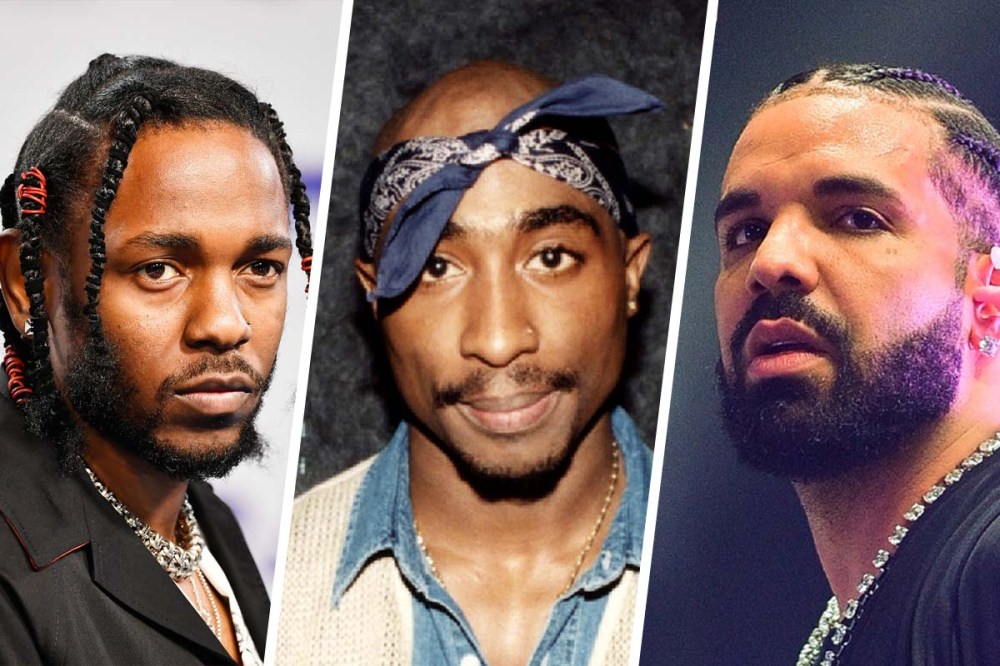

If your Wi-Fi wasn’t out this weekend, then you probably know that it’s been a busy few days for two of the biggest stars in rap music. The back-and-forth rap battle between Kendrick Lamar and Drake got even more intense than it had already been as they made insidious accusations about each other. Lamar and Drake accused one another of illegal and immoral behavior and dipped into the well of rumors to try to humiliate and shame one another.

Kendrick Lamar and Drake have accused one another of illegal and immoral behavior and have dipped into the well of rumors to try to humiliate and shame one another.

The rapid-fire battle crossed the line into the personal many tracks ago. And even though many have found the substance of each emcee’s lyrics to be beyond the pale, the battle itself is bigger than the two of them, and is, instead, a part of a much bigger fight for the soul of hip-hop. It’s the fight between authenticity and commercialism, between the most artfully made hip-hop and the hip-hop that flies off the shelves.

Drake has an entire catalog of hit records. His rhymes are catchy and it’s unlikely that a party, club, wedding or bar/bat mitzvah won’t feature at least a few of his songs. At the same time, perhaps because the biracial Drake is Canadian-born with suburban roots seeped in above-average levels of privilege, he has struggled to be considered authentically hip-hop.

Months ago, when Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def), a hip-hop purist, was asked, “Is Drake hip-hop?” he said, “Drake is pop to me. In the sense that if I was in Target in Houston and I heard a Drake song … It feels like a lot of his music is compatible with — shopping.”

That hilarious characterization of Drake’s music gets at the heart of what many people in hip-hop culture have always felt: that he and his music are inauthentic. While in the middle of this rap babble with Lamar, he helped fuel the accusations that he’s not authentic when he used artificial intelligence-generated voices of the late Tupac Shakur and Snoop Dogg on his song “Taylor Made Freestyle.”

That song, which Drake removed from the internet after Tupac’s estate threatened him with legal action and praised Lamar as “a good friend to the Estate,” was largely seen as creative, but also tone deaf.

On the other end sits Kendrick Lamar. Whereas Drake’s commercial-friendly style and sing-songy lyrics have been the lifeblood of popular consumption, Lamar has built his brand of music as a purist, focusing on complex rhyme schemes, themes ringing of pro-Blackness and putting attention to detail and lyrics over party jams. The respective success of each of these artists illustrates this fairly plainly: Lamar has repeatedly garnered more critical acclaim. He’s won more than three times the number of Grammys Drake has — 17 to 5 — and he even won a Pulitzer Prize for his album “Damn.”

That album, the first hip-hop album to ever win a Pulitzer, was lauded by the selection committee as a “virtuosic song collection unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African-American life.”

But when we’re counting rap stars’ sales, there’s simply no comparison. Drake has outsold everybody. Just like in every genre — books, movies, even TV — there are camps that favor works that considered more layered, genuine and artistic over the bestsellers. It’s just as true in hip-hop.

But when we’re counting sales, there’s simply no comparison. Drake has outsold everybody.

We’ve seen this movie before. In the early 2000’s, Jay-Z and Nas were two of rap’s biggest titans. They, too, clashed in a series of diss records when Nas was largely considered the people’s champ, a commercial underdog whose calling card was complex lyricism and an adherence to hip-hop’s most authentic elements.

Jay Z, on the other hand, although he had come from Brooklyn’s Marcy Projects and had real-life street cred, had nevertheless ascended to a level of commercial success that Nas hadn’t. (Eventually, Jay-Z’s commercial success would lead to him serving as pitchman of his own signature Reebok sneakers and inking a deal with Samsung that provided an advance copy of his album “Magna Carta Holy Grail” via an app available to Galaxy phone users.) It was a battle that pitted hip-hop’s evolution into a global and commercial force against the music’s roots as an authentic sub-culture of urban America.