ALAMO, Texas — There is no more birth control at the flea market. And if there ever were abortion pills, they’re long gone, too.

At the Rio Grande Valley’s biggest outdoor market, known as la pulga, locals can buy car parts and fertilizer, watermelons out of a pickup, a parakeet, an iPhone case or stickers from their favorite Mexican fútbol team. But since this flea market was among several raided last August over suspicion it was selling abortion pills, if you even ask for birth control you’ll hear voices lower to a fearful whisper. You’ll be sent to the vendor who sells nuts, or the women selling jewelry.

On a recent afternoon, all those destinations were a dead end.

“Not anymore,” a woman whose table bore aspirin and homeopathic remedies said in Spanish. She shrugged. “Obama wants us to have more babies.”

%22Go%20to%20Mexico%20%E2%80%93%20or%20stay%20pregnant.%22′

In fact, it wasn’t the federal government that raided four flea markets’ thriving illegal pharmaceutical trade, making undocumented residents that much more terrified to shop in them. The Sheriff of Hidalgo County, who took the lead, didn’t find any abortion pills, but he did charge nine people with selling prescription-drug contraband like diet pills and Viagra from Mexico. (The border is just minutes away.)

It had been a month-long investigation, Sheriff Lupe Treviño told local press.

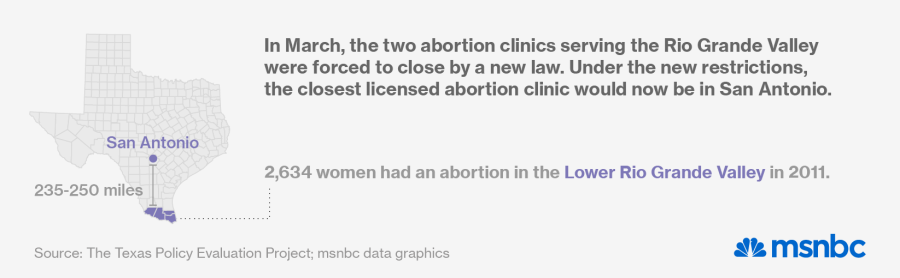

The arrests came a month to the day after a front page New York Times story about how the state’s new omnibus law restricting abortion — the one Texas state Sen. Wendy Davis famously tried to block — was expected to close the Rio Grande Valley’s two abortion clinics. Locals told the paper that with the nearest clinic now 250 miles away, more women would terminate their pregnancies on their own by taking black-market abortion drugs. Such pills, known as misoprostol, are readily available over the counter in Mexican pharmacies. But a trip across the border would cost the undocumented much more.

“The only option left for many women will be to go get those pills at a flea market,” local organizer Lucy Felix had warned.

For many reasons, women had already reportedly been buying pills at flea markets to end their pregnancies – because it was cheaper than going to a clinic, because they feared immigration authorities, or perhaps because they assumed abortion in the U.S. was illegal, as it is in Mexico. They also went to the flea markets for contraception, like birth control pills or injectable Depo-Provera.

As expected, the two local abortion clinics were shuttered in March under the new law — clinics that together performed 2,634 abortions in 2011. And the flea market raids had done their job. There are no abortion pills there, and no hormonal contraception.

The combined crackdown by state and local authorities in Texas has done more than make it harder for the women of the Valley to get an abortion. They’re now having trouble getting any reproductive health care at all, since the same state legislature that shuttered the abortion clinics also slashed family planning funds and closed family planning providers. And Texas’ refusal to expand Medicaid means its distinction as the uninsured capital of the United States isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, making the state’s broader health care crisis even worse.

At la pulga, a woman whose stall had just barely survived the raid had one more idea for obtaining abortion pills.

“Go to Mexico,” she said. “Go to Mexico — or stay pregnant.”

—

%22If%20I%20hadn%27t%20planned%2C%20I%20would%20have%20had%20at%20least%208%20kids.%22′

Marlena, 32, knew all about the raids on la pulga, because that’s where she used to buy her birth control. On a recent Wednesday, most of the women visiting the local San Juan Community Center, where Planned Parenthood has managed to keep open a once-weekly health clinic, had heard about the raids. Some of them said they had always been afraid to buy contraception there, because who knew how long the drugs had been sitting out in the sun?

Marlena said the drugs available at the flea market were just as good as those that her friends sometimes buy for her at pharmacies in Mexico. (She is undocumented.) The only trouble she has is finding someone to inject the Depo-Provera. “No one ever wants to do it,” she said. “They’re afraid of messing it up.”

Claudia, also 32, shook her head. “It’s better to be checked by a doctor,” she said. But she hadn’t seen a doctor since the birth of her youngest three years ago. She’d come to the clinic this time for a breast exam and a pap smear.

“If I hadn’t planned, I would have had at least eight kids,” said Marlena. The youngest of the four children she does have clambered at her feet. “But sometimes you have the money, and sometimes you don’t.” Her husband is a carpenter, and when it rains, there is little work.

It had taken both of them months of calling to get an appointment at the clinic. That Wednesday morning, a four-hour wait past the scheduled time to see the single nurse practitioner wasn’t a surprise. The women patiently juggled each other’s babies on their laps. Quiero cuidarme, they said of their need for birth control. I want to take care of myself.

Much as they’ve tried, they haven’t always been able to do that. One woman at the clinic has nine children. Both Claudia and Marlena want to get their tubes tied, but neither can afford it. “I’ve been on the waiting list for two years,” Marlena said.

In 2010, Planned Parenthood of Hidalgo County, which covers much of the vast Rio Grande area, saw 24,000 patients, including at the San Juan center. Then came the Republican legislature.

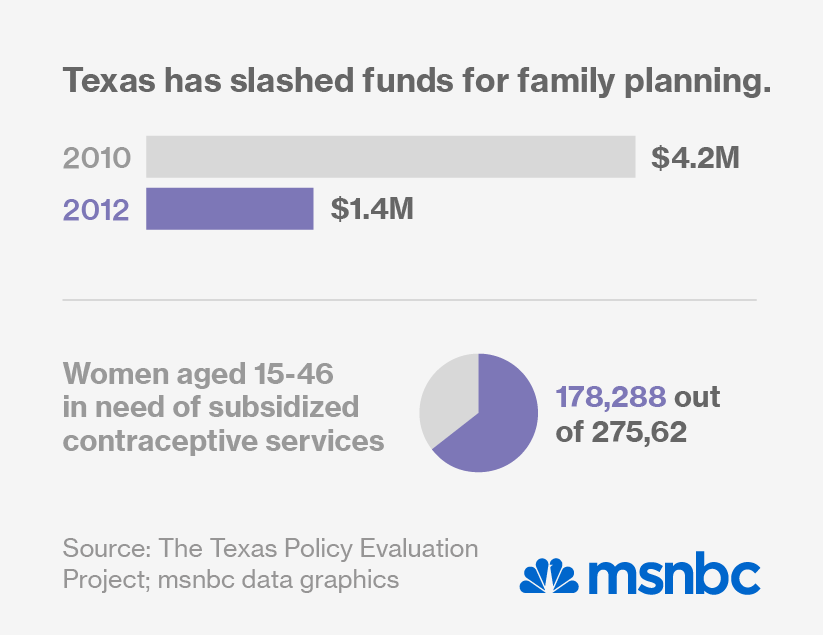

“Sixty-six percent of the funds were slashed completely and given to other programs that don’t do family planning — worthwhile programs, but they’re not for women, especially not poor and uninsured women,” said Patricio Gonzalez, the CEO of Planned Parenthood of Hidalgo County.

That funding cut was followed by state legislation, heralded by Gov. Rick Perry, intended to stop Planned Parenthood from receiving any public funds. The Hidalgo County affiliate had never provided abortions — in fact, public health experts estimate it had prevented between 1,000 and 1,500 abortions a year with its family planning services — but it was doomed by its connection to national Planned Parenthood and its willingness to make referrals to Whole Woman’s Health, the now-shuttered abortion clinic in town.

The family planning money that was left after the funding cuts was divided into three tiers that put Planned Parenthood and other explicitly-pro-choice providers at the very bottom, even though none of the funds were going to abortion services. The county health departments and federally qualified health centers that were supposed to replace Planned Parenthood are already overwhelmed by providing primary care, and they don’t specialize in family planning.

“They’ve destroyed the infrastructure we had here for healthcare,” said Gonzalez. “To cut out the family planning funds was a very cruel thing to do.”

In all, the clinic had to lay off more than half its staff and cut its patient load in half. By October 2011, four of the eight health centers the clinic ran were forced to close.

A small trickle of funds has since been restored through the federal government’s Title X program, which granted $1.1 million for the Rio Grande Valley through a new state association.

“I believe they did not like that the state was taking away access from women,” Gonzalez said of the federal government’s decision to bypass the state.

On top of the uphill struggle to provide basic services like contraception, cancer screenings, and testing for sexually-transmitted infections, Gonzalez is looking to help women who need an abortion. He and his staff have been trying to find an abortion provider who has local admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles — the requirement the state imposed last summer, even though major medical organizations say it has no basis in medical necessity and is only meant to shut down safe clinics.

%22To%20cut%20out%20the%20family%20planning%20funds%20was%20a%20very%20cruel%20thing%20to%20do.%22′

And that’s exactly what happened. Both Whole Women’s Health in McAllen and Dr. Lester Minto’s clinic in nearby Harlingen tried to get those admitting privileges, but were both forced to close after being unable to comply. (Many hospitals didn’t even bother to respond to the clinics’ requests, said Fatima Giffords of Whole Woman’s Health.)

If nothing else, Gonzalez hopes to add a doctor for miscarriage management and to treat women who self-induce an abortion and are still bleeding. Those women used to go to the abortion clinics when their attempts to end their pregnancy on their own failed. One study found that women in the Rio Grande Valley were far more likely than other women nationally to self-induce — 12 percent, compared to the national average of 2.6 percent. And that was before the legal clinics closed.

“It worries us a lot,” said Lucy Felix, a field organizer in the Valley with the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health. “They will find a way to acquire that service, so it’s important to us that there are safe clinics for them to get care.” She knows the stories of women self-inducing — “they are very sad, but I can’t tell them.”

The fear isn’t just breaking the fragile trust of the women who come for health and education — it’s that the women could even be prosecuted.

These women are already struggling to get basic health care services, Felix pointed out. She was taking a break from a baby shower at a colonia, one of many unincorporated settlements where the poverty can be desperate.

“Many colonias don’t even exist on the map,” she said. “The GPS can’t find them, so how can programs and resources?”