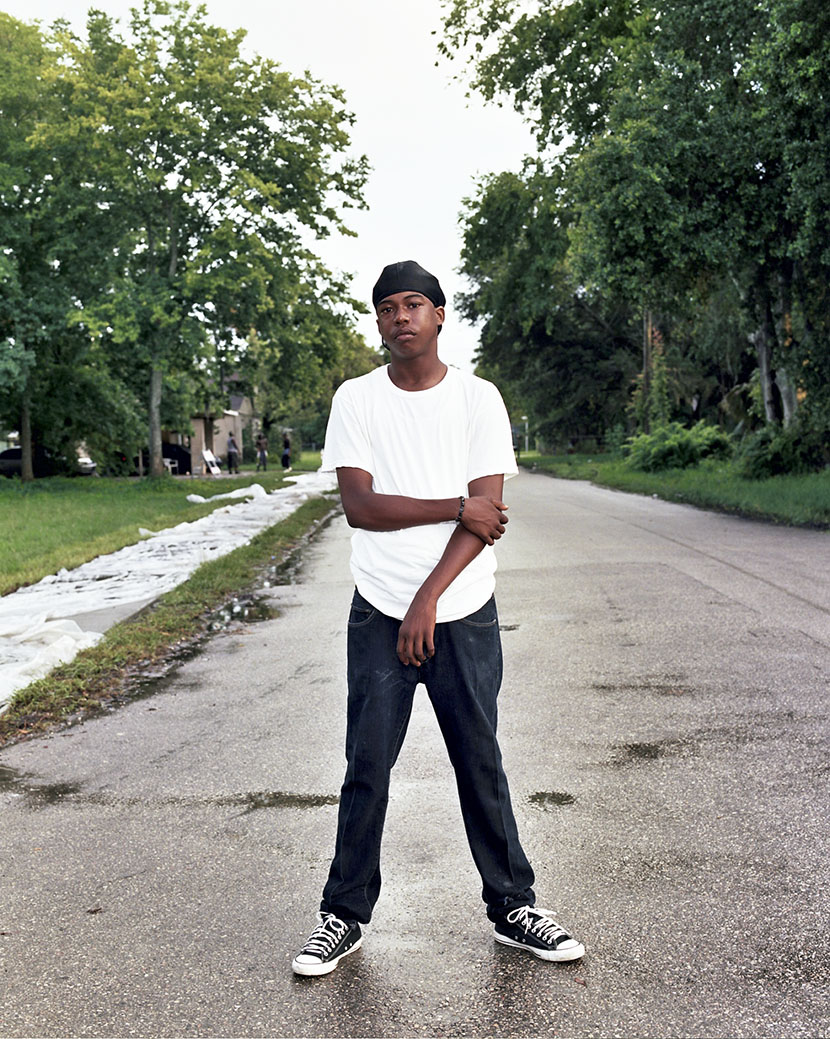

Further down on 13th Street, Juwann McCall, 16, stood on the corner of Oleander Avenue, leaning on a stop sign that marks his slice of the neighborhood.

“It’s rough out here,” said McCall, a slender, somewhat sullen-faced boy, looking anxiously over his shoulder. “You just hope, just hope that you be the one to make it out.”

For months leading up to Martin’s death, residents said there had been shootings between rival groups in the neighborhood. But Martin’s death seemed to affect them in a different way: Martin’s killer wasn’t black. Zimmerman is of white and Hispanic descent.

The deaths of other black men had not led to protests in Goldsboro but McCall joined the neighborhood rallies that followed Martin’s killing. He would stand along busy streets with a pack of Skittles, like the one’s Martin carried that night, holding a sign that read “Honk For Justice.”

A slow trickle of young men walked by and offered head-nods or shouts from across the street.

McCall threw up a hand or shouted back.

“Every day I worry,” he said. “So, just think like, just pray and everything should be okay but like it’s a lot of crazy stuff going on around here and stuff so, I just try to stay out the mix.”

From her little church on the corner of Olive Avenue and 13th Street, Houston says she has witnessed the best and worst of Goldsboro.

“Shootings, drugs, prostitution,” Houston, pastor of Allen Chapel A.M.E Church, lamented.

But she also watched the community galvanize in ways she had not expected during last year’s protests. Allen Chapel became ground zero for protesters, civil rights groups and organizers. Local community leaders and prominent national activists met in her sanctuary.

“African-Americans who had been crying silently in their spirits for change,” she said, finally found a voice. “If you’re going to bring about change you can’t be timid, you can’t be fearful, you’ve got to kind of put yourself out there.”

On Father’s Day, Houston wore a flowing black robe embossed with two red crosses. During Sunday services, she asked the men and the boys in the congregation to stand.

“As we pray for the city of Sanford, as we pray for the lawyers and the judge and the jurors, we pray today for the family of Trayvon Martin.” Houston then stepped from the pulpit to a candle holder placed off to the side.