The Congressional Budget Office says that increasing the minimum wage would eliminate half a million jobs. But the consensus among economists is that increasing the minimum wage would eliminate few if any jobs. Who’s right?

In part, this is a dispute between analysis and observation. CBO is projecting what ought to happen based on economic modeling. The consensus among economists is based on what’s actually been observed to happen.

For many decades, economic textbooks–following the orthodox view enunciated by, among others, the Chicago-school Nobel prizewinner George Stigler in 1946–said that raising the minimum wage would always cost the economy a significant number of jobs. The New York Times editorial page, in a mad moment, went so far as to propose in 1987 that the minimum wage be eliminated! But starting in the early 1990s, economists began noticing that those big predicted job losses weren’t actually, um, happening.

The most influential of these studies, by economists David Card (Berkeley) and Alan Krueger (Princeton, and until recently chairman of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers), appeared in 1994. Card and Krueger surveyed 410 fast-food restaurants in New Jersey, which raised its minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05, and eastern Pennsylvania, which kept its state minimum wage at $4.25. The Gospel according to Stigler dictated that New Jersey’s 19% minimum-wage hike ought to have put fast food employees out of work. But no job loss was observed. Indeed, relative to eastern Pennsylvania, fast-food jobs increased slightly.

This bolstered earlier research by Card, Krueger, and Harvard’s Lawrence Katz that similarly found no job loss among teenage and fast food workers in California and Texas after the federal government raised the minimum wage 25%, from $3.80 to $4.75, in 1990 and 1991.

Why didn’t these minimum wage increases kill jobs? Partly because fast food joints raised prices to cover the increased cost of hiring; partly because a higher minimum wage meant less turnover, and therefore fewer resources diverted to hiring; and partly because a higher minimum attracted better employees (or perhaps motivated the same employees to become better).

Does that mean a minimum-wage increase will never eliminate jobs? Of course not, says Katz. If the minimum were raised as high as $15 per hour–as fast food protesters are currently demanding–“I would very strongly worry that there would be really large displacement effects.” (Not that these workers can be faulted for seeking $15; in politics, ask for $15 and you’ll maybe get $10 or $12.)

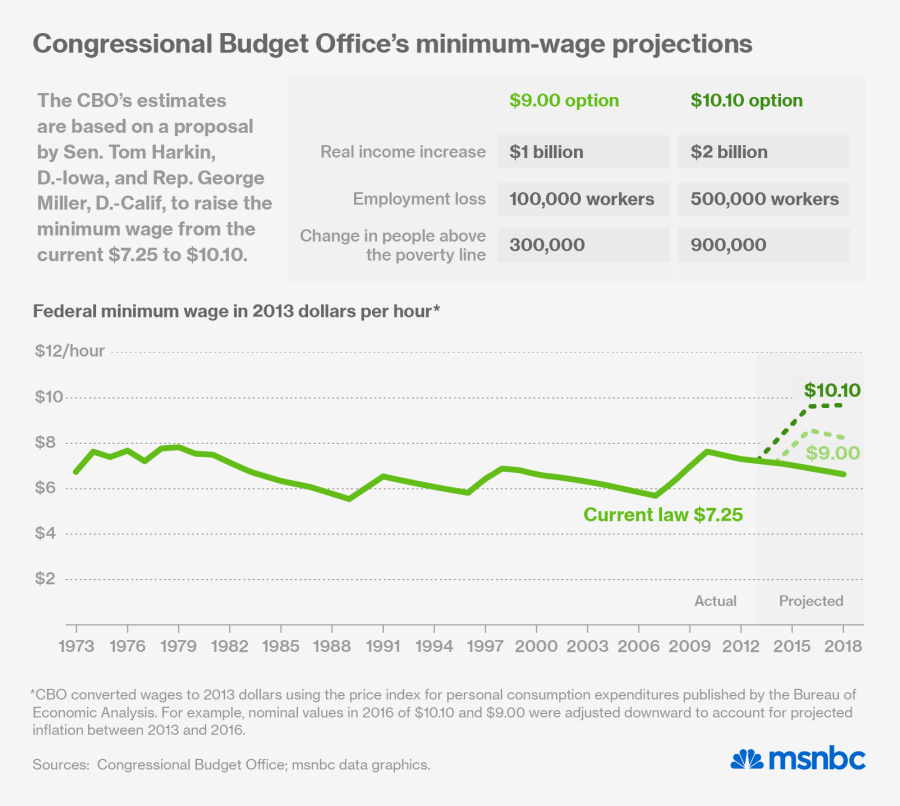

The CBO’s calculation that a minimum-wage increase would cost 500,000 jobs is based on a proposal by Sen. Tom Harkin, D.-Iowa, and Rep. George Miller, D.-Calif, to raise the minimum wage from the current $7.25 to $10.10. That’s a 39% increase, which is fairly big. Moreover, inflation hasn’t eroded the buying power of the current minimum wage, last increased in 2009, as much as it had when the federal minimum was raised in the early 1990s or in 2007. In those earlier instances, a decade had passed since the previous increase, and the economy had expanded much more than it’s been doing lately. The impact of raising the minimum wage to $10.10 would therefore be greater (especially considering that it would henceforth increase with the cost of living—a proposition so dangerously socialistic that it’s been endorsed by Mitt Romney).

How much greater that impact would be is a source of legitimate disagreement. “They’re not doing anything that’s outside the range” of reasonable discussion, says Katz of the CBO calculations, a point echoed by Jared Bernstein of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Georgetown’s Harry Holzer. Katz and Bernstein say 500,000 is at the very high range of reasonable, while Holzer (who supports the increase to $10.10 but is less sanguine about its employment effects) thinks 500,000 is about right. The point is, we don’t know, because it’s a projection.

Jason Furman, Krueger’s successor as chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, is more critical of the CBO study. “These estimates,” he wrote in a blog post, “do not reflect the overall consensus view of economists which is that raising the minimum wage has little or no negative effect on employment.” But even Furman is measured in his criticism of the CBO report. Why?

Three reasons:

1.) No politician or government official is free to say this, but—shhh!–even CBO’s projection of 500,000 jobs lost is not very high. During 2013, the economy added 194,000 jobs per month, a rate of increase that everybody agreed was bad. If the economy were to lose 500,000 jobs, that would equal the number of jobs created during less than three months of distressingly weak economic growth. “Relative to a stronger macro economy that is nothing,” says Katz. “A tight labor market would overwhelm [that] in terms of what it would do for disadvantaged workers.”