The incarceration of Japanese Americans from 1942 to 1946 remains a significant part of World War II history, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 notoriously eliminated the constitutional rights of people of Japanese ancestry while simultaneously portraying them as the foreign enemy.

The%20first%20thing%20I%20thought%20when%20I%20stepped%20off%20the%20train%20was%2C%20%22I%20don%27t%20belong%20here.%22′

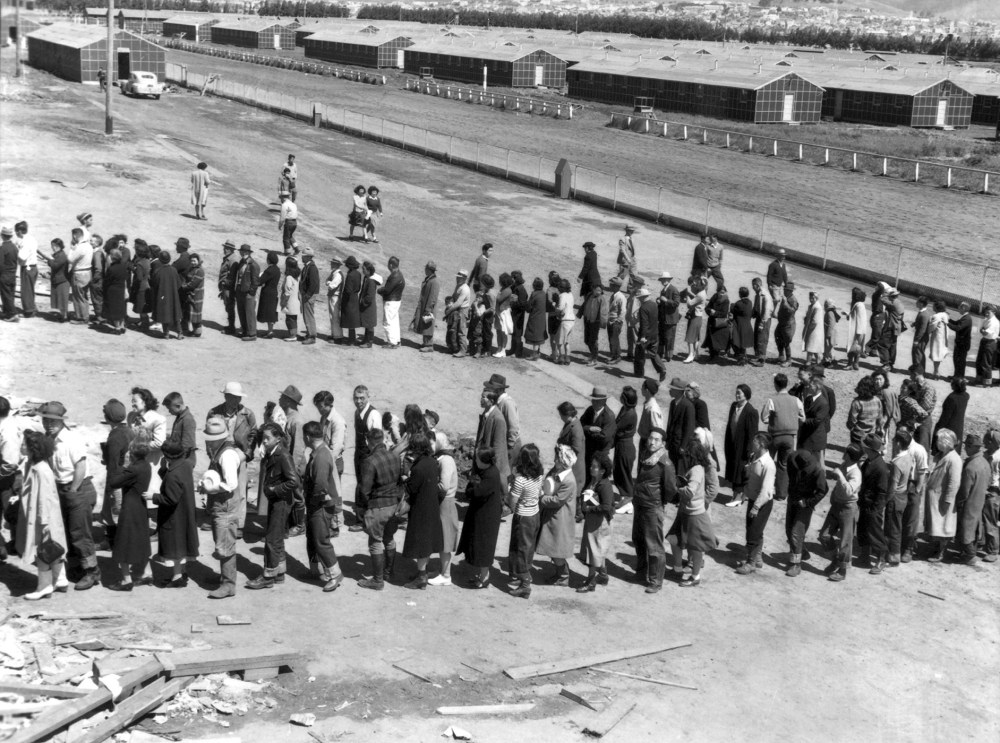

Approximately 120,000 Japanese, over two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens, were forced to leave their homes and move into a designated one of 10 camps that were established along the West Coast by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). The most controversial camp was the Tule Lake Relocation Center, which was later renamed the Tule Lake Segregation Center and turned into a maximum-security prison camp for those labeled as “disloyal” to the government because they did not answer “yes” on questionnaires asking if they would swear their allegiance to the U.S.

World War II lasted six years, ending in September of 1945. Tule Lake Segregation Center closed on March 20, 1946.

NBC Asian America spoke with five Americans who recounted the years of their lives spent behind the camp’s barbed wire, the ways in which their community fought back, and how, years later, they continue to find healing through collective memory.

Satsuki Ina (b.1944) was born in the Tule Lake Segregation Center to kibei (those who were born in America, but educated in Japan) parents, who were separated when Ina’s father was sent to Fort Lincoln internment camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, after answering “no-no” to the loyalty questionnaire. After her family’s release at the end of the war, Ina grew up in San Francisco, then went on to become a university professor and psychotherapist specializing in trauma. She’s also filmed two documentaries: “Children of the Camps,” which follows the journey toward healing for six Japanese Americans who spent their childhoods in the camps, and “From a Silk Cocoon,” a drama based on the letters, diary entries, and haikus Ina’s parents saved. “From a Silk Cocoon” won a Northern California Emmy Award in 2005.

I%20always%20thought%20that%20a%20tradition%20of%20being%20American%20is%20that%20you%20protest%20when%20you%20feel%20you%20are%20being%20treated%20unjustly%20and%20not%20according%20to%20the%20Constitution.%20We%20were%20only%20being%20American.’

Hiroshi Kashiwagi (b.1922) was born in Sacramento, California, and was 19 years old when his family went to Tule Lake. He refused to answer the infamous questions 27 and 28 on the loyalty questionnaire and was branded as a “no-no boy.” He renounced his U.S. citizenship soon after, and won it back in 1959. Kashiwagi attended UCLA while writing and performing plays with his theater group, the Nisei Experimental Group, and has appeared in several films. Kashiwagi is also a published author whose work includes “Swimming in the American,” his personal memoir that won the 2005 American Book Award. Kashiwagi is a lifetime member of the Dramatists Guild and the Screen Actors Guild.

George Nakano (b.1935) was six years old when his family was sent to the incarceration camp in Jerome, Arkansas, following Executive Order 9066. They were transferred to Tule Lake when Nakano’s parents remained undecided on the questionnaire. After college and a brief teaching career, Nakano became involved in local politics and was the first person of color to be elected city councilman in Torrance, California. After 14 years, he served as a California State Assemblyman. Some of his accomplishments in office include creating the first-ever Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs, and passing a resolution honoring State Senator John Shelley and Assemblyman Ralph Dills, the only two members of the California State Legislature who voted no on Executive Order 9066.

Jim Tanimoto (b.1923) was helping his family run their peach farm in Gridley, California, when he was ordered to relocate to Tule Lake. Tanimoto is the sole surviving member of Block 42, which was comprised of 36 Japanese Americans who became widely-known after they were jailed for refusing to fill out the loyalty questionnaire. Tanimoto moved back to Gridley after the war and today speaks about his experience at local high schools and colleges. He’s made the pilgrimage to all 10 war relocation camps.

Jimi Yamaichi (b.1922) grew up in San Jose during the Great Depression and was transferred with his family from the incarceration camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming, to Tule Lake, where he was hired as the construction foreman to build the camp’s concrete jail. He was one of 27 inmates in Tule Lake who resisted the military draft and, after a court hearing, had all charges dropped. After his release, he helped construct the Japanese American Museum of San Jose, where he continues to volunteer as a museum curator.

For the issei, or the first generation of Japanese immigrants to come to the U.S., farming became the biggest economic foundation, especially in California. With the continual influx of Japanese immigrants in the early 19th century and their successes in farming came white fear. Many discriminatory acts, such as the 1913 California Alien Land Law, were passed to prevent them from owning land.

Jim Tanimoto: It was hard growing up, as this was during Depression times. My father had a large family to feed, and it was nothing but work, work, work. We had what was known as the Alien Land Law, basically aimed at the Japanese immigrants. They couldn’t own land or business, so the way we got around it was that we registered our land in the name of our Hawaiian-born friend. We had two sets of books: one set for the government and the other for the family. It was our own peach farm, but it looked like we were working for our friend.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy executed a surprise military attack on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, killing over 2,000 and wounding another 1,200. Terrified and angry, Americans scapegoated those of Japanese descent, who already had a long history of being discriminated against as a minority group in the U.S.

Jim Tanimoto: It was a Sunday. We were out in our orchard pruning peach trees and we didn’t have a TV, so we were listening to the radio, and when we came back home for lunch, my father said, “Listen to this!” We heard that Japan was attacking the Hawaiian Islands. We didn’t believe it, it couldn’t be true. But the radio kept repeating the same thing, over and over.

The next day, we went into town. And all of a sudden, there was something there that you couldn’t touch, but you knew it was there. You were on one side, and they were on the other side. That’s when the discrimination actually started for us, the very next day. If you went to the grocery store, nobody would wait on you. On the street if you met somebody that you knew, they would ignore you, cross the street, or go inside. They wouldn’t talk to you on the street, because somebody would call them a “Jap lover.”

Jimi Yamaichi: There was this theater that all the kids went to, the California Theatre on South 1st Street that still stands today in San Jose. We could all go to the theater, but we weren’t allowed on the ground floor. We wanted the best seats and we told them we had the money to pay for them, but the people working would say, “We don’t want Japs there.” We had to sit way up in the balcony area, and everyone referred to it as “n****** heaven” because that’s where black people had to sit too, because of Jim Crow laws. It was so hot up there because that’s where the projector was, emitting all this heat. So we were sitting up there, sweating, and we could see that all the seats on the ground floor were empty. But we couldn’t sit in them.

The%20Constitution%20didn%27t%20mean%20anything%20for%20people%20of%20Japanese%20ancestry%20in%201942.’

We took only what we could carry, and of course we took more things than that. My mom made duffel bags out of a tent we had so we could carry our clothing. We had a flock of chickens and we didn’t want to leave them behind or give them away, so I had to butcher them all and my mother cooked them down so that we could put them in Mason jars and add them to the duffel bags with all the clothing. I could never forget the horrible act of chopping their heads off, one after the other, and the fluttering around. We took them to camp, and when the food was bad, and we felt hungry, we would open one at night. I still remember how good they were.

The Tule Lake Relocation Center was opened May 26, 1942, in Siskiyou County near the southern border of Oregon. The center originally held Japanese Americans from western Washington, Oregon, and Northern California.

Jim Tanimoto: The first thing I thought when I stepped off the train was, “I don’t belong here.” I had just graduated from high school, where we had covered the Constitution and learned what it stood for, and what it was supposed to do for American citizens. Everything was ignored. The whole Constitution was ignored. The Constitution didn’t mean anything for people of Japanese ancestry in 1942.

Hiroshi Kashiwagi: It was very strange because although we all came from the same area, we didn’t know each other too well. You were among strangers living very close together, sharing the mess hall food and the latrines. It took a while to get used to it. I worked in the hospital because they had running toilets. If you’re not being treated at the hospital, you go to the outhouses with everyone else. And though we were used to that in the country, there were all these people in there with you, which was very odd, and you had no privacy. So I got a job at the hospital where they had private, flushable toilets.

Jimi Yamaichi: We had to live with limited supplies. The one thing they did give us a lot of was rolls of toilet paper, which served many purposes. You had to take your roll to the latrines, of course, but also to the mess hall for your napkins, and you needed it for tissues, too. Even years after the war, a lot of us got used to carrying a roll of toilet paper around.

George Nakano: I remember the conditions at Tule Lake being harsh, especially in wintertime with all the snow we had to stomp through and the cold wind blowing through our barracks at night. The summers gave us better weather. Tule Lake had a small canal where the water was, and some kids wanted to go swimming, and I remember the MP [military police] that was up in the guard tower was pointing his rifle inward, commanding everyone to stay away from the water, because the canal was too close to the fence.

Hiroshi Kashiwagi: In my free time, I joined a club to write and also a little theater where we performed for the inmates, and we had an audience every night because we didn’t get movies imported into camp at the time. We performed American plays, pretending to be Caucasian. They were all short, one-act plays. It was great while it lasted, but it stopped with the loyalty questionnaire we got in February. We had a play in production that we never got to perform because the questionnaire put us in different categories, and some of us deferred, and so the camaraderie was gone. It became all very political. I was just enduring the days, and sitting out the years.

Jimi Yamaichi: I started off at the jail. I built the concrete jail. I was in charge of a construction crew of 250 guys. My crew laughed at me when I told them what we had to do and said, “What dumbass is going to build a jail for himself?” It took about six months to finish the jail. I was not very popular with the people in camp when the jail went up. “Yamaichi,” they would say, “this is pro-administration.” But it paid money, and $16 a month meant a lot to a lot of people.

As a way for the War Relocation Authority to determine the loyal from the disloyal, a required questionnaire was dispersed throughout all 10 camps to those over 18 years of age in 1943. Question 27 asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” Question 28 asked, “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?”

Those who answered “yes-yes” were released early or moved out of Tule Lake, and those who answered “no-no” or deferred were branded as disloyal, and were imprisoned at Tule Lake.

Jim Tanimoto: The camp was basically peaceful. Everyone was objecting to the fact that we were behind barbed wire, but we accepted it. But once the loyalty papers were passed out, it was different. Thirty-six of us in Block 42 refused to answer this questionnaire. If we didn’t answer it, we could be fined up to $10,000 and jailed for 10, 20 years. Even with this threat, we didn’t sign it.

Our whole block was surrounded with soldiers armed with rifles and bayonets a few days after we didn’t turn in the papers. As we finished our dinner at the mess hall and came out, we were sorted, separated, and I was taken with half of the men out of the camp to a building. It wasn’t until I saw the bars that I realized I was being put in jail. The administration was trying to make an example of us so that other blocks wouldn’t do the same thing. It turned out to rally everyone together — the other inmates saw us leave for jail and, in an effort to support us, they resisted the questionnaire too.

Satsuki Ina: My parents had a sense that America was not going to be a good place to raise their children, and they resolved that the only good place for their children’s future was in Japan. They both said they hoped Japan would win the war — not so much as a disloyal statement toward America, but more to ensure they would be on the list to go back to Japan. Once they said “no-no” to the questionnaire, our family was automatically branded as “enemy aliens,” and no longer American citizens. Many kibei were sent to Department of Justice camps, and my father was taken away. My mother was left alone with two very small children.

George Nakano: The conditions in Jerome were much better compared to Tule Lake. We were there for one year, and because both my parents did not answer a simple “yes-yes” on the loyalty questionnaire, we got sent to Tule Lake. What’s interesting is the question asked of my mother: “Would you be willing to serve in the WAC or the military nurse attachment?” She answered “no” because she had two children to take care of. At that time, my sister was four years old and I was seven years old. If she were to be gone, along with my father, who’s going to take care of the kids? Did they ask this question to every American female? No. They only asked those who were in camp.

Hiroshi Kashiwagi: The famous questions 27 and 28 were: “Would you serve in the armed forces?” and my response was, “Why should I? I’m being imprisoned.” The second one was: “Are you loyal to the United States, and would you withdraw your allegiance to other powers?” Ridiculous question, because obviously we were loyal. We had followed the order to leave our homes. We knew we had our rights guaranteed by the Constitution, and we had done nothing except that we looked like the enemy. We had a right to refuse, so I didn’t answer the questions, which put me in the “no-no” category.

Tule Lake became a segregation center on July 15, 1943, and 12,000 “no-nos” and their families were transferred there from other camps. Tule Lake became overcrowded and violent as the friction intensified between the “troublemakers” and those who complied with the administration. Inmates found other ways to protest their imprisonment.