A visit to a typical New York food pantry is supposed to get you nine meals, enough to last for three days. While the pantry bags may sometimes include fresh produce or fresh bread, most of the items distributed are a little more humble than that: Maybe some canned chicken, some rice, a couple single-serving packets of oatmeal. Some recipients may be able to stretch their monthly allotment further than others, but that bag of food will never be more than a stopgap to get you to the next paycheck, the next round of food stamp benefits, or—in especially desperate times—the next food pantry visit.

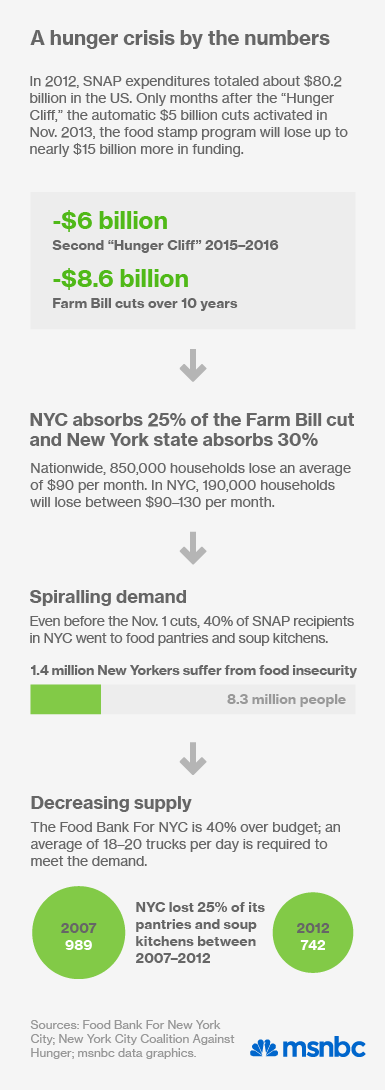

Now, even that short-term safety net is becoming more threadbare than ever. On November 1, a $5 billion automatic cut to food stamp benefits pushed America’s already historic levels of hunger and food insecurity even higher. The result was a sharp spike in the number of people accessing emergency food services.

In New York, the increased demand has been more than many food pantries are able to handle. Over the next month, nearly a quarter of the city’s pantries have had to conserve resources by cutting down on the amount of food they put in each recipient’s bag. Slightly more than a quarter of the city’s food pantries and soup kitchens have begun to turn people away due to lack of food, according to a survey by Food Bank For New York City. Some 522 food pantries and 138 soup kitchens participated in the survey.

Food Bank For New York City’s research looked only at the immediate aftermath of the cuts, but since then the problem seems to have gotten significantly worse. When the food bank held its annual conference on January 15, attended by over 500 representatives of the New York’s food pantries and soup kitchens, “over half of the room said that we’re absolutely rationing the amount of food we give people,” said food bank President Margarette Purvis.

What’s happening in New York is a testament to just how dire America’s hunger crisis has become. America’s most populous city also has what is perhaps the country’s most robust emergency food infrastructure, yet it is still flailing to address skyrocketing food insecurity and greater demand for emergency services. In 2013, Food Bank For New York City—America’s largest food bank—delivered 71 million pounds of food to nearly 750 agencies around the city. Yet the food bank, its member agencies, and hundreds of other organizations providing emergency food assistance around the city, are still finding it impossible to keep up with the growing pace of food insecurity.

“I don’t think it’s ever been the way it is now…It seems like we just see more and more people coming in here,” said Community Health Action of Staten Island executive director Diane Arneth.

In a city of 8.3 million people, as many as 1.4 million residents suffer from food insecurity according to the New York City Coalition Against Hunger’s 2013 Hunger Report [PDF], which uses data from the USDA and adopts the agency’s definition of food security as “access … to enough food for an active, healthy life.” That number is likely to go up before it goes down, advocates say.

Death By A Thousand Cuts

“What’s happened in New York is pretty similar to what’s happened in the rest of the country. Like everything else here, it’s exaggerated and bigger, but the trends tend to be the same,” said Joel Berg, New York City Coalition Against Hunger (NYCCAH) executive director and former advisor to President Bill Clinton. The modern hunger crisis “can be directly traced to the Reagan era and the replacement of living wage jobs with poverty jobs or no jobs at all,” Berg told msnbc.

Federal nutrition programs had expanded dramatically in the decade before President Reagan took office, but his administration put a decisive end to the forward momentum. In a 1983 Christian Science Monitor op-ed called “The return of hunger to America,” Democratic presidential candidate and South Carolina Senator Ernest Hollings noted that Reagan had successfully slashed at least $5.9 billion (or nearly $13.6 billion, in 2014 dollars) out of food stamps.

In the late 70s, hunger in the United States appeared to be nearing extinction. In New York, says Berg, there was so little need for emergency food services that in 1978 the city had only 28 operating feeding agencies. By 2014, that number had ballooned to about 1,000 agencies.

Granted, there was a slight dip in nationwide food insecurity figures during the boom times of the late 90s and early aughts, according to USDA figures. Yet the brief dip didn’t last long, thanks in part to President Clinton’s 1996 welfare cuts and the lack of any concerted federal anti-hunger effort.

The 2008 financial collapse vastly hiked the number of hungry people in New York and across the U.S. Between 2006 and 2012, according to NYCCAH estimates, roughly 200,000 New Yorkers became food insecure. To make matters worse, the same economic forces that added those 200,000 to the ranks of the needy also decimated the non-profit safety net which was supposed to catch them. Between 2007 and 2012, New York lost 25% of its food pantries and soup kitchens.

The 2009 federal stimulus bill helped to limit the damage by adding back $45.2 billion to the food stamp program and raised the cap on maximum benefits. Yet food insecurity never returned to pre-recession levels, and November’s $5 billion cut wound up making things worse.

In fact, the Food Bank For New York City reports that its member pantries and soup kitchens saw a greater increase in demand as an immediate result of the food stamp cuts than they did in the weeks after Hurricane Sandy slammed the city in 2012.

Now another cut is coming. President Obama recently signed a law that will cut food stamps by an estimated $8.6 billion over the next 10 years. The cuts, which eliminate “Heat and Eat” policies in 15 states and Washington, D.C., will cause 850,000 households around the country to lose an average of $90 per month. Roughly 190,000 of those households are in New York City alone.

The day before Obama signed the law, Berg held a NYCCAH staff meeting where he said “people were practically in tears thinking about what’s going to happen.”

“We’ve been socialized in America expecting some sort of Frank Capra-esque happy ending, or that somehow we’re going to cope…That’s just not the case,” said Berg. “People are going to suffer more.”

“It’s Going to Be Chaos”

If New York were a country, then Staten Island would be the closest thing it has to a red state. The city’s so-called “forgotten borough” is also its whitest and its most conservative; plus, it has a higher median household income than Manhattan. Yet the island also has its pockets of desperation: Isolated, poorer neighborhoods, occupied largely by people of color.

Community Health Action of Staten Island (CHASI) does what it can to feed those neighborhoods. For years, the non-profit has operated a food pantry along the north shore of the island, in the predominantly low-income neighborhood of Port Richmond. CHASI’s pantry is a “client choice” location, meaning that clients get to choose between different kinds of bread, produce, cereal, and so on.

The pantry also provides assistance in filling out applications for food stamp benefits—something that Food Bank for New York City now strongly encourages all of its member pantries to do, as part of its “all of the above” strategy for dealing with hunger. Yet even coaxing hungry people to ask for federal assistance can be a challenge in the city’s most conservative borough.

“There’s that stigma there that prevents a lot of people from even taking that first step of coming here,” CHASI executive director Diane Arneth told msnbc. Staten Islanders who are new to food insecurity will often flatly refuse to sign up for food stamps if they are referred to by that name; instead, CHASI urges its staff and volunteers to refer to the benefits program by its more recent moniker, SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program).

Many of CHASI’s regulars are already signed up for SNAP and other forms of government assistance. Several of the people msnbc encountered while visiting the pantry were also on federal disability benefits, for reasons ranging from difficulty walking to mental illness. The disabled and elderly are expected to be disproportionately affected by the most recent $8.6 billion cut to food stamps.

David Atkinson, 66, is among the pantry regulars who rely on disability benefits. He said he has been unable to work since his wife died about five years ago, leaving him with crippling depression. They had been living in North Carolina when she passed away, after which Atkinson returned to his hometown of New York, where he knew he could navigate the local welfare system well enough to survive.