Staring at an iPhone screen, I watched my father earlier this month attempt to focus his camera on our family’s newly-lit Christmas tree. The luminous and twinkling lights previously tangible to me in holidays’ past, blurred through FaceTime and a weak WiFi connection.

“It’s smaller this year, but I think it still looks nice,” he noted in his steady voice.

I squinted at the stout tree through the cracks on my iPhone screen, trying to re-immerse myself in the feeling of being home during the holiday season. Like many families across the U.S., the recent surge in coronavirus cases in the northeast made going home for Thanksgiving unfeasible, and now, Christmas too.

Decorating the tree with my dad and brother was a yearly ritual, which, up until this year, was largely unbroken. We’d giddily strap a Fraser fir tree to the roof of our car and drive 15 miles an hour to deliver the precious prize to our living room. We’d dust off boxes of ornaments — some dating back to my dad’s childhood — and gingerly hang them throughout the afternoon.

It was there in our New Jersey living room, tending to the Christmas tree, that we’d embark on the holiday season together. While Thanksgiving was always the boisterous gathering with extended family, Christmas was the quieter, intimate time with our nuclear family that kept the rest of the world at bay.

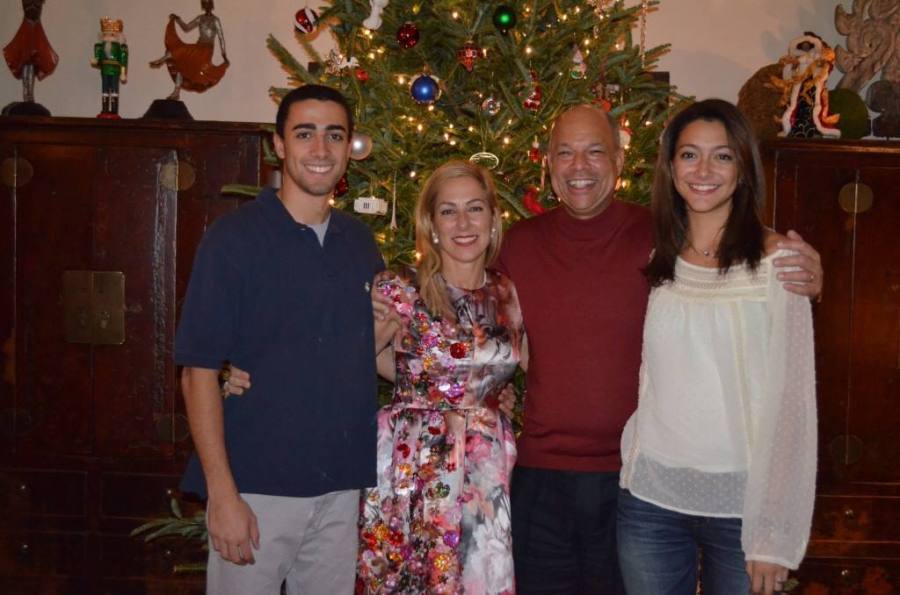

Even during the years my dad, Jeh Johnson, served as the secretary of Homeland Security, we managed to keep our Christmas traditions alive, leaving stress, work and politics at the door. Every year, no matter what events unfolded beyond our living room, we’d remark on what had remained the same through the years: family.

But this year has unequivocally changed us. Like so many other families, 2020 has shattered the luxury, or perhaps the illusion, of keeping the outside from filtering in. Seismic changes in the country unfolded before us this year: a pandemic that has taken over 300,000 lives, a job market on par to that of the Great Depression, and acts of police brutality, which sent shockwaves through the country, sparking a national reckoning on racial injustice from the movement for Black lives.

For us, we lost an indispensable family member in February, my Aunt Marguerite, who was my dad’s younger sister. Her sudden death at only 60 years old was untenable for all of us, especially for my dad. During all of the colossal changes this year, this holiday season also marks the first Christmas without her.

Watching my dad present his iPhone Christmas tree made me conscious of another change brought on by Marguerite’s death: my relationship with him had evolved. I began to stop looking at him in the parental-sense, as a caretaker for my wellbeing. In its place, I began to worry about him, and about his wellbeing. He became another adult in my eyes, with his own anxieties, fears, and pain to sort through.

But most of all, losing her caused a pain that is still as raw as the day we said goodbye. Her presence had always been a constant, providing an unspoken comfort just knowing she was just within arms reach. If she could be ripped from my life, I panicked, what else could happen this year?

I know I’m not alone. Dr. Dana Udall, a psychologist and chief clinical officer at Ginger, an online mental healthcare platform, told me that this year’s unpredictability is increasing anxiety for many.

One way people are understandably (but ineffectively) trying to grapple with the lack of control over this year is by overworking, Udall explained. “Sometimes people focus so much on their job because they might feel ‘I have a sense of control or efficacy at work,” she noted.

Rather than overworking which can backfire with additional stress, Udall offered a different advice: create a sense of routine. “Whether that is every morning going on a walk or doing a mindfulness or meditation practice, having a socially distanced social time with friends can be really important,” she advised.

“Focusing on things that we have a little bit more control over, and then part of coping is also being able to manage those tough feelings of anxiety. Finding ways to slow down and really process through anxiety can be incredibly important.”

In times that bring immense changes, reorienting your own relationship to change, can also be helpful, according to Dr. Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, a professor of English and Human Dimensions of Organizations, and director of the comparative literature program at the University of Texas at Austin.

“You can’t change facts, but you can change your relationship to them,” Richmond-Garza explained. As a result, people can often feel empowered by virtue of “being able to reorient yourself towards something.”