Despite a surge of panic about Ebola in the United States, health experts believe the single most effective way to combat the disease is to focus America’s attention on West Africa. But leading aid groups warn that staffing shortfalls, logistical challenges and other bottlenecks could undermine efforts by the U.S and its partners to fight the virus overseas.

The U.S. has devoted more resources than any other nation to fighting Ebola, committing more than $350 million in aid to the region. The U.S. government has also pledged to send up to 4,000 troops to the area to build Ebola treatment centers in Liberia, the country hit hardest by the outbreak.

RELATED: More travel restrictions announced as Ebola ‘czar’ starts

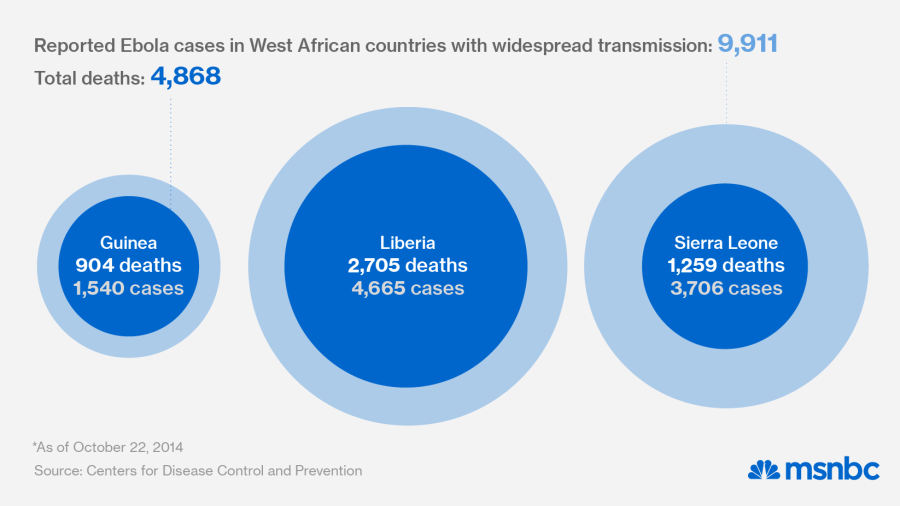

Ebola has crippled West Africa’s already fragile health care system, increasing the urgency for outside assistance. Nearly 100 health care workers have died of Ebola in Liberia, according to the World Health Organization. Overall, the WHO says there have been 9,900 Ebola cases and 4,900 deaths to date, though the group acknowledges that the actual number is likely much higher because of under-reporting.

%22The%20fire%20is%20burning%20out%20of%20control.%22′

Concerns about the Ebola response in West Africa go beyond finances. “It’s not just money—it’s how to mobilize what is available as quickly as possible. The fire is burning out of control,” said Jennifer Kates, director of global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Sophie Delaunay, executive director of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in the United States, praised the U.S. government for the scale of its response in West Africa. But Delaunay is concerned that staffing shortages could hamper the containment efforts.

RELATED: Ebola continues its deadly march

The U.S., for example, has committed its troops to building 17 Ebola treatment units with 100 beds each in Liberia. But neither the U.S. Department of Defense nor U.S. government health workers will be directly managing or running them.

“The U.S. did not have a willingness to have the [Department of Defense] run these facilities, which for us is a matter of concern. They want to identify the NGO (non-governmental organization) and other partners to take care of these aspects. But we believe it will be impossible for them to find these sufficiently skilled staff,” said Delaunay, whose group has been leading the fight against Ebola in West Africa.

“We really need to convince the U.S. government to take a greater part in the management and running of these centers,” she added.

Given the politics surrounding Ebola in the U.S.—and the concern about endangering U.S. troops—it’s an unlikely outcome. Before approving funding for the mission, U.S. lawmakers demanded that the Obama administration provide assurances that the health of American troops would be protected.

“As a few thousand of our troops will be sent into harm’s way, I am deeply committed to continuing to conduct rigorous oversight of this mission to ensure our men and women are provided the protection they deserve,” Oklahoma Republican Sen. James Inhofe said Oct. 10. The White House originally requested $1 billion for the operation, but Congress chose to approve $750 million instead, as lawmakers like Inhofe said the administration did not have a sufficient plan for transitioning out of the region.

Officials from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) say that the Liberian government, with assistance from the WHO and countries like the U.S., will take the lead in finding staff. “We are confident, working in support of the government of Liberia, that all planned ETUs (Ebola treatment units) will be staffed appropriately with medical professionals, trained health workers and support staff,” said Matthew Herrick, spokesman for USAID, who estimated that “anywhere between 80-90% will be sourced locally.”

“There are lot of people in Liberia willing to work and just need to be trained,” Bill Berger, who leads the U.S. government’s Ebola response team in West Africa, said in a phone interview from Liberia. While the U.S. military won’t be directly staffing the units, it will train local residents to work in them. Berger believes such efforts will help Liberia become more self-reliant in the long term as well, “so they can fight Ebola if there’s an outbreak in the future.”

The need for adequate staff is critical: A single 100-bed treatment center needs 200 staff and costs about $1.1 million to run, according to Rebecca Milner of the International Medical Corps, another aid group working in the region. Just putting on, taking off and disposing of the personal protective equipment is labor-intensive, and each suit can only be worn for an hour or two at a time, given the region’s climate, she explained.

%22There%20is%20concern%20with%20the%20fact%20that%20because%20the%20deployment%20is%20slow%2C%20the%20outbreak%20is%20actually%20ahead%20of%20us.%22′

The entire West Africa region will need 19,000 additional doctors, nurses and paramedics by Dec. 1 to fight the epidemic. But convincing others to come help has been a serious challenge, said Delaunay. “It’s not easy to find human resources in this context. It’s scary—there is a lot of stigma around Ebola.” USAID is appealing for qualified health workers to volunteer in West Africa through its website.

There have also been delays in opening a 25-bed hospital for health care workers in Liberia, which the U.S. government is also constructing. Officials hope the hospital will help encourage more aid workers to help on the front lines of the epidemic, particularly as the facility will be staffed by 65 officers from the U.S. government’s public health service commissioned corps. But the hospital’s opening has now been pushed back from mid-October to early November. The first ten Ebola treatment units will be rolled out between mid-November and mid-December—also later than originally expected.

The delays have frustrated some working to combat the epidemic on the ground. “I am not criticizing the military, not criticizing the president, but what I’m saying is the hospital isn’t working yet,” said Ken Isaacs of Samaritan’s Purse, a Christian aid organization whose medical director, Dr. Kent Brantley, is an Ebola survivor who contracted the disease while working in Liberia.

Isaacs was in Liberia helping to deliver supplies two weeks ago, when he said there was still a lack of transportation and logistical support on the ground.

The epidemic has continued to defy predictions about the scale of the response necessary in West Africa, which has made rapid mobilization even more urgent, said Delaunay of Doctors Without Borders.

“There is concern with the fact that because the deployment is slow, the outbreak is actually ahead of us,” she said. “The amount of beds, treatments needs are higher than what we had estimated at the time and what has been committed.”

Among other things, Isaacs wishes that American troops would arrive more quickly. Currently, 617 U.S. military personnel are in the country, in addition to 171 civilian staff.