North Carolina’s Democratic governor, Bev Perdue, decided not to seek reelection at the start of 2012. From the moment she took office after a razor-thin 2008 victory, she has been embattled, duking it out with an uber-conservative state legislature over issues of education, reproductive rights, and voter suppression. Having been badly bruised by these battles, Gov. Perdue bowed out of the 2012 race.

She won’t be governor for much longer–but in these final days of her state leadership, Gov. Perdue has a chance to right an egregious wrong. I see she’s still weighing her final decision; that’s why I decided to send her a letter.

Dear Gov. Perdue,

It’s me, Melissa. I must admit I’m sorry to see you go.

I once described you as the “Thin Blue Line” because you have so fearlessly used the power of your office to stall, redirect, or halt the radical conservative agenda of Republicans in North Carolina. To protect the state’s environment, you vetoed a bill to authorize hydraulic fracking. To ensure fairness for workers, you vetoed a bill that would have increased health insurance costs for teachers. To shield vulnerable homeowners, you extended the state’s Emergency Foreclosure Program.

I know it has been hard. I know you often lost. But you did not shy away from fighting the difficult battles when issues of fairness and justice were on the line. Which is why, as you prepare to leave office next week, I am going to ask you to take up one last cause and to use the power of your office to do what only you can do.

Gov. Perdue, it is time to pardon the Wilmington Ten.

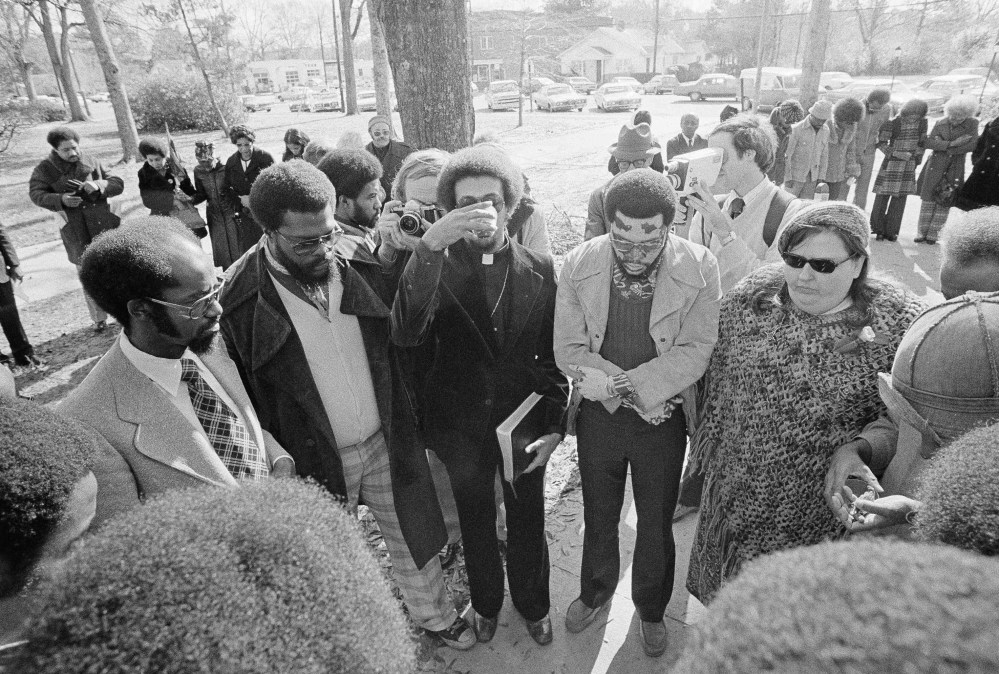

As you know, in 1972, nine young African-American men and one white woman were wrongly convicted of firebombing a Wilmington grocery store during civil rights protests. Most of the Wilmington Ten were just teenagers at the time. But despite shaky evidence, the young musicians, students and activists were sentenced to a total of 282 years in prison.

Gov. Perdue you once stated that “there’s nobody in America…who could say that trial was fair or that there wasn’t some kind of undercurrent or overt racism involved in the jury selection.”

Indeed, it was so overt that by 1977, at least three witnesses had recanted their testimony. And in 1980, the U.S. Court of Appeals overturned the convictions of the Wilmington Ten–noting that the chief witness lied on the stand and that prosecutors concealed evidence.