Springfield, Mass. — Elizabeth Warren says inequality is a fundamental problem, and that it’s up to the government to do something about it. But her home state of Massachusetts—friendlier than most to an active and involved government—remains the site of some of the country’s starkest disparities.

Kicking off the first leg of her book tour at Harvard, Sen. Warren assured the Cambridge crowd that she has a plan to help Americans pay for college.

“I’m going to introduce a bill next month to refinance outstanding student loan debt to bring it down so that students have a better chance to get an education,” she announced proudly.

But 80 miles across the Mass Pike in Springfield—where the poverty rate is more than 2.5 times the state average—there’s an even more basic gap that needs to be bridged.

Genelle Domino, 24, dropped out of high school her junior year when she was stuck in foster care. Chronically unemployed in a place where the jobless rate still tops 11%, she decided to go back to school to get her GED—only to be told there was no room for her in any of the free public programs.

“It seemed like nobody was ever gonna call me,” says Domino, who sat at home “going crazy” in between odd jobs. “I was like, ‘I don’t even know—I don’t think I want to get back to school anymore.’”

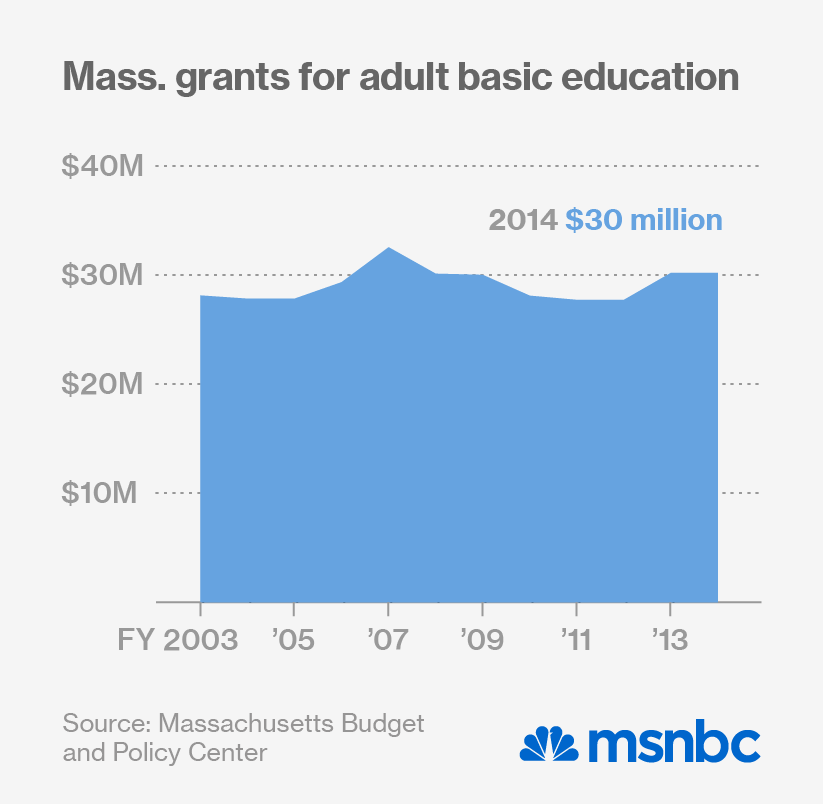

Domino’s experience is hardly unique: In Massachusetts alone, there are more than 17,400 people currently on the wait list for the state’s adult basic education classes—and hundreds of thousands more across the country.

“You have all these people who want to work—who have really high success rates if they get into a program—but there’s no funding for them,” says Bob LePage, interim director of the Springfield Technical Community College Foundation. “So we have all these people who are left behind.”

Because of federal funding cuts and a tight state budget, it took almost two years for a spot for Domino to open up. In February, she finally got into an adult basic education course she hopes to finish this summer.

The broad federal cuts known as sequestration are still in effect for adult education—one of the few education and training programs that didn’t have its funding restored by Congress’s most recent budget, says Marcie W.M. Foster, a senior analyst for the Center for Law and Social Policy.

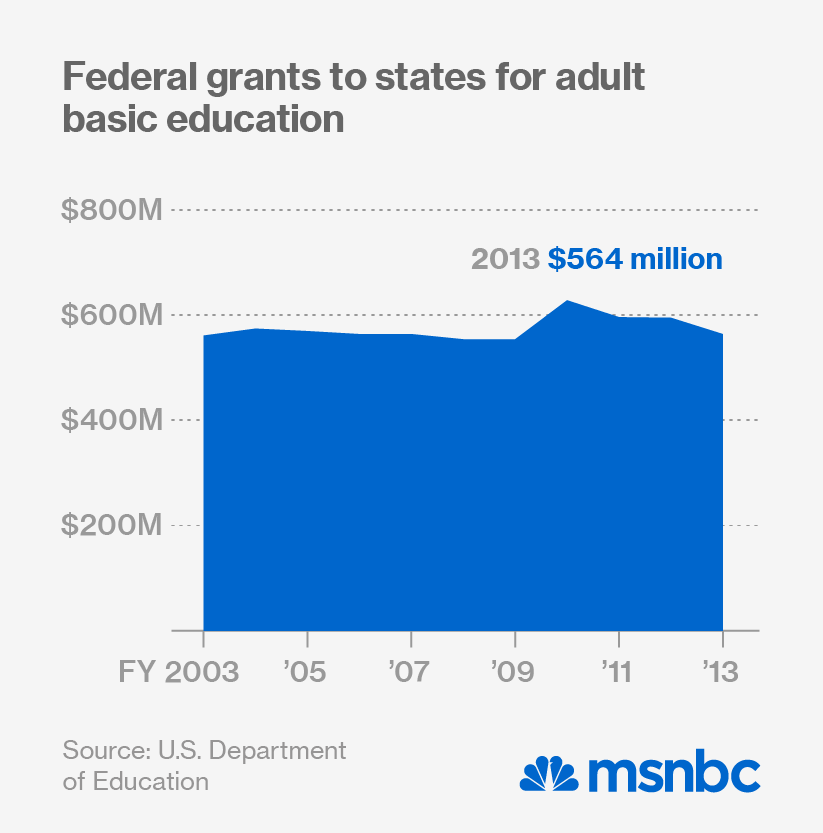

Federal funding for adult learners has already been falling for years, even before the sequestration cut took effect in 2013—a reduction of about $50 million, according to New America Foundation analyst Mary Alice McCarthy.

State and local governments have struggled to make up the difference: Facing a budget gap, Florida started charging tuition in 2011 for such classes, which has since depressed enrollment. “We’re about 1.8 million students served by the federal system— down from about 3 million just a few years,” Foster says.

Like most Democrats, Warren supports more federal money for what she broadly describes as “investments” in infrastructure and education. But like most politicians, when she discusses the problems facing ordinary Americans she mostly focuses on the middle-class and students who’ve already made it to college.

In her new book, “A Fighting Chance,” she recalls one early supporter in New Bedford, who “laid out her life in just a few sentences: I have two master’s degrees. I’m smart. I taught myself computer programming. I’ve been out of work for a year and a half.” She describes another supporter at a campaign stop in Worcester. “Counting on his fingers, he punched out the list. Worked hard in high school. Went to a good university. Got good grades. Graduated on time. Everything—check, check, check. And then … nothing. No job.”

Many at Warren’s recent events seem to come from a similar world. The day after speaking in Cambridge, Warren traveled to Springfield Technical Community College, speaking in a gym just a few doors down from where Domino studies algebra and reading comprehension. Nearly 90% of STCC’s adult basic education and ESL students are minorities, with an average age of 27, reflecting the surrounding city. But the crowd at the event that night was largely white, middle-aged and professional, including a small business owner from Stockbridge, teachers from Northampton, and a library worker from Amherst.

Warren’s audience had concerns about Springfield’s future, too. But they didn’t raise them during the event itself, where the questions ranged from French economist Thomas Piketty’s new book on inequality to the senator’s political aspirations.

“I was going to ask her, ‘What will it take to get Springfield out of the hole?’” said Selina Kell, 51, a Latin teacher from Northampton, while waiting for Warren to speak. But after consulting with her journalist sister, Kell decided to ask another question instead: “What will it take to convince you to run for president in 2016?”

When msnbc posed Kell’s original question to her after the event, Warren gave her standard response.

“Springfield has enormous potential. But we need to make investments in education and infrastructure here just to give people a fighting chance,” she said, dropping the title of her new book.

Springfield, certainly, has heard such vows before. The city was once one of the country’s most prominent manufacturing hubs and has suffered the same decline as much of America’s Rust Belt. STCC’s very campus is on the site of the old Springfield Armory, which produced military firearms for 200 years before closing in 1968.

Despite decades of promises to “reinvent” Springfield, the city slid into poverty and high unemployment, its once flourishing downtown now blighted by boarded up factories and decaying Victorian mansions. It nearly collapsed in 2004 when an incompetent and corrupt local government racked up a $40 million budget deficit.

But other policies have also hastened the city’s decline.

“Springfield is home to several important institutions of higher education, but has not made as much progress as many of its peer cities in improving the educational attainment of its residents,” concluded a 2009 paper from the Boston Federal Reserve Bank.

“The inequality comes down to the educational achievement gap,” says Michael Goodman, chair of the public policy department at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth.