For years, I have defended Greek life. I have proudly worn my sorority’s arrow necklace since my junior year of college. Both in public and in private, I have told the naysayers about my positive experience and pushed back on the negative stereotypes levied against me and my fellow Greeks.

But I can’t, in good faith, do that anymore. The way the system is now, the costs far outweigh the rewards.

How can any of us when fraternity men are 300% more likely to rape than non-fraternity men? When sorority women are 74% more likely to be sexually assaulted than other college women?

The deep-rooted problems of sexual assault at the University of Virginia are not isolated. And while it is, in some sense, inherently an institutional-level question — How are schools adjudicating cases of students who choose to press charges? — it’s also a question about the Greek community at large — How long can we keep quiet about the darkness associated with Greek organizations, even when they are not our own?

The brothers of Phi Kappa Psi are front and center in the Rolling Stone story for the alleged perpetuation of an environment where raping, assaulting and treating women as substantially less than human is not only allowed, but encouraged. Also remarkable was the tacit allowance of this behavior from Jackie’s — the victim’s — friends when she told them of her alleged rape and they responded, not just with doubt about her story, but with concerns for their own social standing.

According to Rolling Stone, her friends said, “‘Is that such a good idea?’ [Jackie] recalls Cindy asking. ‘Her reputation will be shot for the next four years.’ Andy seconded the opinion, adding that since he and Randall both planned to rush fraternities, they ought to think this through.”

Sexual assault was no foreign concept on campus when I was in college — and unfortunately, I don’t think that’s changed in the two years since I’ve graduated. The first few weeks of my freshman year were full of fraternity-sponsored parties, each seeking to attract the “hottest” freshmen girls in order to attract a “cooler” set of future male pledges. He who partied with (and hooked up with) the best-looking girls could claim top-tier frat status. And if freshmen boys also happened to get laid at these pre-rush parties, all the better.

Those fond memories would translate into wanting to pledge that house, with those brothers who were his wing-men. One day that guy would make that same assist for the next generation of brothers. And so on.

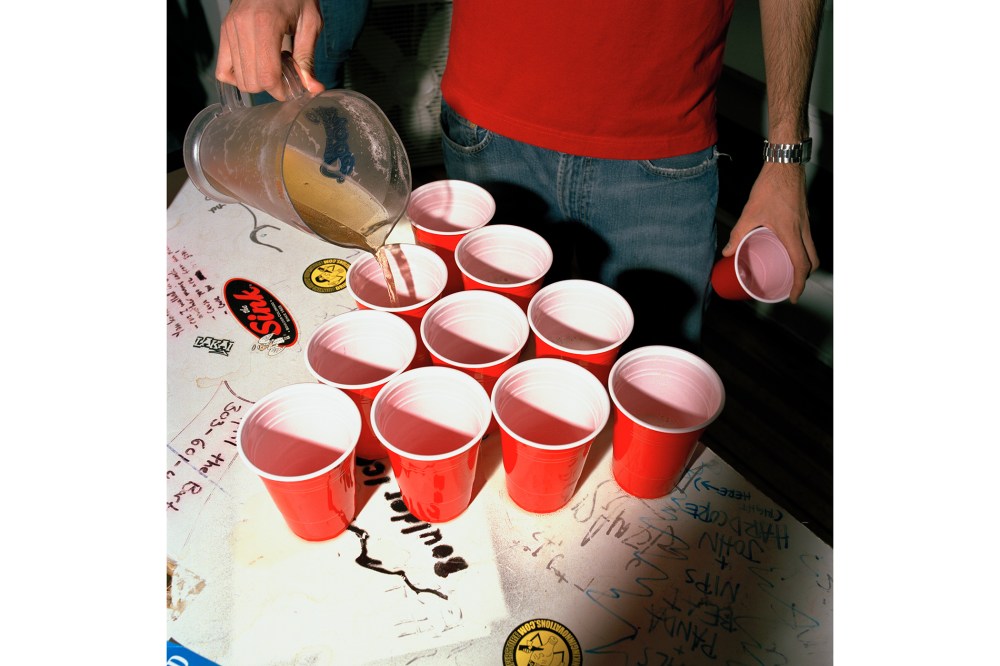

Girls were wooed, promised free booze, invited to exclusive parties, and pushed to drink more, have fun, “be chill.” If I drank from the vat, I’d be cool. We all drank from the vat without questioning its contents. Sexual assault and date rape always loomed, though usually laughed off nervously or couched in typical teen thoughts of invincibility and “that won’t be me.”

We all knew which houses were infamous and why. At that time, one fraternity house had risen to somewhat-national notoriety for a hazing incident that involved crab-boiling their pledges. They lost their charter and were kicked off campus. They were technically gone, but not really, and they maintained their reputation on campus as the “date rape frat.” But even with that reputation, freshmen flocked to their parties.