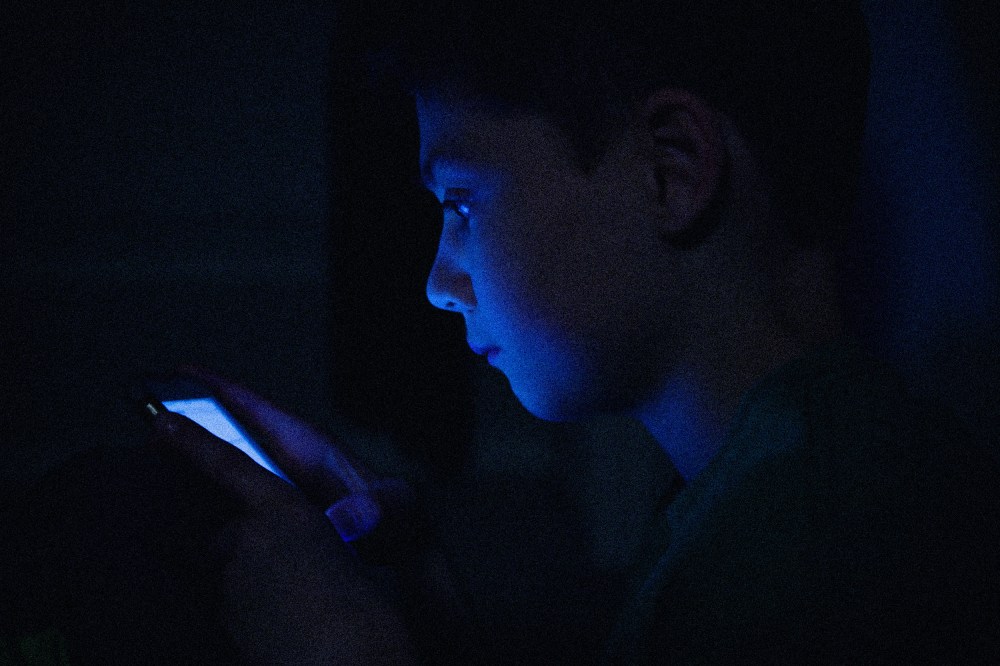

Facebook has once again found itself in hot water with Congress, with a hearing that kicked off Thursday after The Wall Street Journal revealed a number of internal problems at the social media company, including that it “knows Instagram is toxic for many teen girls.”

If Facebook has internal research that shows that parts of its services are detrimental to young users, the company should act on that research, not attempt to bury it.

Pressure is mounting on social media companies like Facebook and YouTube, as policymakers from both sides of the aisle call for greater regulation of harmful speech online. During Thursday’s hearing, Sen. Marsha Blackburn, R-Tenn., told the platform, “You’ve lost the trust, and we do not trust you with influencing our children.”

On the heels of the Journal report, Facebook’s chief technology officer, Mike Schroepfer, has resigned and Facebook announced a pause on its yet-to-be-launched Instagram Kids product. Facebook’s Oversight Board, the quasi-judicial body set to rule on the company’s big content moderation decisions, announced that it, too, would be investigating whether Facebook had been “fully forthcoming” to its own board.

A whistleblower appeared on CBS’ “60 Minutes” to expose secrets from her time on a Facebook research team. A whistleblower (it’s not been confirmed whether it is the same one) will also testify next week at one of the Senate hearings on online child safety.

This isn’t the first time Facebook has been in the spotlight, nor is it the first time the company has been dragged before Congress to testify on its practices. And it probably won’t be the last. Which raises a question from some: Is this the possible end of Facebook?

Personally, I don’t think it is. But I do think it’s worth thinking about what a post-Facebook internet might look like, and what it would take to get there. Because if we unexpectedly do see Facebook fail, it would irrevocably change the internet as we know it.

Right now, internet companies like Facebook have relative freedom in choosing how to host and moderate content on their platforms, thanks to Section 230 and the First Amendment. This has benefited the internet greatly, mostly by giving people the ability to communicate freely and connect with each other online. This freedom has also come at a cost, though, in the many harms of the internet — including the potential harm for teens on social media.

While delaying the launch of Instagram Kids is an obviously smart move right now, the company needs to do more to prove itself to be a trustworthy, responsible actor. If Facebook has internal research that shows that parts of its services are detrimental to young users, the company should act on that research, not attempt to bury it.

But Facebook doesn’t just need to fix its products. It needs to fix its relationship with America and the world. If Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan’s newly reinvigorated commission brings Facebook to court again, the company needs to — for once — actually follow through with whatever judgment is made.

Laws that restrict Facebook will likely also restrict sites like Wikipedia, Reddit, Etsy and many other smaller and newer platforms.

And what it needs to fix isn’t so much the specific details of its products — though strong efforts on that front are necessary, too. Facebook cannot launch any child-oriented product until it regains the trust of the American public. And that will take a lot more effort, including better technical safeguards across its products, better commitments to data privacy and online safety, and better public relations. It will take investing into civil society, not just through funding but through actual cooperation with researchers and advocates. It may even take an overhaul of Facebook’s core business strategy, which is based on data tracking and personalized advertisements.

If Facebook and its peers don’t step up, we’ll either end up with an internet that becomes more and more dangerous to its users or an internet that is so tightly regulated that we lose all the good parts of the online experience. (Think, for example, of laws like China’s recent rule restricting children to three hours of online video games a week.)