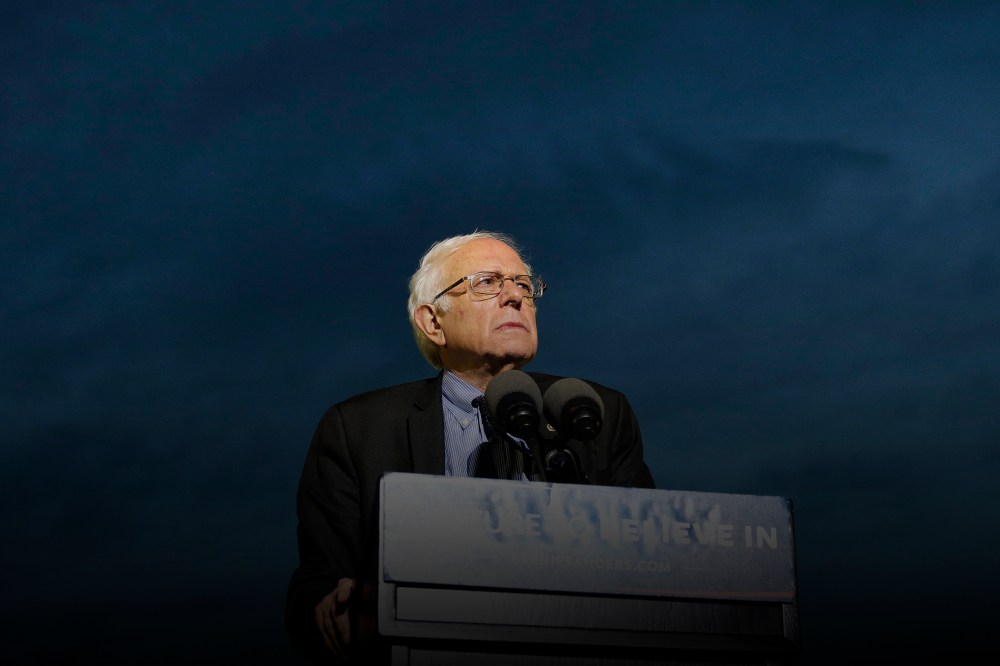

The contest may be over, but the mission is not for Bernie Sanders and his supporters.

Winning the Democratic presidential nomination is all but impossible given the current delegate count, so it’s on to Plan B: Sanders will spend the next 79 days before the Democratic National Convention accruing as much leverage as possible before he sits down at the bargaining table.

“The power of the political revolution to shape what comes out of the Democratic convention will be in proportion to the vitality and engagement of the people who have poured themselves into the Sanders campaign thus far. So it is critical not to let up or step back,” said Ben Wikler, the Washington director of MoveOn.org, which has endorsed Bernie Sanders. “Every door that a Sanders volunteer knocks on, every call that a supporter makes, every dollar raised online, every video shared, is a message to the Democratic Party that this is where the energy is.”

RELATED: Hillary Clinton’s five-step plan to beat Trump’s personal attacks

For that to work, Sanders needs to keep his base engaged and maintain at least a credible threat that he’ll make trouble for Democratic Party in November if they don’t play ball. Falling in line would meaning give up all negotiating power before negotiations even begin — and as Sanders often says, his campaign is about more than winning.

Campaign allies, while still suspending disbelief that they cannot find a path to victory, have not decided how to cash in their chips yet. They just know they want to accumulate as many chips as possible before they have to.

One camp wants to focus on policy, such as getting pieces of Sanders’ agenda enshrined in the Democratic Party platform. Another wants to focus on the process of picking the Democratic nominee — for instance by getting rid of super delegates or opening more primaries and caucuses to independent voters — arguing that the platform is worth little more than the paper it’s printed on.

Charles Chamberlain, the executive director of the pro-Sanders PAC Democracy for America, said the key question now is, “whether the Democratic establishment is going to bring our party together by embracing our fight for a political revolution or tell us to sit down, shut up and fall in line.”

Regardless of which camp dominates or how the party reacts, Sanders needs to remain a thorn in Clinton’s side if he hopes to get anything.

Clinton has expressed frustration at Sanders’ conditions for surrender, saying she never did the same for Obama in 2008.

But Clinton fought until the final vote was cast on June 4 and made statements that sound familiar to those made by Sanders’ supporters now. “I want the nearly 18 million Americans who voted for me to be respected, to be heard, and no longer to be invisible,” Clinton said on the final night of voting.

“I understand that a lot of people are asking, ‘What does Hillary want?’” Clinton continued eight years ago. “Well, I want what I have always fought for in this whole campaign,” she added, before enumerating a list of requests from universal health care to ending the Iraq War.

RELATED: Clinton and Sanders each say party unity is the others’ job

Clinton’s name was actually written into the section on women in the 2008 party platform.

Still, Clinton wasted little time after the final primary and quickly met privately with Obama at the home of Sen. Dianne Feinstein and endorsed her rival. But it’s not uncommon for candidates to want to influence the party after they lose.

For Sanders, unlike Clinton, falling short of victory was always the most likely outcome.

Running for president was largely a means for Sanders to push forward a “political revolution,” which he’s been trying to expand like an inkblot since 1980, when he was elected mayor of Burlington, Vermont, by a margin of 10 votes.

If he can’t take his revolution to the entire country, then Sanders has set his sights on bringing it to the Democratic Party.

“Our job is to revitalize American democracy,” he said in Oregon Thursday evening. “And the Democratic Party has to reach a fundamental conclusion: Are we on the side of working people, or big money interests?”