In the 7 months since Russian President Vladimir Putin signed into law a series of restrictions on the country’s LGBT population, activists have held meetings, staged protests, organized festivals, and strategized about how to take advantage of the world’s attention during the Sochi Olympics.

Turns out, they won’t be doing much during the Games after all.

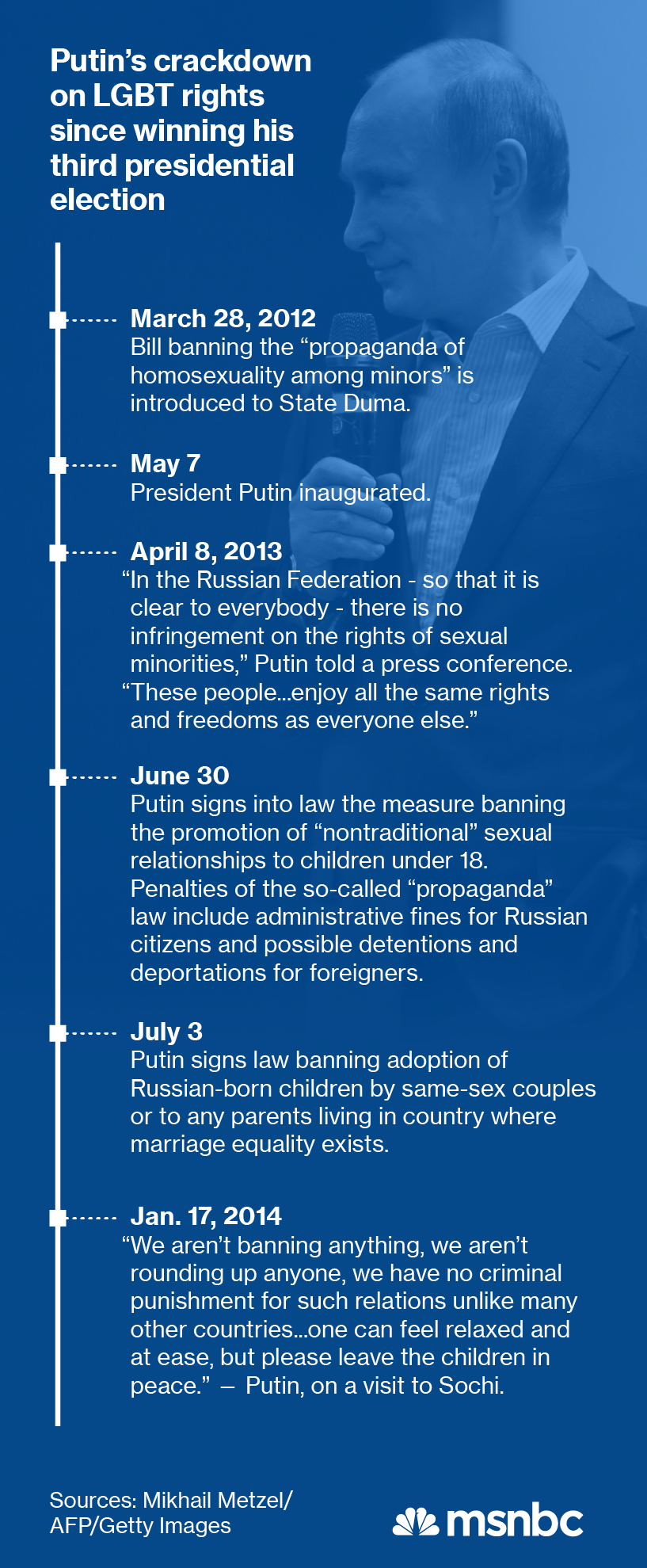

Despite widely publicized outrage over Russia’s anti-gay laws — one in particular banning the promotion of “nontraditional” sexual relationships among minors — the 2014 Winter Games will be surprisingly devoid of LGBT activism.

Sure, there still could be a watershed moment for gay rights on the podium–à la Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ history-making salute at the 1968 Games–or a lone demonstrator waving a rainbow flag, as happened recently in the city of Voronezh, 560 miles north of Sochi, during the Olympic torch relay.

But as for organized demonstrations at the Games themselves, Russian activists say they’re not likely.

“In all honesty, it’s probably not a good idea to have real protests at the Games,” Anastasia Smirnova, coordinator of the Russian LGBT Network, told msnbc. “It might not be the right place for that. But we hope for individuals to make their own statements in support of equality and human dignity…wearing a T-shirt, things like that.”

Under the so-called “propaganda” law, any Russian citizen who promotes information about homosexual relationships to children could be subject to administrative fines, while any foreigner who does so could face detention or possible deportation. So far, very few people have been prosecuted under the law’s vaguely-worded terms, and LGBT advocates are largely unconcerned of any prosecutions during the Olympics, when the whole is watching.

“It’s probably going to be the safest time,” said Polina Andrianova of the St. Petersburg-based group, Coming Out. “I don’t think our authorities want to continue the international scandal.”

The biggest hindrance to any protest at the Games, however, stems from escalating terror threats. Following recent suicide bombings in the neighboring city of Volgograd, Putin responded by deploying close to 60,000 police officers, troops, and special forces to Sochi — twice the number Britain enlisted in London for the 2012 summer Games. With that level of security, activists say, any planned demonstration would likely be impossible.

“Anyone who is going to be present in the greater Sochi area related to human rights should be prepared for increased attention from the authorities, and from the police who will be overlooking anyone doing anything in the region,” said Smirnova, the only LGBT activist interviewed who plans on attending the Games. “I was recommended by my colleagues to be very attentive, to take care of myself, and to be prepared for a lot of attention toward my plans.”

The absence of activism should in no way suggest that advocates are giving up or discarding month of hardships, including government retaliation and vigilante violence. Rather, while most people look with anticipation toward Feb. 7, the Games’ opening ceremony, activists have become far more focused on Feb. 23–the day they end.

“There is a lot of fear the situation is going to degrade after the Olympics are over,” said Andrianova. “That will be the most vulnerable time.”

Under pressure to rein in his harsh policies–or at least look like he is– Putin has recently made several attempts to soften his government’s image around human rights and LGBT issues in particular. Last month, Putin released jailed Kremlin critics–businessman Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the punk rock group Pussy Riot–in a high-profile amnesty approval. Before that, Putin dropped piracy charges against 30 Greenpeace activists, replacing them with lesser hooliganism charges for trying to scale an offshore oil platform. He also lifted a blanket ban on protests at Sochi, though plans to keep them restricted to a designated zone, largely removed from the Games’ events.

And in the latest gesture, Putin declared three weeks before the Olympics that gay visitors should feel “relaxed and at ease,” while requesting that they keep in line with the propaganda law and “leave the children in peace.”

Activists worry, however, that those moves were nothing more than a PR stunt designed to keep criticism at bay and generate enthusiasm for the Olympics, on which Putin has staked his presidential legacy.

Signs of a potential reversal after the Games have already begun to surface. Last week, Konstantin Dolgov, the Russian foreign ministry’s human rights commissioner, presented a 153-page report in Brussels attacking the European Union for trying to push “an alien view” of homosexuality onto other countries.

“I am sometimes afraid,” confessed 20-year-old Daniil Grachev, who has had several run-ins with the law since joining the ranks of Russia’s small but determined LGBT advocacy movement. Grachev was most recently arrested during an October rally in St. Petersburg to mark National Coming Out Day, along with 67 others. Initially, he said, police did nothing to protect them, even after anti-gay campaigners began to attack.

“It’s not like in other countries, where the police will protect you,” said Grachev. “You have to make the whole government stop hating you and blaming you for everything.”