They’re supposed to be the lucky ones.

While the long-term unemployed have been running out of luck, those who’ve been searching for work for just a few weeks are returning to the labor force at a steady clip.

The number of those unemployed for less than five weeks has fallen to 2007 lows. Those who’ve been out of work for up to 26 weeks are finding it easier to get a job, and most still qualify for state unemployment benefits. By comparison, the number of long-term unemployed is still at a historic high.

But new research reveals a more troubling portrait of the labor market—even for those who’ve who managed to find work again in a relatively short amount of time—indicating that the scars of the Great Recession will be deeper than we think.

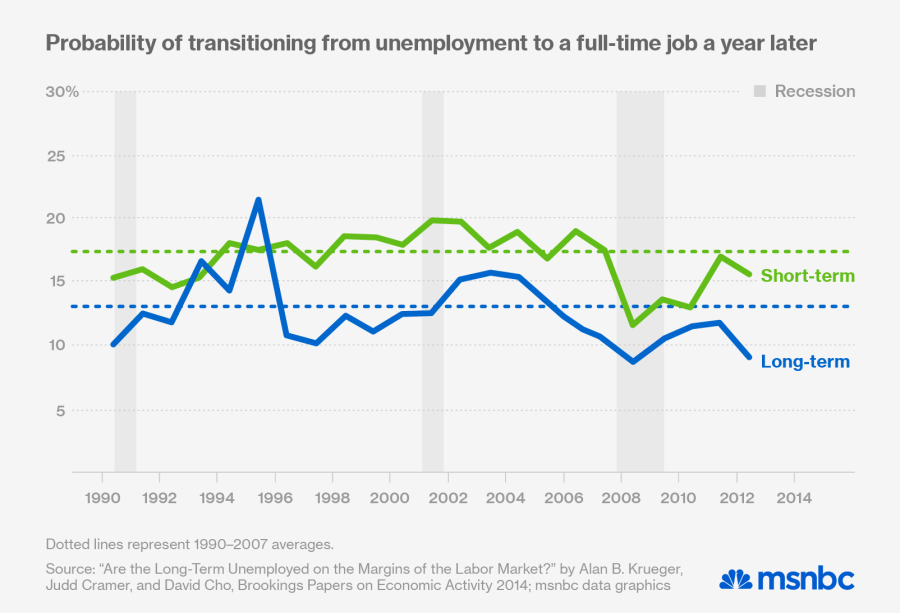

Since the beginning of the downturn, about 50% of those who were short-term unemployed at any given time were found to be working a year later. But only about 15% were at steady full time jobs, according to a paper by co-authored by former Obama economic adviser, Alan Krueger, Judd Cramer, and David Cho, all of Princeton University. The rest either became long-term unemployed, got part-time, short-lived or otherwise temporary jobs, or stopped looked for work altogether.

Those are still better prospects that those facing those who were long-term unemployed during those four years: Just about 11% of them were working steady jobs a year later. But it’s been a long climb back for both groups.

“I went from making $54,000 a year, to making $11 an hour,” says Linda Gibson, 57, who lost her job of 11 years as an executive assistant in 2009. It had taken Gibson five months to find part-time work as a law firm assistant; she had to supplement her income by working at a cashier at Boston Market in the Los Angeles area.

All this suggests there’s less of a difference between the short- and long-term unemployed than we might think. “It’s not like you end up being out of work for X weeks, and you’re screwed,” says Katherine Abraham, a professor at the University of Maryland and a former member of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. The main difference seems to be one’s willingness to take stopgap work, however temporary and low-paying.

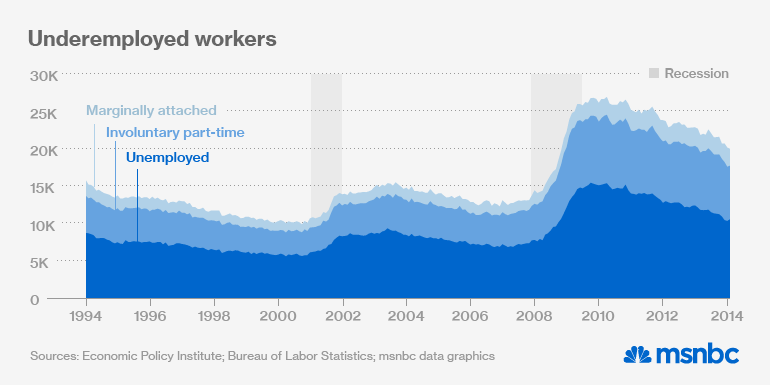

The face of the jobs recovery suggests as much. Many of the new jobs being added are in low-wage sectors like leisure, hospitality, and retail. Temp work has increased 28 percent since 2010—compared to 5 percent for all jobs—employing more than 2.9 million Americans last year, according to new analysis from CareerBuilder and Economic Modeling Specialists Intl. Temp work is expected to continue growing through 2014.

None of these trends are new: The disappearance of good middle-class and blue-collar jobs began well before the recession. But the recession has magnified the impact, reducing hiring and turnover rates.

It’s particularly concerning given that the short-term unemployed also tend to be younger: 57% are between the ages of 16 and 34 years old, according to the Princeton paper. Those early years in the labor force are critical to determining the future earnings and career paths, and it takes a long time to overcome setbacks, notes Lawrence Katz, an economics professor at Harvard University.

“About 30 to 40% wage growth happens in the first five or six years,” Katz says. If young adults aren’t working to their full potential, he adds, “that’s a lot of wasted mobility.”

The scars of unemployment become deeper the more time passes. But they’re still likely to be there for those who’ve been unemployed for any length of time whatsoever—it’s simply a matter of degree.

Those who were previously unemployed for less than 6 months will earn 24% less, while wages drop 67% for those who had long spells of unemployment, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston have found.