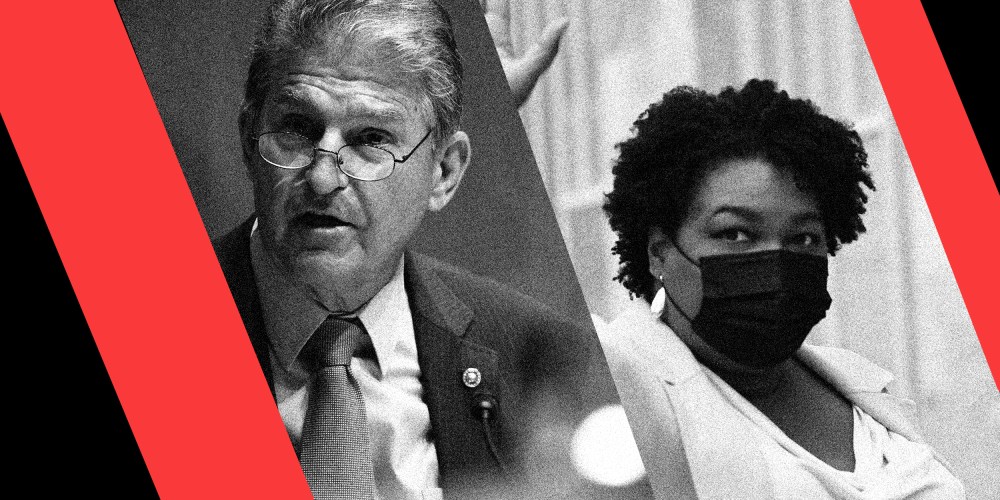

The For the People Act, the Democrats’ very popular voting rights bill, is dead in the water in the Senate. The Democratic caucus’ most conservative member, Joe Manchin of West Virginia, has made it clear that he won’t support any elections overhaul that isn’t bipartisan. After weeks of silence, Manchin has begun circulating a compromise proposal to his fellow senators.

So far, Democrats are receiving Manchin’s pitch well and slowly getting behind it as the only available option to stop Republicans in their crusade to suppress the vote. Even voting rights activist Stacey Abrams, who had advocated for a much stronger version of the bill without the voter ID requirements that Manchin is pitching, said she would endorse the compromise if it meant Democrats could do something instead of nothing.

Basically, Manchin is holding the reins on the issue — in a 50-50 split Senate, the entire Democratic Party has become beholden to him and his red lines. So it was very bizarre and unsubtle Thursday when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and his Republican colleagues decided to start referring to Manchin’s proposal as the “Stacey Abrams substitute.”

Why, one might ask, would Manchin’s compromise be renamed for someone who didn’t propose it, had nothing to do with crafting it and isn’t even a member of Congress? Because, frankly, many Republicans believe Black Americans’ participation in politics is inherently illegitimate. And this latest dog whistle is more of an air horn: Abrams, a Black woman who grew up poor in Mississippi and went on to mount a nearly successful run for governor in Georgia when it was still solidly a red state, represents everything the GOP is fighting to stop. Her face is inherently scarier and more distasteful to their base than the real face of the compromise — a 73-year-old white man who worships at the altar of bipartisanship.

Why, one might ask, would Manchin’s compromise be renamed for someone who didn’t propose it, had nothing to do with crafting it and isn’t even a member of Congress?

To be clear, this has nothing to do with actual political leanings. Abrams isn’t much more liberal than Manchin, nor has she dismissed bipartisanship as impossible. She isn’t politically aligned with the progressive wing that Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., or Reps. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., represent. In fact, she took heat from progressives when she campaigned to be President Joe Biden’s running mate and supported billionaire Michael Bloomberg’s run for president last year. She would never have made it in politics in Georgia, where she was minority leader of the state House of Representatives from 2011 to 2017, had she not been willing to reach across the aisle and work with Republicans. She campaigned for governor on that very skill.

But Georgia flipped blue in the elections because of record turnout and sent a Black preacher to the Senate, unseating a white male incumbent. The state’s reversal is emblematic of what Republicans fear about the future of politics and their party: When Black people —and especially Black women — turn out to vote, Democrats win. And though Abrams very narrowly lost her gubernatorial election in 2018, she has been instrumental in turning out the Black vote in Georgia.

I went down to Atlanta just before that election to report on the coalition of 300 domestic workers — almost entirely women of color — canvassing for Abrams. The largest independently funded ground game in the state was run all by women who spent their days cleaning houses or caring for other people’s children and then somehow found the energy and motivation to knock on doors for Abrams at night. Many of them had never participated in politics before, but they were inspired to see a woman on the gubernatorial ticket who looked like them and cared about and represented their interests.