Before author and rhetoric professor Nancy Reddy had her first child, she imagined that motherhood was instinctive and natural — sparked by an overwhelming, instant love that would make caregiving easy.

Then she actually became a mother. “I hadn’t been made milder, willing to give up sleep, ambition, the time to finish writing a sentence because I loved the baby so much,” she recalled. “I was a bleeding, leaking mammal, weeping in the produce section and fighting with my husband in the parking lot of Costco, but quietly so as not to wake the baby who had finally, finally fallen asleep in the back seat. I was a mother, and I was a beast.”

In those early days, Reddy struggled to live up to her idea of a “good” mother. Then she had a revelation: “Goodness was the trap.”

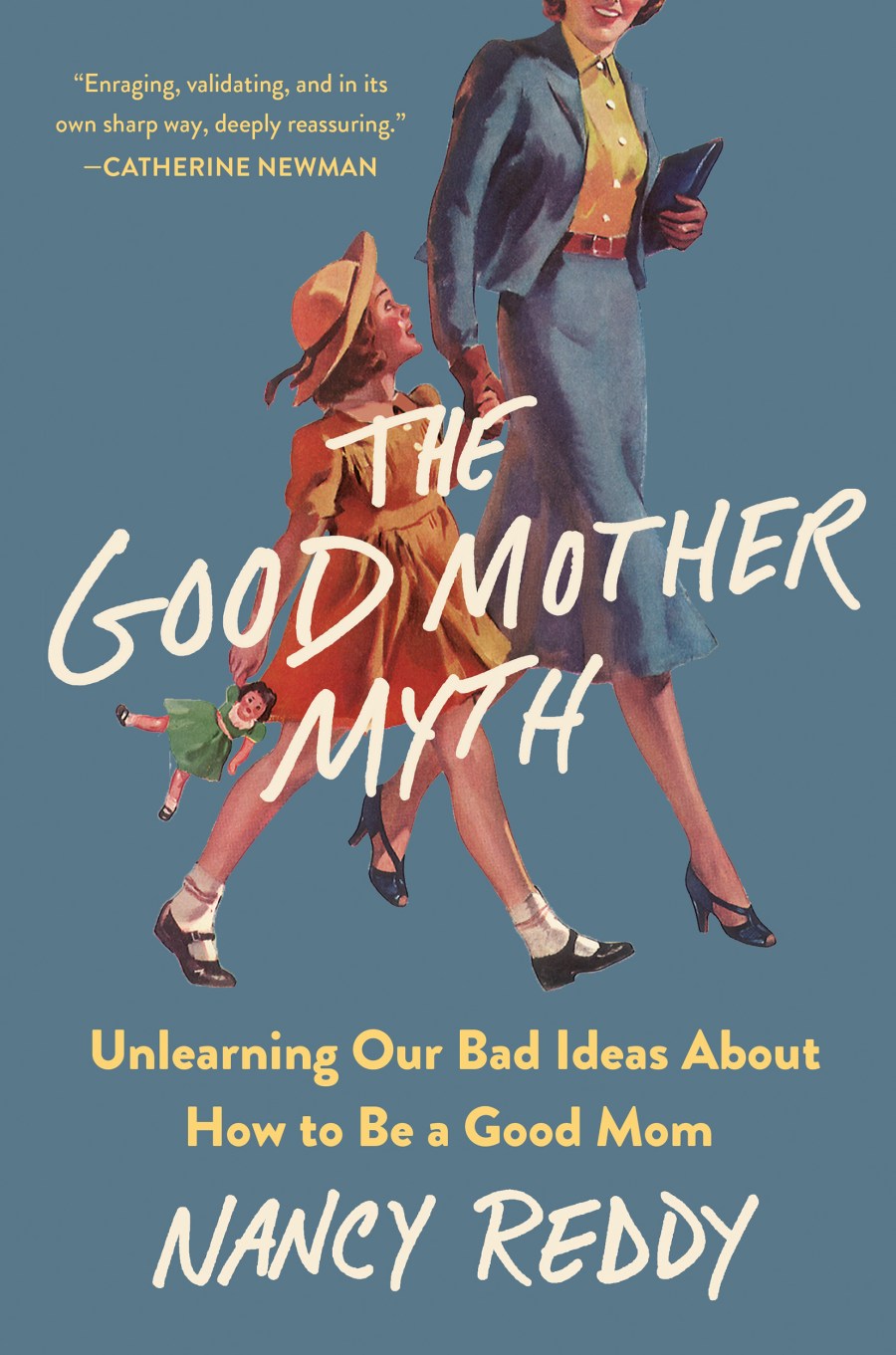

That concept became the basis for her new book, “The Good Mother Myth: Unlearning Our Bad Ideas About How to Be a Good Mom.”

Part memoir, part cultural criticism, Reddy pulls back the curtain on the flawed social science behind our current thinking of what makes a “good” mother.

Having been raised by a single working mom, Reddy considered herself a feminist — barreling toward a Ph.D. while pregnant at the time. But as a new parent, she couldn’t understand why doing motherhood “right” felt so wrong.

In her search for answers, she turned to the research of mid-century social scientists and psychologists whose outdated ideas about so-called “good” motherhood have set the cultural standard for decades.

What Reddy uncovered was flawed lab studies, sloppy research, and straightforward misogyny from researchers like Harry Harlow, who claimed to have discovered love by observing monkeys in his lab, to the household name Dr. Spock, whose bestselling parenting guide suggests mothers instinctively have all the knowledge they need to raise children.

Reddy, instead offers a refreshing perspective of the wives who helped launch the careers of these social scientists, and focuses on the value of building community in early parenthood.

She recently shared what she’s learned from her motherhood journey as well as lessons from the book about how mothers can be better supported. Below is the conversation, which has been edited for brevity and clarity:

Know Your Value: When you first became a parent, what was your experience confronting expectations about motherhood?

Reddy: Before my first son was born, I had a really clear image of what I’d be like as a mother. I pictured myself sitting at my desk, my baby cradled against my body in a soft fabric wrap, caring for him while I wrote. He’d be totally content, and I’d be able to go on with my life just as I had before becoming a mother. (Can you tell I’d spent almost no time with actual babies?)

Needless to say, this is not how things went. My first kid was a tricky baby, and he spent a lot more time screaming than napping. I was so exhausted I could barely think straight from one end of a sentence to the other, much less zip away at my dissertation. When I wasn’t able to live up to that impossible ideal I’d conjured for myself, I felt like a failure.

I think a lot of new mothers come into parenthood with a similarly impossible and contradictory set of ideals. We expect that maternal instincts will kick in and we’ll just know what to do. We believe that the overwhelming love we feel for our baby will mean not minding the sleep deprivation or other hardships of the newborn period. And for a lot of women, we expect that being a good mom means doing it basically all on our own, powered by selfless maternal love.

It’s the aim of my book to uncover the origins of that mythology around motherhood and point the way toward a kinder, gentler way of thinking about raising kids that doesn’t depend on the unfailing labor of one perfect mom.

Know Your Value: Where does the myth of the perfect mother come from in American culture?

Reddy: We’ve got a long history of ideals around motherhood — it certainly goes back to the Revolutionary period and the idea that the (white) mother was charged with educating her children to produce good future (male) citizens — but the image of the perfect mother that plagues us now is most closely linked to the post-war/Baby Boom era.

That era right after World War II had the potential to be revolutionary for American culture, and in Europe it was, with a huge expansion of the social safety net. In America, millions of women had worked during the war, and state-supported daycares were created to support mothers of young children working for the war effort.

But when men started returning home from war, there was a lot of anxiety about getting them back to work, along with anxiety about what would happen to relationships between the sexes with women in the workforce.

So there was a huge amount of cultural pressure for women to become devoted wives and mothers, and the science of the day supported the idea that what a baby needed most was the total, uninterrupted attention of a primary caregiver. That’s how we end up with this ideal of the mother who wants nothing more than to stay home and care for her child — who’s doing “the most important job in the world,” but doing it basically alone.

Know Your Value: Why did you decide to write this book — what was missing from the discourse?

Reddy: When I started working on this book, we were in a boom of motherhood memoirs, and I found a lot of comfort in reading others’ stories about early motherhood. Seeing that other women had struggled as I had helped me feel less alone.

But those books didn’t fully answer my questions. If motherhood was, as I’d always been told, “the most natural thing in the world,” why had those first years been so incredibly hard? I’m a researcher by training and temperament, and I spent years really diving into research. I read about the history of birth, parenting across the animal kingdom, the neurobiological and cultural roots of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders.

In the end, the book is an investigation of the history of our bad ideas about mothering. We’ve got a whole mythology around mothers and motherhood in America, but we do so little to support actual mothers and families!

My book looks to the post-war science and social science that’s underneath our present-day ideas about how to be a “good mom.”

Even if you’ve never heard of Harry Harlow or John Bowlby or Mary Ainsworth, their ideas are still shaping our culture and policy today.

Know Your Value: What does your research teach us about the role of fathers?