On Monday, 24-year-old Gus Deeds was discharged from a rural Virginia hospital after a mental health evaluation, reportedly because there were no psychiatric beds available in the area, according to local media outlets.

The consequences seem to have been been exceptionally tragic: the day after being released, police believe, Gus Deeds likely stabbed his father, state Sen. Creigh Deeds, before killing himself. It’s not clear whether Deeds was ever diagnosed with a mental illness. But his discharge from Bath County Community Hospital appears to have been all too common: Americans are routinely shut out of mental health facilities across the country for lack of beds.

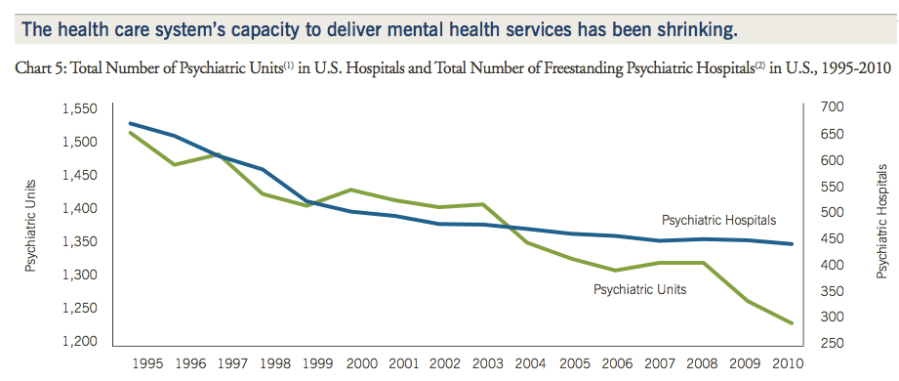

Nationally, the number of psychiatric beds has been steadily declining as hospitals moved away from institutionalizing patients and budget cuts have taken hold. The number of hospital beds in freestanding psychiatric hospitals has dropped 13% between 2002 and 2011, according to the American Hospital Association.

But the need hasn’t declined as quickly, and there haven’t been adequate alternatives to pick up the slack. Between April 2010 and March 2011, about 200 Virginia residents were deemed to be “in imminent danger to themselves or others as a result of mental illness or is so seriously mentally ill to care for self and is incapable or unwilling to volunteer for treatment.” But they were nevertheless released from custody because mental facilities didn’t have the capacity to admit them, according to a 2011 report from Virginia’s Inspector General.

In many major US cities, bed shortages have prompted emergency rooms to “warehouse” the mentally ill in holding rooms and hallways, where they languish without treatment. One Seattle woman who tried unsuccessfully to commit her mentally disturbed son in 2011 was told there were no beds available; he killed himself days later.

Civil commitment laws prohibit states from indefinitely detaining people who are deemed to require a mental health evalution or hospitalization. The 2007 Virginia Tech shooting prompted an overhaul of the process, but the basics have remained the same: once someone receives an official mental health evaluation in Virginia, that person can be taken into custody against their will for four hours with the approval of a local magistrate judge, as reportedly happened with Gus Deeds. But even if a mental health professional decides that person needs to be committed, if there is no bed available within four hours’ time—or six hours with a magistrate’s approval—he or she must be released.

“This is a problem for many states with large rural areas that have downsized state hospitals,” says Richard Bonnie, a University of Virginia professor of law and medicine. A new UVA study showed that beds could not be found in time for 4 percent of mentally ill people recommended for involuntary commitment in Virginia before they had to be released.

Part of the downsizing is by design: For decades, American psychiatry has been moving away from the state psych wards of old and toward more community-based, privatized, and outpatient care. But advocates say far too little has been provided to fill in the gap. More than 50% of US counties “have no practicing psychiatrists, psychologists or social workers,” the AHA reports, and just 27% of community hospitals have an organized, in-patient psychiatric unit. In rural areas, access is even more challenging, as patients often have to travel long distances to reach providers and hospitals, and crisis intervention services have been particularly lacking on the local level.

“People should not be locked up in state hospitals forever. The problem is that the community services which were supposed to be developed so that people could be served in the community aren’t being retained. That’s made access very, very difficult if someone really does need it,” says Mira Signer, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Virginia.