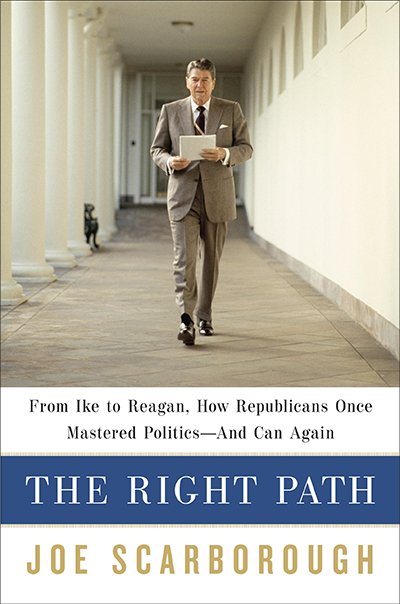

Host Joe Scarborough’s latest book hits shelves Tuesday.

Foreword“It was invisible, as always. . . . On election day America is Republican until five or six in the evening. It is in the last few hours of the day that working people and their families vote, on the way home from work, or after supper; it is then, at evening, that America goes Democratic if it goes Democratic at all. All of this is invisible, for it is the essence of the act that as it happens it is a mystery in which millions of people fit one fragment of the total secret together, none of them knowing the shape of the whole.”—Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1960

In Theodore White’s now canonical telling of the legend, the sacred democratic ritual begins as silently as snow falling on a serene New England landscape. His beautiful rendering of America’s political system offers a comforting image of a peaceful process that reveals itself to a citizenry that rises the morning after an election to gaze wondrously upon the glorious results of their efforts, like watchful children awakening to winter’s first snowfall. The beauty of the voting booth, seen through the lens of Teddy White’s inspiring works, is how our glorious Republic moves forward.

Except when it doesn’t. In those moments when a cultural shift is so sharp and sudden that its impact jars the political class out of a deep slumber, there is nothing gentle, nothing amiable about politics. These moments are more Norman Lear than Norman Rockwell, and the aftershocks seem all the more violent because few ever see a great political unraveling coming until after a Washington coalition crumbles and consensus disintegrates into cacophony.

This book tells the story of the unexpected rise and self-inflicted fall of the modern Republican Party, a movement that found a path to power in the middle of the 1960s and went on to dominate American life for forty years. With the national Grand Old Party seemingly on a glide path to ideological and demographic irrelevance as a presidential force, it’s difficult to remember, but we used to be the ones to beat. From 1968 to 2008, Republicans lost only when Democrats took care to sound more conservative than liberal. Between Richard Nixon and Barack Obama, the only Democrats to win the presidency of the United States were two white Southern Baptists who sought office by positioning themselves as nontraditional Democrats who understood the failings of liberalism and appreciated the virtues of conservatism. Republicans were not beyond the mainstream of American politics. For that forty-year period, Republicans were the mainstream of American politics.

But as conservatives endure two terms of Barack Obama and face the possibility of eight more years with a Clinton in the White House, all too often these days it’s the Republicans who sound angry, extreme, and too out of touch. If the GOP wants to regain its place as the decisive force in national politics, it needs to reengage with its real legacy, which is one of principled conservatism combined with clear-eyed pragmatism. We Republicans have been at our best when we are true to one of the deepest insights of conservatism: that politics, like mankind itself, isn’t perfectible in a fallen universe. And if we continue to let the perfect become the enemy of the good, then we will continue to dwindle in influence.

The good news is that the GOP’s ongoing decline as a national party is not inevitable. History tells us, actually, that we’re pretty good when the odds are the longest. Republicans emerged from what seemed an invincibly liberal political culture in the middle of what Time founder Henry Luce called the American Century when Lionel Trilling suggested that “in the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition.” Trilling, one of America’s foremost mid-century literary critics, dismissed conservative thought as little more than “irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.” History proved Trilling’s quote to be as untimely as the one uttered by a British record executive who told the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein, that bands with guitars were on their way out.

Conservatism would ultimately rise, not through “irritable mental gestures” or by being nativist or racist or blindly ideological. No, the party succeeded in direct proportion to its respect for overarching ideas about the nation and about the world that had a practical impact on the lives of Americans. Dwight Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan dominated the ideological middle of American thought because these GOP giants won elections by putting principled pragmatism ahead of reflexive purity.

Note that I say principled pragmatism: like our greatest leaders of any stripe—Washington, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, TR, FDR, JFK—Republicans of the modern era, driven by conservatives, reso¬nated with a majority of Americans when they demonstrated a gen¬uine commitment to the ideas of greater liberty, a restrained state, social order, and strength abroad. These are the key conservative principles that most Americans agree with, have always agreed with, and will agree with in the future. Republicans who try to use the power of the state to interfere in matters of personal liberty will be as doomed as the big-government Democrats who wanted to use the authority of government to impose a singular “Great Society” on all of America. Conservatives know that the world is made up of what Edmund Burke described as “little platoons”—the small towns or the city neighborhoods where happiness is pursued.

The right path to power lies in appreciating that politics isn’t a science but an art—that America has been at her best and will be again when the common wisdom of the people, carefully weighed in the Madisonian scales of the Constitution, has a prime place in the governance of the nation. And history shows that the common wisdom of the people is essentially conservative in that most people want to find the right balance between freedom and responsibility.

For Eisenhower and Reagan, the two great leaders of the modern Republican Party, restraint both at home and abroad were the philosophical foundations of their presidencies. Both saw their first challenge as limiting the federal government’s ever-expanding reach at home. Ike’s presidency followed twenty years of New Deal activism, while Reagan’s focus was on reversing the more destructive, unintended consequences of LBJ’s Great Society. These two Republicans won four landslide victories between them because they were also shrewd enough to yield to immovable political realities that even their landslide victories could not wash away.