When conservatives on the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, the justices effectively created a challenge to Congress to fix the historic law. To that end, voting rights proponents have crafted a solution, named after a civil rights hero and pioneer: the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

The Democratic-led House is scheduled to pass the bill (H.R. 4) in the fall, and in the Senate, the legislation has picked up a Republican co-sponsor — Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski — giving the proposal the kind of bipartisan support it’ll need to advance.

It was against this backdrop that Congress’ most powerful Republican this week took steps to kill the bill.

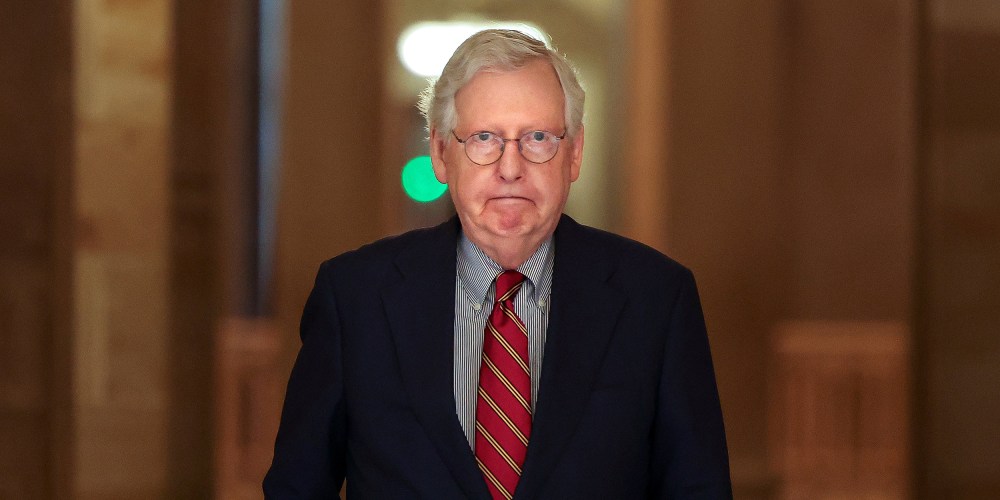

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell threw cold water on a bipartisan proposal to revitalize the Voting Rights Act, dooming any hope of Congress taking action on voting rights this summer. McConnell formally came out against the bipartisan proposal by Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin and Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act as an alternative to S. 1, the For The People Act, Democrats’ wide-ranging voting rights and democracy reform package.

At face value, this had an obvious practical significance: Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) has said he’ll only support voting-rights legislation that can overcome a Republican filibuster, and McConnell’s declaration leaves little doubt that the GOP minority will not help Democrats pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

This, in turn, will bolster GOP officials at the state level, many of whom are furiously attacking voting rights and electoral systems in order to tilt the playing field in Republicans’ favor.

But it’s worth pausing to note McConnell’s explanation for his position. “It’s against the law to discriminate in voting based on race already,” the Kentucky Republican told reporters. “And so I think it’s unnecessary.”

At face value, it’s true that states are legally prohibited from passing anti-voting laws that discriminate on the basis of race. We can say this with certainty because of the plain and unambiguous text of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

This was one of the three constitutional amendments added to the Constitution in response to the Civil War. It was approved by Congress in 1869, and took effect a year later. What’s more, let’s not forget — and let’s remind a certain conservative Democrat from West Virginia — that the 15th Amendment was approved by one party, over the objections of the other, because lawmakers were more interested in doing the right thing than the bipartisan thing.

But for segregationists, white supremacists, and other opponents of multi-racial democracy, the 15th Amendment did not prevent voter-suppression laws designed to prevent Black voters from casting ballots. It simply forced segregationists, white supremacists, and other opponents of multi-racial democracy to craft voting-rights policies in discriminatory ways without explicitly racist language.

Voting restrictions from the Jim Crow era, for example, did not literally say, “Black people cannot vote.” Rather, those restrictions were imposed to have those effects without explicitly saying so.

As such, when segregationists were pressed to defend Jim Crow policies, they would point to the 15th Amendment and claim, with faux sincerity, that their voting restrictions were perfectly permissible because they built on statutory language that was race-neutral — practical implications be damned.