CHICAGO — Each time Randy Nowak was locked up, it was because of his heroin habit: He’d steal whatever he could grab from Home Depot, Menards, or Lowe’s to pay for his next fix.

But Nowak, 31, doesn’t think he’ll be going back to jail again. He’s now farther along in drug treatment than he’s ever been before, covered by the Obamacare that he signed up for the last time he was in Cook County Jail.

“I was able to go into a hospital with proper care, it wasn’t some clinic — it was just more professional,” said Nowak, who recently made it past detox for the first time, then completed a month of intensive drug treatment. Insured through Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion, he’s now in a community integration program at Haymarket Center and plans to go back to college this year, having dropped out more than a decade earlier when he first became addicted to heroin.

Nowak is among the 10,000 people who’ve gotten health coverage as a result of applications that got started in Cook County Jail — the largest single-site jail in the country. “We believe a majority of individuals who start applications at the jail are able to enroll due to Medicaid expansion, based on the population the jail serves,” said Alexandra Normington, a spokesperson for the Cook County Health & Hospitals System.

Chicago was one of the first places in the country to enroll individuals in Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion through the criminal justice system, as Illinois got permission from the Obama administration to expand the program early in Cook County. Similar programs to enroll inmates have also sprung up in California, Oregon, Colorado, Minnesota, Connecticut, Utah, New Jersey, Maryland, and Kentucky, according to the National Association of Counties.

Officials supporting these programs anticipate that inmates will continue to receive the treatment they need after they leave jail, which remains a vital source of health care for a population that’s largely uninsured. Inmates cannot complete their enrollment or receive coverage until after they’re released, but they can begin the process of signing up while they’re incarcerated.

Jails are a particularly effective way to connect with individuals who qualify for the Medicaid expansion, which covers those earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level, or $16,243 for a single adult. The Justice Department estimated in 2011 that at least 35% of those eligible for the Medicaid expansion — were it implemented in every state — would have “a history of criminal justice system involvement.”

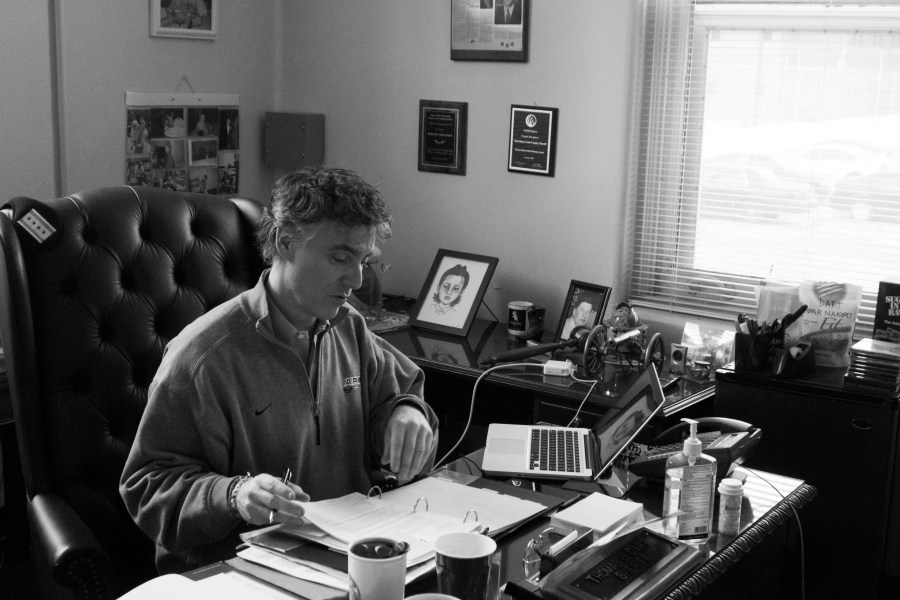

Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart is particularly hopeful about the impact of health coverage on mental and behavioral health: His office estimates that roughly one-third of the jail’s inmates are mentally ill, and the “vast majority” are dealing with substance abuse.

“We do all this work with them while they’re here, we identify different issues with them while they’re here. Then we’re sending them out the door with literally a plastic baggie full of pills,” said Dart, who describes his jail as the largest mental health provider in the state.

%22I%20have%20the%20highest%20level%20of%20confidence%20that%20this%20will%20either%20keep%20them%20from%20coming%20back%2C%20or%20extend%20out%20the%20period%20of%20time%20before%20they%20come%20back.%22′

Though Dart says it’s too early to see the impact on recidivism rates, he believes that the coverage expansion will ultimately make Chicagoans less likely to commit the crimes that lead many of them to his custody. “I have the highest level of confidence that this will either keep them from coming back, or extend out the period of time before they come back,” he said.

Treatment beyond the ER and jail

Those supporting the enrollment effort in jails argue that it will also alleviate the fiscal burden on county and state governments that help cover the cost of uncompensated care.

Before she got coverage, Katherine Rodgers, 49, would routinely wait for more than 11 hours at Cook County Hospital to get medication for her thyroid condition, diabetes, high blood pressure, and bipolar disorder. But she endured the wait because she couldn’t afford to pay for her meds on her own. Ultimately, the county government would help cover the cost of caring for uninsured patients like Rodgers.

Illinois’ jails and prisons serve as another de facto safety net for the poor and uninsured. Rodgers was diagnosed and treated for thyroid cancer when she was locked up in 2005 and started receiving medication for her mental illness in 2011. “If I didn’t go to prison, I would probably be dead today or I probably wouldn’t be able to talk,” she said of her cancer diagnosis.

Things started to change for Rodgers last year when she connected with Thresholds, a mental-health service provider, right after being released on bond for a drug possession charge. Thresholds has not only provided her with mental health care, but also helped her with insurance enrollment. This month, she’ll start receiving CountyCare, the Medicaid plan run by the Cook County Health and Hospitals System that Illinois got permission to expand early.

“If I stay on my medication, things will get better for me,” said Rodgers. She’s also excited about the prospect of having coverage for other basic services, having extracted her own teeth with pliers on multiple occasions because she couldn’t afford a dentist.

There’s an upside for some providers as well. Thresholds can only afford to see a limited number of uninsured patients because their costs have to be covered by private donations, according to Peggy Flaherty, vice president of clinical operations at the organization. The expansion has now broadened the pool of patients that Thresholds can serve.

Haymarket Center, for its part, had relied on state and federal funds to pay for uninsured patients — a relationship that was also fiscally precarious. “The problem with that system is because of the state’s financial woes, it was consistently cut,” said Jeffrey Collord, Haymarket’s director of development and external affairs. “Moving clients into some kind of insurance coverage ought to stabilize the funding.”

Obstacles and controversy

There was early resistance to the enrollment initiative in Chicago, some of it coming from the inmates themselves. “There was a lot of skepticism when the program first came on up — ‘the sheriffs are trying to trick us, they’re trying to get more information,’” said Sergeant Wilfredo Cintron, who works at the jail. “But once they found out, and they saw it was actually benefiting them and their family, they’re giving actual real information.”

Starting the enrollment process, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that individuals will receive care when they leave.

%22If%20I%20didn%27t%20go%20to%20prison%2C%20I%20would%20probably%20be%20dead%20today%20or%20I%20probably%20wouldn%27t%20be%20able%20to%20talk.%22′

At Cook County Jail, caseworkers for Treatment Alternative for Safe Communities (TASC) try to start them off on the right foot. The enrollment process begins from the moment they’re processed into the jail: After they get their photos and fingerprints taken, go through the metal detectors, and give up their street clothes for beige jumpsuits, they sit down to have a one-on-one session with a TASC staff member to see if they’re qualified for Obamacare.