INTRODUCTION

I was a young boy in Pakistan, my grandfather used to tell me stories in the moonlight before I fell asleep. Some nights he would read to me Iqbal or Rumi or another Persian poet, and some nights he would sketch out a parable, adapting a snippet of classical literature or a lesson from the Qur’an so that a child might understand. He was a wise and kind man, soft-spoken and thoughtful, who believed in two things above all else: education and the fundamental dignity of each person. Many of his stories, indeed most of them, were variations on those themes, lessons of integrity, mercy, and charity.

One sweltering summer night when I was eight or nine years old, he sat on the edge of my cot and paraphrased some Rumi: “So what if you are thirsty? Always be a river for everyone.”

That idea lingered with me. When I was grown and married and had children of my own, I often repeated those sentences to them. The translation from Persian to English is not technically precise, but the sentiment is unambiguous. Always try to comfort others, even if you are suffering. Offer compassion to your neighbor, to the stranger, to the roiling, boisterous masses of humanity. Share your gifts with the world, no matter how meager those gifts may be.

Those twelve words, I’ve learned in my sixty-seven years, are a good and useful guide to a life well lived.

I have known thirst, as we all have, though it has not defined my life by any means. I was raised by parents and grandparents who never had much but always enough, and who loved me deeply. I have been married to an angelic woman for forty-two years, and together we raised three happy, healthy boys who each grew up to prosper in his own way. Though I came from a poor family, I was able to be educated at some of the finest universities in the world. I became a successful attorney. Many of those blessings and many others were made possible because my wife, Ghazala, and I immigrated to the United States, and had the chance to avail ourselves of its boundless promises of equality and freedom.

Still, there have been times of thirst. I grew up in an autocratic society, where the freedoms I cherish in America did not exist. There were years, when I was much younger, when I had barely enough rupees in my pocket to feed myself, and there were nights when I had no proper place to lay my head. But in the long context of my life, those were minor inconveniences, momentary troubles.

Then there was this: In 2004, our middle son, Humayun, was killed. Humayun was a captain in the United States Army, and he was killed by a suicide bomber outside Baghdad. The Army posthumously awarded him a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart, and he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. Because he died early in the war, and because he was one of the first Muslim American soldiers to sacrifice his life in Iraq, reporters were interested in Humayun. I spoke to a few of them, mostly after his burial, and the stories they wrote were respectful and accurate.

Then the world moved on, as it should. Ghazala and our sons and I grieved in private, slowly rebuilding our shattered lives. In Rumi’s construction, we were desiccated by thirst. It was difficult to breathe at times, let alone be a river.

A dozen years passed. We remained, through all of them, private people, which is our nature. We were just another middle-class family in a small Virginia city, living our anonymous lives.

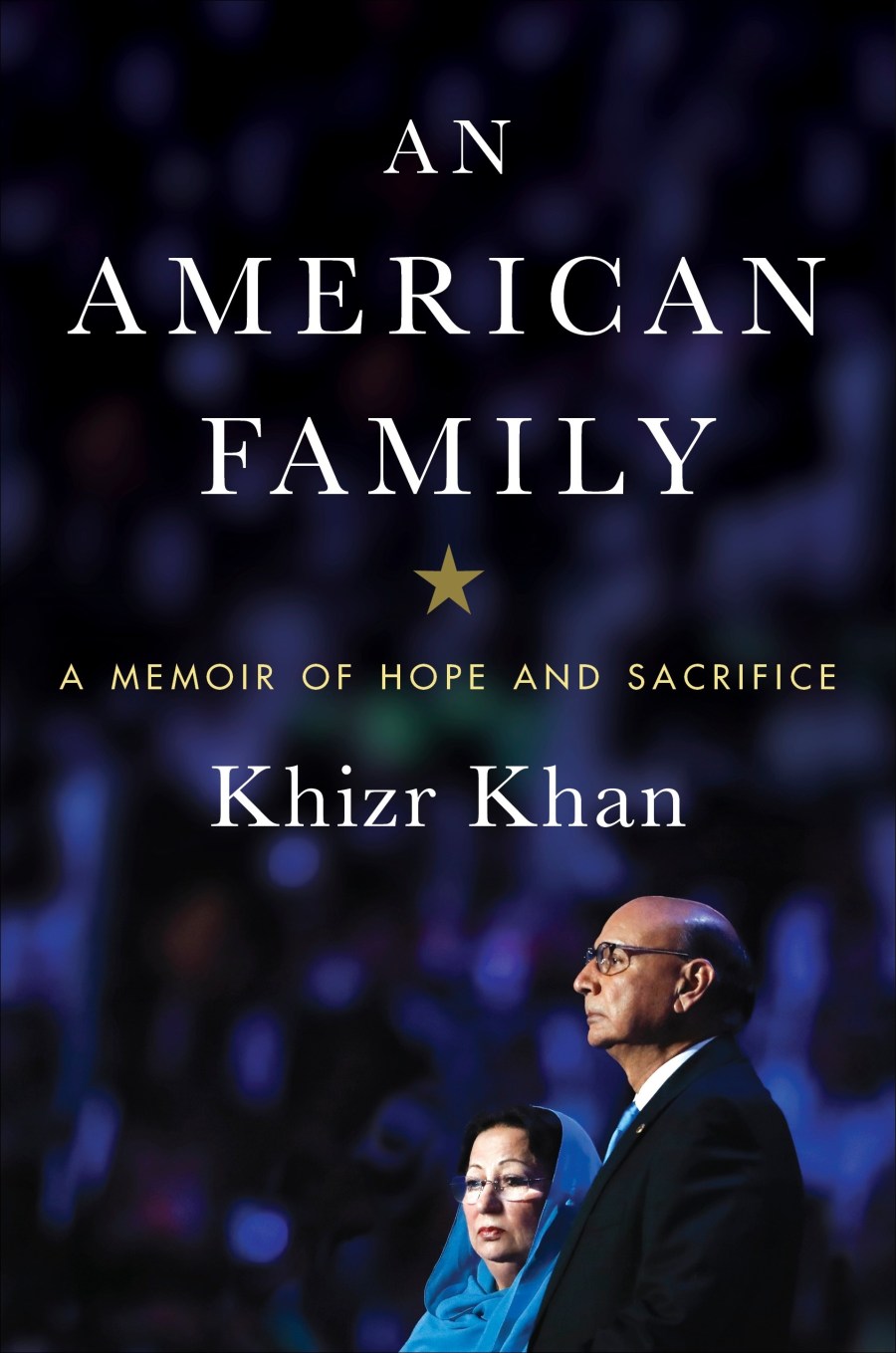

In the summer of 2016, however, we were invited to speak at the Democratic National Convention. We were hesitant, but Hillary Clinton, the candidate we favored, had planned a tribute to Humayun that night. She’d spoken eloquently—and apolitically—about his sacrifice in the past. It seemed only proper that we stand for him, too. So we took the podium, as I put it that night, “as patriotic American Muslims with undivided loyalty to our country.” Ghazala was too overcome with emotion to speak, but I addressed the Republican candidate, Donald Trump, directly. Over a period of many months, he had repeatedly called for Muslims to be banned from entering the country. I reminded him that if his position had been policy, our son never would have become an American. I reminded him, too, that he had disrespected women, judges, minorities, even the leadership of his own party—a mean and persistent sorting of people into those who would be welcome in Trump’s America and those who would not. His was a campaign fundamentally at odds with American values, with the founding principles of a great and inclusive nation.

“Let me ask you,” I said. “Have you even read the United States Constitution?” I held up a pocket-sized version. “I will gladly lend you my copy.”

I had carried that Constitution with me for years. It was dog-eared and creased, marked with notations and highlights. I had studied it, and I had long cherished the words, the ideas, embodied within. To celebrate it publicly, to hold it up as a reminder of what America is supposed to be, seemed the most patriotic thing I could do.