What’s causing those mysteriously bright spots to shine inside a crater on the dwarf planet Ceres? Does a layer of ice that was once an ocean lie just beneath the surface? And was there ever life on Ceres?

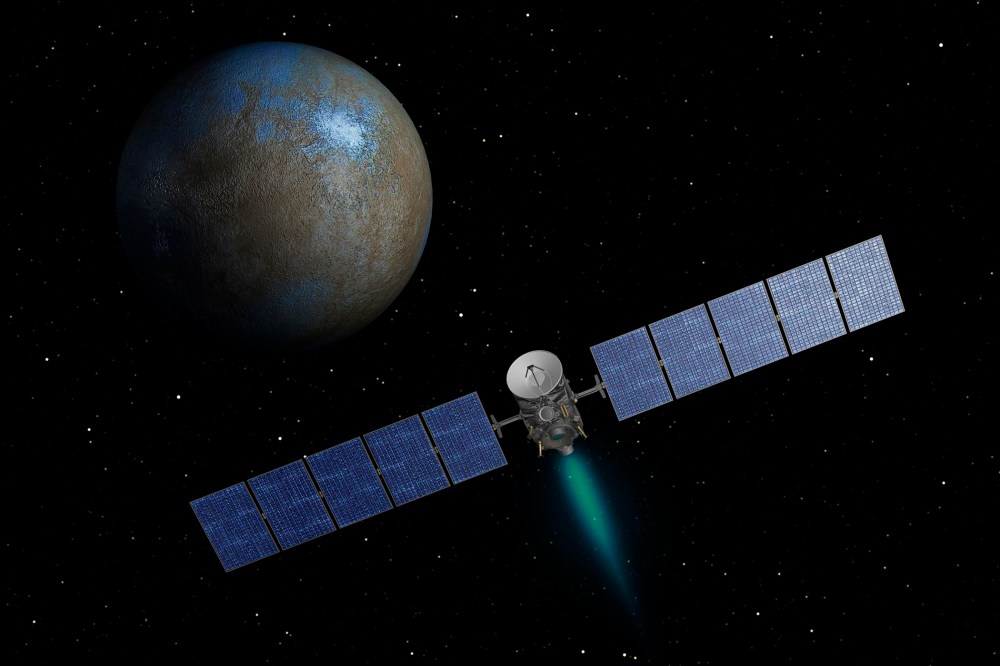

Those questions are on the verge of being addressed, thanks to Friday’s scheduled arrival of NASA’s Dawn spacecraft into Cereian orbit at the climax of a $473 million mission. Just don’t expect the answers to come immediately.

After snapping months’ worth of sunlit pictures of the solar system’s largest asteroid and the smallest known dwarf planet, Dawn has switched over to the dark side for its entry into orbit, Dawn project manager Robert Mase said Monday during a news briefing at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“We’re going to have a blackout for the next month, until we get back over toward the lit side. But then the floodgates are really going to open when we get to our first science orbit in late April,” Mase said.

Friday will mark the first time that the same NASA probe has gone into orbit around two celestial bodies beyond Earth, said Jim Green, director of NASA Headquarters’ Planetary Science Division. After Dawn’s launch in 2007, the science team spent the mission’s first five years focusing on the asteroid Vesta. The refrigerator-sized, ion-driven spacecraft moved out of orbit around Vesta in 2012and headed for 590-mile-wide (950-kilometer-wide) Ceres — which is so big and round that it’s classified as a dwarf planet, like Pluto.

Although they share a planetary pigeonhole, Ceres isn’t anything like Pluto, said Dawn’s deputy principal investigator, Carol Raymond. Pluto is thought to have a rocky core and an icy shell, but Ceres is more complex. It probably had a subsurface ocean of liquid water at some point, Raymond said. Scientists believe that ocean has now frozen into solid ice, covered by a crust of rock, dust and debris.

Mysteries await

At some point in its 4.5 billion-year history, Ceres could have fostered life: “We do expect that it had astrobiological potential,” Raymond said. Last year, scientists reported that the European Space Agency’s Herschel telescope had detected emissions of water vapor from Ceres, and Dawn will be in a position to follow up on those mysterious findings.

Dawn has an even bigger mystery to deal with: Before the current blackout, the probe took pictures of two unexpectedly bright spots paired up on the surface. “Suffice it to say that these spots were extremely surprising to the team,” Raymond said.

She said those spots could be related to the water vapor emissions. They might be bright patches of ice or salt-rich material that’s been exposed at the bottom of an impact crater. There’s a chance they could be created by ice volcanoes, although Raymond said that’s unlikely because they don’t appear to have built themselves up above the surface.

The brightness is apparently due to reflected sunlight, which fades away as night falls on Ceres. “The spots do get darker and then go out when the terminator is reached,” UCLA astronomer Chris Russell, the principal investigator for the Dawn mission, said Monday.