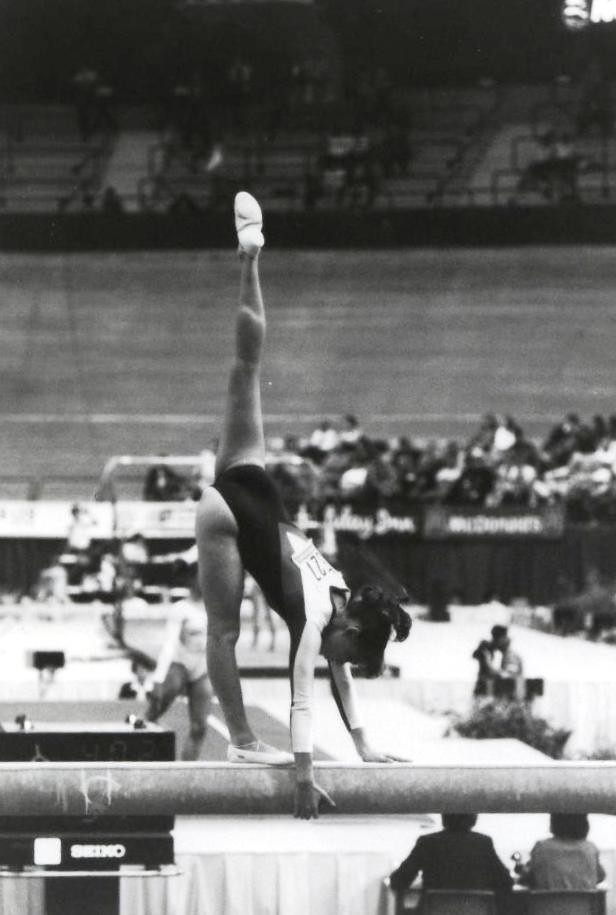

When Jen Sey was a child growing up in New Jersey, she never dreamed of becoming a business executive. Her life revolved around gymnastics. She started competing at the age of 5 and was training up to 50 hours a week. Sey went on to spend eight years on the U.S. national team and was named the U.S. women’s all-around national gymnastics champion in 1986.

But behind her incredible accomplishments was a life that was often filled with torment and self-doubt.

At the time, emotional and physical abuse were the norm in gymnastics, and cruelty was the accepted method of coaching, according to Sey, 52. The experience led her to write her 2008 memoir, “Chalked Up,” which details how despite her success, she never felt good enough.

Sey eventually left gymnastics behind and graduated from Stanford University with a degree in political science in 1992. She later took a job in advertising and climbed the ranks to become the executive vice president and global brand president of Levi’s. Looking back, Sey – who lives in San Francisco with her husband and four children – said her experience in competitive gymnastics helped find her voice and shape her leadership style today.

“I’ve learned that your life and journey is not a straight line, and you will get knocked down,” she told Know Your Value founder Mika Brzezinski. “When you advocate for yourself, it’s not always going to go the way that you want. But you keep going. There’s not another option.”

Sey chatted with Brzezinski about her past and the skills she transferred to her professional life today, success after the age of 50, her role in bringing greater diversity to her company and more.

Below is their conversation, which has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Mika Brzezinski: I want to talk about your past and how it relates to your current career. I’m wondering, as a gymnast, did you have skills that you’ve transferred into your professional life today? Are there any habits, skills, philosophies that you had to break away from?

Jen Sey: Very much so. … I spent my childhood amongst just terrible, cruel and awful coaches. And I learned the damage that can be done, not just to children, but I think to anyone.

…[From that experience, I learned that] I want to be a positive coach and leader. I want to create a positive environment. I think people do their best work in a positive environment … I never yell. I’m direct, I try to be helpful. I want to create the conditions for people to do their very best work and feel that they’re doing something meaningful. I want them to feel good about themselves. I want them to develop into not just better professionals, but stronger people.

… There were years and years of cruelty [while I was a gymnast] — and it was the cruelest at my most successful. I was incredibly stoic during that time that I was unraveling on the inside. And when I did finally walk away, I did unravel, and I continued to unravel for probably about 10 years. When you are just faced with abuse and cruelty every day, if you’re told you’re garbage, you believe you’re garbage. And so that has an impact on you.

I struggled, which is what led me to write the book [“Chalked Up”] 20 years later. I think writing the book allowed me to put myself back together in a way, and it was this sort of trigger point for me that I also just started to bring my whole self to work. Everybody knew my life story [after the memoir came out]. And you get better when you integrate all the parts of yourself.

I’m old enough to remember when women didn’t talk about their personal lives at work, and they didn’t have pictures of their kids on their desk and they didn’t want anyone to believe that they had a life outside of work. And then I wrote this book and I tried to keep it a secret, but then I was on “Good Morning America.” So, it wasn’t a secret anymore. And so, I just said, “OK, this is me, this is who I am.”

… The one thing I would say is positive about gymnastics. or sports in general … is this notion of a growth mindset … The idea that just because you can’t do something right away, doesn’t mean you’re not going to get it. And I am really, really disciplined about figuring stuff out and learning how to do stuff. [For example,] if I’d given up the first time I tried a back flip or any skill, then I never would’ve learned anything.

Brzezinski: At Know Your Value, we teach women to communicate effectively and be successful in whatever it is that they’re doing. And I notice a lot of women, when they come to me, they have a hard time with ambiguity. They have a hard time with change. They have a hard time with the unexpected, while men almost revel in all of that.

Sey: I think men, and I don’t want to totally generalize, but they are risk-takers a little more often. The unknown is not something that troubles me, and I’ve always been quite comfortable in ambiguity.

I think one of the things I’ve really had to do is almost rebuild myself … I suffered from imposter syndrome probably up until about last year. I didn’t even know it was a thing until 10 years ago. I went to Stanford coming out of gymnastics. I was convinced that at any moment, somebody was going to pop out from behind the curtain and tell me I didn’t belong. A lot of women, high achieving women in particular, have this.