In 1981, a young lawyer in President Ronald Reagan’s Justice Department wrote a memo to his boss.

Congress was working on reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act, and was considering strengthening a key provision, known as Section 2, to make clear that it barred not only intentional racial discrimination in voting, but also actions with clear discriminatory results—that is, that disproportionately hurt racial minorities.

The lawyer staunchly opposed the move, which Congress ended up adopting. Defining discrimination more broadly, he warned Attorney General William French Smith, would “provide a basis for the most intrusive interference imaginable by federal courts into state and local processes,” and “would raise grave constitutional questions.”

That young lawyer was John Roberts, today the chief justice of the Supreme Court. Last month, Roberts wrote the opinion in the ruling invalidating Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act in its current form, the culmination of years of conservative advocacy. Now, voting rights supporters fear a determined push by the right could let the Roberts Court go after the landmark civil right’s law’s other key pillar, Section 2.

“Section 2 is a ripe target,” Christopher Elmendorf, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, who has written in depth on the provision, told msnbc.

If the court were to strike down or substantially weaken Section 2, the Voting Rights Act would technically still exist, and would retain a few historically important functions—its ban on poll taxes and literacy tests, for instance. But, on top of the demise of Section 5, the most successful civil rights law in the nation’s history would be all but a dead letter.

“There’s no question that Section 2 and 5 together are really the heart of the law,” Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School, who testified at Wednesday’s Senate hearing on fixing the Voting Rights Act, told msnbc.

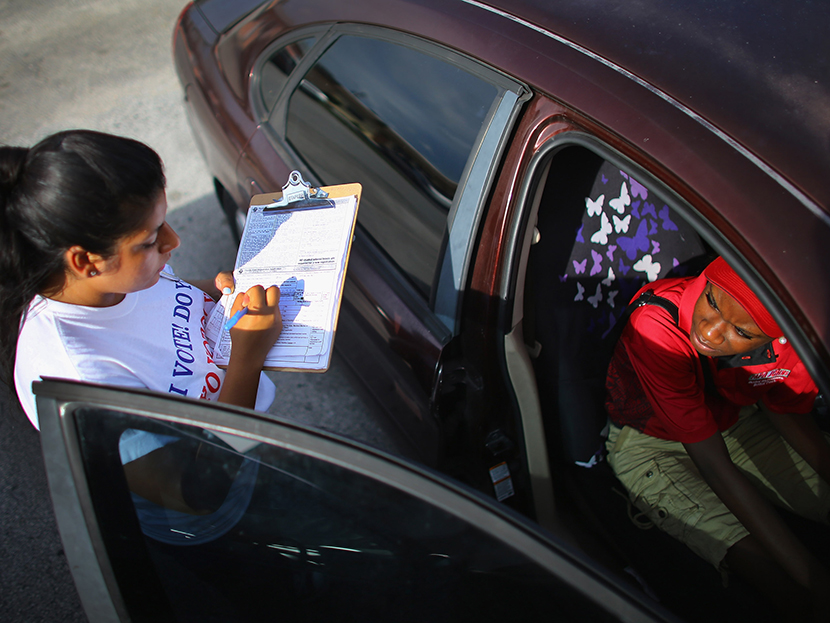

Unlike Section 5, Section 2—which lets victims of racial discrimination file suit—is an after-the-fact remedy, making it a less effective tool for stopping race bias in voting. Still, it’s the strongest protection that the Voting Rights Act has left, and the weeks since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shelby County v. Holder have made clear that Section 2 now figures to play a crucial role in legal efforts to defend voting rights, including in cases against voter ID, cutbacks to early voting, and other Republican-backed voting restrictions.

Days after the decision came down, opponents of Texas’ voter ID law, who last year succeeded in blocking the measure under Section 5, filed a new lawsuit under Section 2. And Attorney General Eric Holder announced Tuesday that in Section 5’s absence, the Justice Department would shift resources toward Section 2 cases.

Related: House GOP’s half-hearted first attempt to patch Voting Rights Act

The argument against Section 2 is that by banning actions with discriminatory results, not just intent, it goes beyond what the Constitution empowers Congress to do. The 14th and 15thAmendments explicitly ban only intentional discrimination.

Election lawyers say it’s unlikely that even the Roberts Court would fully sign onto that view and strike down Section 2 on its face. Much more plausible is that the justices could progressively narrow it by requiring more evidence that intentional discrimination played a role in the action being challenged.

Already, voting lawyers say, Section 2 is almost never used without some evidence of an intent to discriminate—a local history of discrimination, for instance, or race-based appeals by candidates in an election. That’s why efforts to use Section 2 to bar state laws that disenfranchise felons—which inarguably hurt racial minorities more than whites—haven’t succeeded. And, said William Baude, a professor at Stanford Law School and a former Roberts clerk, it’s one reason to think that Section 2 also will fail to stop voter ID laws like Texas’.

But a concerted effort by conservatives could lead to that threshold for evidence of intent being significantly raised—ultimately making Section 2 useless for stopping any but the most blatant acts of racial bias.

“One can pursue an agenda of sort of rolling back Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act substantially, without ever having to declare it unconstitutional,” Elmendorf said.

Advocates on both sides of the voting-rights debate are typically cagey about future strategy, not wanting to limit their options or give their opponents a window into their plans. But there are some signs that a stealth assault on Section 2 could soon emerge.