The funny thing about a dog that chases a car? Sometimes it catches the car and has no idea what to do next.

Over the last several days, members of Congress have spoken out with a variety of opinions about U.S. policy towards Syria, but lawmakers were in broad agreement about one thing: they wanted President Obama to engage Congress on the use of military force. Few expected the White House to take the requests too seriously.

Why not? Because over the last several decades, presidents in both parties have increasingly consolidated authority over national security matters, tilting practically all power over the use of force towards the Oval Office and away from the legislative branch. Whereas the Constitution and the War Powers Act intended to serve as checks on presidential authority on military intervention abroad, there’s been a gradual (ahem) drift away from these institutional norms.

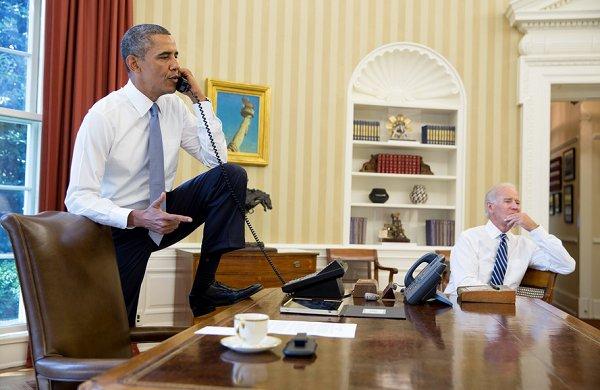

That is, until this afternoon, when President Obama stunned everyone, announcing his decision to seek “authorization” from a co-equal branch of government.

It’s one of those terrific examples of good politics and good policy. On the former, the American public clearly endorses the idea of Congress giving its approval before military strikes begin. On the latter, at the risk of putting too fine a point on this, Obama’s move away from unilateralism reflects how our constitutional, democratic system of government is supposed to work.

Arguably the most amazing response to the news came from Rep. Peter King (R-N.Y.), the chair of the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Counterintelligence & Terrorism, and a member of the House Intelligence Committee:

“President Obama is abdicating his responsibility as commander-in-chief and undermining the authority of future presidents. The President does not need Congress to authorize a strike on Syria.”

This is one of those remarkable moments when a prominent member of Congress urges the White House to circumvent Congress, even after many of his colleagues spent the week making the exact opposite argument.

The next question, of course, is simple: now that Obama is putting Congress on the spot, what’s likely to happen next? Now that the dog has caught the car it was chasing, what exactly does it intend to do?

Lawmakers, in theory, could cut short their month-long break, return to work, and consider their constitutional obligations immediately. That almost certainly won’t happen, at least not the lower chamber — as my colleague Will Femia reported earlier, House Republican leaders have said they’re prepared to “consider a measure the week of September 9th.” There are reports Senate Democratic leaders may act sooner, but no formal announcement has been made.

The dirty little secret is that much of Congress was content to have no say in this matter. When a letter circulated demanding the president seek lawmakers’ authorization, most of the House and Senate didn’t sign it — some were willing to let Obama do whatever he chose to do, some didn’t want the burden of responsibility. Members spent the week complaining about the president not taking Congress’ role seriously enough, confident that their rhetoric was just talk.

It spoke to a larger problem: for far too many lawmakers, it’s so much easier to criticize than govern. In recent years, members of Congress have too often decided they’re little more than powerful pundits, shouting from the sidelines rather than getting in the game.

It’s one of the angles to today’s news that’s so fascinating — Obama isn’t just challenging Congress to play a constructive role in a national security matter, the president is also telling lawmakers to act like adults for a change. They’re federal lawmakers in the planet’s most powerful government, and maybe now would be a good time to act like grown-ups who are mindful of their duties.