American intelligence officials and their supporters in Congress agree: the controversy over the National Security Agency’s surveillance program is the media’s fault.

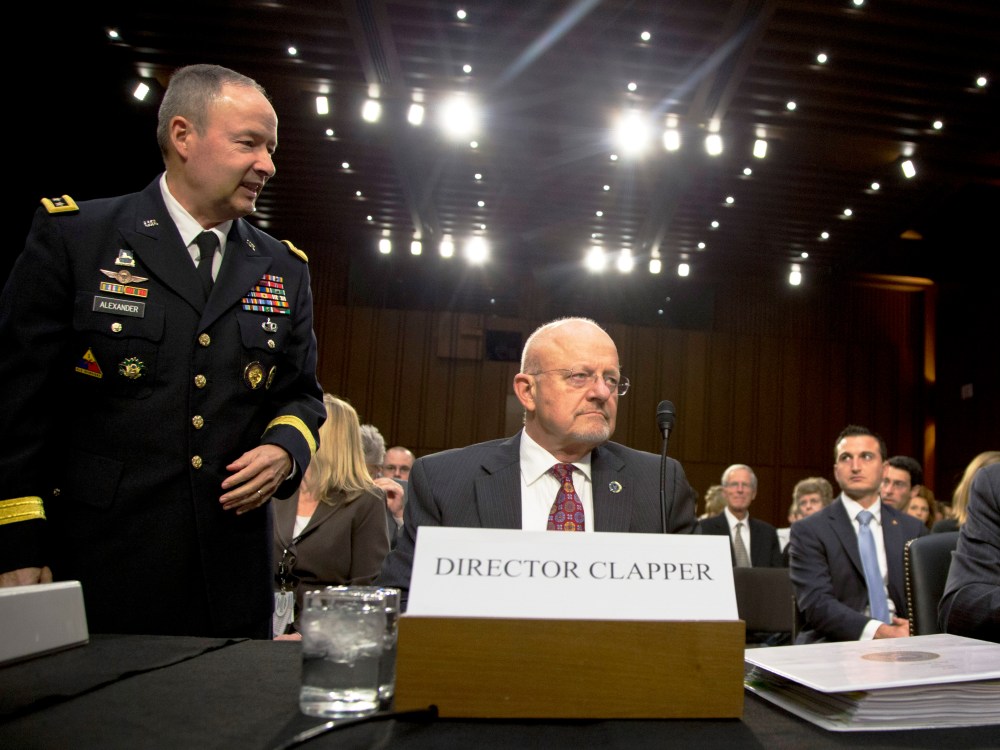

“In the last few months, the manner in which our activities have been characterized has often been incomplete, inaccurate, or misleading,” James Clapper, director of national intelligence told the Senate intelligence committee Thursday. “This public discussion should be based on an accurate understanding of the intelligence community: who we are, what we do, and how we’re overseen.” General Keith Alexander, Director of the National Security Agency, likewise slammed “sensational” reporting on government surveillance powers. Republican Senator Dan Coats of Indiana complained of a “non-trusting public” fired up by a press that’s eager to “throw raw meat out there.”

California Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein, the intel committee chair, said that the NSA’s surveillance program wasn’t even a surveillance program at all. “Much of the press has called this a surveillance program. It is not, and the general belief out there is that everyone is being surveilled, and they are not,” Feinstein said. Clapper expressed his willingness to work with Congress on reforming surveillance law, but warned that “if it’s transparent for the American people, it’s transparent for our adversaries too.”

The intelligence community leaders’ complaints essentially amount to a dispute over language. A secret court order leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden in June showed that the NSA had sought and been granted access to the communications data of all the customers of a Verizon subsidiary. Similar orders are in place for other telecommunications providers. During Thursday’s hearing, Alexander insisted that collecting so many records is necessary to create a “haystack” through which to search for the needles of terrorist communications. When Colorado Democratic Senator Mark Udall asked Alexander if the NSA sought all Americans’ communications records, Alexander said the NSA should “put all the phone records into a lockbox that we can search when the nation needs to do it.”

So there’s little dispute that Americans’ communications data are being collected—or that the NSA is interested in collecting as much as possible. The intelligence leadership and its Congressional backers argue that the NSA doesn’t actually look through the massive database except when the agency has “reasonable articulable suspicion” to justify doing so, and therefore, Americans’ privacy is protected.

Critics of the law counter that Americans’ rights are violated when the government collects the data in the first place. During the hearing, they pointed out that, contrary to the intel chiefs’ complaints about misleading press coverage, the intelligence leadership had mislead the public about the nature of government surveillance prior to the leaks.